Haroon Moghul’s new memoir weaves atheism, divorce, interfaith politics, and bipolar disorder into a story that is, as the title affirms, utterly American. And a riveting read.

RD: What inspired you to write How to Be a Muslim: An American Story?

Haroon Moghul: Officially, this book began, in very, very different form, when a contact at a major university press asked me to write a textbook about Islam in America. I could not believe my good fortune. I’d taken summer classes at Yale, and still got turned down when it came to college. Fail. But here I was, a Yale reject, about to have Yale publish my book!

The irony was delicious. Maybe too tasty. Yale rejected the final product, contending it was a memoir trying to pass itself off as an academic monograph. Double fail. Sadly I agreed, and went to watch I, Frankenstein for consolation. Then I was more depressed, because it was like someone paid money to make that movie, but no one will publish my memoir?

I went back to the drawing board with Beacon Press, and re-wrote the whole thing. I realized I didn’t want to write an academic monograph, and that academic writing was too limiting. The topic was too important to be decipherable by five people, one of whom was my thesis advisor.

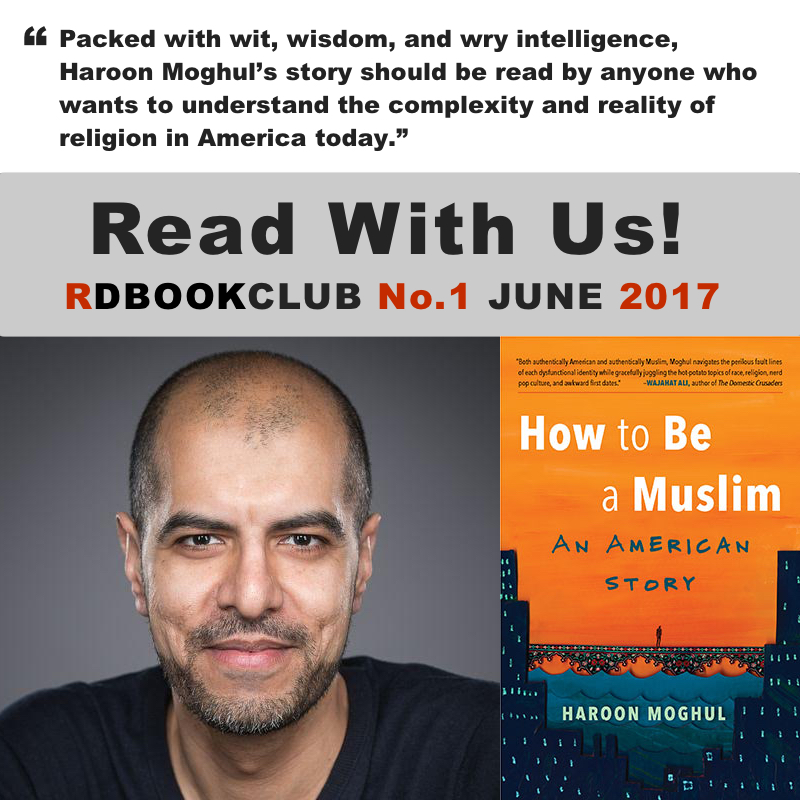

How to Be a Muslim: An American Story

Haroon Moghul

Beacon Press

June 2017

Unofficially, this book began with two short stories I was asked to contribute to two different collections. The first essay was a short story about how I became an atheist. The second story was about how I snuck out to prom, and kissed a girl in the process. More than once. At the time I was so terrified of the American Muslim echo chamber that I was sure I’d be excommunicated. Five or ten years ago, those topics might’ve been taboo. Instead my stories were embraced, and I realized I had a story to tell, Yale press or no press. Or, rather, another press. But I digress.

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

That Muslims can be funny. And people. Because we are people. Amazingly. And it is really cool to sneak out to prom, unless you get dumped the next day. I’m still not quite over that.

Is there anything you had to leave out?

I ended the book in 2013, which means I didn’t get to tell the story of my work with the Shalom Hartman Institute, where I’m now the Fellow in Muslim-Jewish Relations. I wish I could have told the story of what it was like to be in New York during the so-called Ground Zero Mosque controversy.

At the end of How to be a Muslim, I’ve just gotten married, but I didn’t get to talk about that journey, about what it was like to fall in love again, or even just what it’s like to find your footing after a major failure, and how differently I look at the world today. If this book is about how I learned to find an Islam for myself, the next one would be what I think an Islam for the future could look like.

Because while some Muslims are interested in the past, I’m interested in crafting an Islam through which we make sense of our lives, anticipate the future, and bend it to a moral conscience.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

American Muslims—how could there possibly be any misconceptions? (Sarcasm.) I once read a poll that indicated that whether an American thought Obama was a Muslim was the single greatest predictor of whether she voted for Clinton or Trump. It’s flattering to represent a demented national obsession, but it’s also deeply disturbing. Yes, ISIS is dangerous and, true, Muhammad Ali meant a lot to America, but we exaggerate the role and influence of Islam in the world, at great cost. We’re ignoring income inequality, the failure of our education system—what else explains our inability to have a meaningful national conversation about anything from gender to science—climate change, Russia, China, and a thousand other things beside, just because of some admittedly very dangerous but equally not very sophisticated terrorists.

Or, like someone said to me after one of my book readings, “I thought you were going to be Hamas.” Seriously?

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing?

My life kind of crashed and burned when I hit 32. Outwardly, everything was going great. I was flying high. I had a great job, a beautiful wife, a fantastic apartment, a solid upper middle class salary, and a glowing reputation as a rising American Muslim leader. After a fundraising dinner, someone called me the Muslim Obama. I countered that Obama was the Muslim Obama. He snorted chai out his nose.

On the inside, though, I was dying. I was horribly sick, deeply depressed, my marriage was struggling, and I didn’t even know if I wanted to be Muslim, let alone a leader. I ended up inpatient psychiatric for a few days, and later almost killed myself. I struggled for months more with suicidal ideation. I kind of still do. It sucks.

But I haven’t given in to that impulse in part because I wrote this book. Right in the middle of all of that, a therapist told me that I’d never overcome my crippling bipolar disorder if I didn’t figure out what I loved about myself. (To be clear, she also insisted on therapy and medication.) At the time, I could not only not think of what I loved about myself, but I thought the question inappropriate. What a load of self-centered, entitled bullshit. But she said, “Write it down when you find out.” I wrote this book instead. You know what I found out? That when the voices drag me to the edge of a bridge, make me contemplate ending myself, writing saves me.

I’ve four more books I want to write, three of which I describe below. So I have to live for them. Of course, what happens if and when I finish—insh’allah—is another story. One battle at a time.

Are you hoping to just inform readers? Entertain them? Piss them off?

There are a thousand books, probably, about Islamophobia and terrorism. I didn’t want to write that book. Yes, national security and foreign policy inform my life journey, but this is a very human story about falling in love, about trying and failing to find yourself, about mental illness, about how travel restores and redefines us and, ultimately, what it is like when your life doesn’t turn out the way you thought it would, about what it’s like to fall to pieces, and whether you can ever put yourself back together again.

The particulars of my journey are framed through Islam, yeah, but also through being the child of immigrants, growing up in New England, going to school in New York. The specifics are different for each person, but any person can find something of herself in this story, and that’s why I wrote this. To say we aren’t that different after all.

What alternative title would you give the book?

How To Be A Human: A Muslim Story.

How do you feel about the cover?

I love it. It took a few tries to get there, but I’m really happy with it. I would like to tell you that it’s orange in honor of our President, but I don’t think that’s the original motivation. What’s odder still is that my previous book, a novel, The Order of Light, also has an orange cover. Apparently if I had a flavor, it would be citrus.

Is there a book out there you wish you had written? Which one? Why?

The Lord of the Rings, not least because, if I wrote it, I would be able to write more books about Middle Earth and then I’d finally know what happened to, say, the Avari. I get that it’s about the origins of modern Europe, but why does the East have to be such a malicious place?

What’s your next book?

I’m working on three novels, a proper trilogy, that I can best describe as a cross between science fiction, Bollywood, and alternative history. The first, Americans, takes place in the 21st and 17th centuries, and tells the story of two best friends who get stranded outside each other’s timelines and try to find their way back, even as each move they make changes the world the other one lives in. It basically asks what happens if people from now get stuck in the past, and what they’d end up doing to the future.

The second, Indians, takes place in the 23rd century, and starts with a simple conceit—would you end up a generation of wandering, in a sidereal desert as it were, if the only place you found capable of supporting life lived in permanent night?

And the third, Humans, takes place another three thousand years after that. All these stories are connected, and go back to the decisions made by these two friends, Mujib and Ali, and the families they found. I take inspiration from Muslim, South Asian, Dutch, Spanish, French and American history to create an entirely new universe. There’s alien Caliphs and medieval monarchies that never end, stretching far into the future, colonizing other worlds and inventing entirely new conceptions of what it means to be a human. Give me ten years.