In The Name of God Is Mercy , Pope Francis’ new book, the pontiff does more riffing than writing. The book is based on a series of interviews he gave to Vatican journalist Andrea Tornielli, and it showcases his famous tendency to go off script with the press. Francis’ famous quote about gay priests—“Who am I to judge?”—occurred on a trip from Brazil to Italy, and footage from Vatican press events often shows him joking around with journalists.

Francis may be the first modern pope who actually likes talking to the press.

Considering the image overhaul he’s trying to bring about for the church he leads, a cynic might be tempted to say this kind of relationship is strategic. In The Name of God Is Mercy, Francis comes across as warm, avuncular and compassionate, qualities journalists who’ve interviewed him echo in their own stories from the press corps.

Francis tells Tornielli that he prefers to think of mercy as an active process: “I like to translate miserando with a gerund that doesn’t exist: mercyifying.” He reiterates the image of the church as a field hospital where “treatment is given above all to those who are most wounded,” and many of his reoccurring anecdotes about mercy have to do with prisons and prisoners. “I have a special relationship with people in prisons,” Francis says, “precisely because of my awareness of being a sinner.” The pope sees imprisonment as a matter of convenience for many nations who prefer to condemn people rather than offer them opportunities: “Sometimes we prefer to shut a person in prison for his whole life rather than trying to rehabilitate him and helping him find his place in society.”

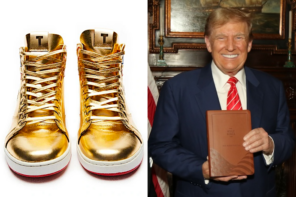

For all his talk of sinfulness, however, Francis’ vision of the church is of one that is actively forgiving. “The church does not exist to condemn people but to bring about an encounter with the visceral love of God’s mercy,” he tells Tornielli, and in order for that to happen, it must “go outside and look for people where they live, where they suffer, and where they hope.” But is that possible in societies like America, where wealth and success dominate our imagination of a good life? When the pope sounds pessimistic, it is often in statements like this: “Corruption is not an act but a condition, a personal and social state in which we become accustomed to living.” In this particular moment of American political ugliness being displayed in the presidential debates, that corruption seems insurmountable.

What will American readers make of this message? Mercy is not something we discuss very often. Our rates of incarceration, the number of states utilizing the death penalty, our obsessive clinging to the Second Amendment along with its deadly consequences, ICE raids on immigrant families fleeing even worse violence in their home countries, drone strikes, the environmental violence of fracking, deforestation and coal mining, and the daily threats faced by women, LGBTQ people and people of color are all evidence that we are hardly a merciful nation. We were built, after all, as the result of a protracted war, and we grew in power on the backs of slaves.

American religious history, too, is fraught with prejudice and bias—even against Catholics, with “popery” having been perceived as highly suspect for many decades. But American Catholicism has from the beginning been shaped by immigrants, and resists a narrow, singular identity in the manner of WASPs. Beyond that, Francis’ vision of the confessional as a place of mercy is not the experience of many American Catholics. Francis tells Tonelli that when he regularly took confessions, “I always thought about myself, about my own sins, about my need for mercy, and so I tried to forgive a great deal.” This is a humbling image of a priest who sees himself as equally sinful to the penitent. But only 2 percent of American Catholics go to confession regularly. Three-quarters of them only go once a year, if ever.

Mercy is depicted in our media not as divine intervention, but as human instinct.

After the Catholic Church published Humanae Vitae in 1968, the Vatican’s disapproval of birth control meant that the vast majority of Catholics who used it—and continue to use it—no longer felt the church was an authority on sexual matters. This relationship with the confessional was further eroded in the wake of the sex abuse scandal, when the secrecy of the confessional became a convenient cover for the molestation of children and young adults.

Jesus never intended for mercy and forgiveness to be something given only by church authorities: During Mass, the congregation confesses to one another en masse during the Confiteor. Priests, bishops and popes did not even exist in Jesus’ imagination. Confession has become a public act, a regular feature of social media, the basis for television interviews, books, essays, blogs. These can be awkward and painful to witness, but they offer some sense of participatory release. We are no longer forgiven by God, but by one another.

The majority of Americans do not get their ideas about mercy from churches. They get it from television and films. And in our entertainment, mercy is not something given by God, but given from one person to another. In the new Star Wars film, Finn’s merciful act toward the imprisoned Poe ends up liberating both of them. On Jane the Virgin, the mercy given from parents to children is a reoccurring theme. Even in the recent film Spotlight, it is not the archdiocese of Boston or the priests who molested children who offer mercy to the victims. It’s the reporters who broke the story and got to know them as individuals who offer reconciliation and healing. Mercy is depicted in our media not as divine intervention, but as human instinct.

Moral theologian Thomas Massaro, S.J., told RD that American Catholics “rarely think deeply about mercy at all, much less in the refined ways the pope is articulating.” Massaro adds that part of this stems from the fact that Americans do not see mercy as “a virtue that needs to be practiced to be habituated,” but that American Catholics’ mercy mirrors the “Practice Random Acts of Kindness” bumper sticker more than Francis’ calling to “incorporate an attitude of mercy into daily life.” Massaro adds that American Catholics are generally full of good intentions, but often at a loss for ways to “regularize this into a commitment and priority.”

The American Catholic church, too, is far less homogeneous than the Argentinian church from which Francis’ ideas about mercy evolved. Argentina may be one of South America’s more politically progressive countries, but it remains an overwhelmingly Catholic country with a dominant Spanish influence. With a dizzying number of languages, economic classes, ethnicities and cultures represented in American Catholic churches, American Catholics resist singularity. And it follows that they are going to be inconsistent in how they define mercy, as the hierarchy of the American church is often wont to demonstrate.

Even the variety of American “Mercy Doors” found online defies comparison to the huge, ornately carved bass doors Francis pushed open at St. Peter’s when he declared the beginning of the Year of Mercy. Every diocese and significant shrine is eligible to have a special door during the Year of Mercy, and when pilgrims pass through it, they’re granted an indulgence—time off in Purgatory.

Unlike the stately and magnificent Vatican door, the American Mercy doors demonstrated a wild range of architecture, from glass sliding doors like those of a shopping mall, to scuffed wooden doors, to the one church that didn’t have a special door, so they built a frame in a garden. Those doors mirror the incoherent diversity of the American church, and its mixed relationship with the idea of mercy.

The most powerful example of American mercy in recent memory did not come from a religious leader. It came from the families of the victims of the Charleston shooting, who forgave Dylann Roof, the killer who had sat in on their Bible study before massacring them. They asked, several times, for God to have mercy on Roof. But Roof will likely die by lethal injection since South Carolina has one of the highest rates of executions in the United States. And lethal injection is considered a more merciful form of execution than our older methods of hanging, firing squad or guillotine.

That is the puzzle of American mercy that Pope Francis will never be able to solve, as much as many would like him to: Our mercy can be given, but so easily taken away.