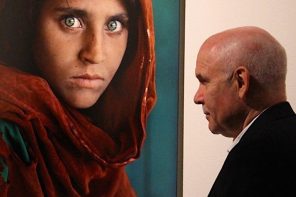

A month ago ten humanitarian aid workers in Afghanistan, most of them apparently called to medical mission by a deep Christian faith, were massacred by the Taliban. The New York Times’ front-page caption beneath their pictures read: “Humanitarian Victims of Afghan Violence.” The story began: “Their devotion was perhaps most evident in what they gave up to carry out their mission.” My question: should we not be calling them Christian martyrs?

Perhaps the Times’ neutral language was meant to counter the Taliban charge that they were proselytizers; to assert that they were humanitarians, not missionaries. And perhaps the genre of their deaths is yet to be worked through by their friends and families—and by all of us.

But imagine “Christian Martyrs” above the fold on the front page that first carried their story. How would readers have responded to the intrusion of deliberately religious language into the world of the well-educated Times reader, in which enlightened rationality is the lingua franca?

Giving the Witness of Blood

For some time, the religious and non-religious mainstream has consented to the criterion that public discourse must be accessible to all participants. While religious sentiments, of course, enjoy Constitutional protection, they should be left home when one goes public. Fundamentalists have rightly reacted to this trick played on people of faith. The price of admission to public debate is the agreement that one’s deepest motivations and the very foundations of one’s moral outlook—if religious—are unmentionable.

Perhaps this made sense when the discourse of the Enlightenment, which had set us free from priests and dogma and mystification, reigned as the single grand narrative of the modern world. But we are long since into the age of postmodernism, which celebrates multiple, competing narratives, all jostling with each other as varying communities of discourse meet and greet. Even the Supreme Court has decreed that religion cannot be the single discourse excluded from the cultural multiplicity that now expresses itself everywhere in public.

But let us return to the very idea of Christian martyrdom. Defined generally as undergoing death for the Christian faith, its golden age was the two centuries prior to Emperor Constantine’s conversion to Christianity. Which is to say, before Christianity began to make its long-running compromises with the state. Christian martyrs all had their feast days, the liturgical color was red to honor their shed blood, and churches were commonly built on the site of their executions. Indeed, until well into the 20th century of Roman Catholic Christianity it had been required that a consecrated altar must contain relics of a martyr.

A Christian martyr is a disciple and imitator of Christ who holds fast to the reasoned confession of faith and to a kind of life motivated by it, and ends up giving the witness (the meaning of the Greek word martyr) of blood. Surely there are some still today? Identifying them, however, is a politically fraught task, even for Christians. The last pope was not at all enthusiastic about joining the throngs who recognized Bishop Oscar Romero as a Latin American Christian martyr. It smelled too much of liberation theology to John Paul II. And it took the German people several decades after World War II before they could get used to calling Dietrich Bonhoeffer, the Lutheran theologian involved in regicide plots, a martyr.

The Hands and Feet of Jesus

For the secular world, however, the issue is its lagging understanding of what the Christian mission in the 21st-century world might be. Its ears are so accustomed to the arrogant certainties of the Christian Right, it can only assume that any Christian martyr worth his salt (surely an allusion to a pithy saying of Jesus) must be a Bible-smuggler who, in the name of Western hegemony, is determined to smother all exotic cultures, especially Islam, with civilizing Christianity. In fact, Roman Catholic, Lutheran, and most Protestant, including evangelical, mission is defined today by a servant model.

Modern Christians express their discipleship through medical, educational, agricultural service to those who need it, because they see the fully human Christ in all the faces of the needy and marginalized. The Christian martyrs in Afghanistan called themselves “the hands and feet of Jesus, not his mouth.”

There is a lesson here for “progressive religion” as well. Blasé secular liberals and fervent conservatives have long bought the notion that a religious Democrat is an oxymoron, and that any spiritually fervent Democrat is probably a hypocrite or a political panderer. No true Christian could be called to social democracy. Now progressive religion is called to take up space in the public square, to give its witness, to define itself, to identify openly and claim solidarity with the Christian martyrs in Afghanistan, protesting the easy assertion that anyone who takes Christianity seriously would have to be a fundamentalist. An absurdity, in this modern age.

Dangerous Discipleship

To speak of Christian martyrdom in this age is to grant that being Christian today should involve dangerous discipleship, also in a safe but utterly co-opting capitalist West. Add some salt to progressive religion by remembering the old Mennonite truth: Christians may regrettably be called to do the dying for a cause, but never the killing.

Surely the Afghan Christian martyrs can and should recognized in public discourse for what they were and are, and not just in the segregated space of a Christian funeral where no one will be disturbed by the assertion.

But wait! We now know what kind of funeral was held for these martyrs before they were buried in the Anglican Christian cemetery in Afghanistan. It was “mostly non-religious.”

I wondered what to make of this. The backstories of these aid workers were replete with deep Christian beliefs and commitments, but now their families have scripted a funeral seemingly discontinuous with that. Was this itself a certain kind of Christian witness, as when Jesus says don’t do your alms for show but secretly. Jesuit Karl Rahner used to speak of people in non-Western countries who somehow live Christ-like lives as “anonymous Christians.” Now we have explicitly Christian aid workers exercising their discipleship anonymously, rather than in the name of Christ. Should we regret this or admire it?

Perhaps this is evidence of “the world come of age,” as Bonhoeffer wrote from prison before his execution, in which Christian discipleship is a “secret discipline.”