The cloistered worlds of organized religion are often criticized for their lack of transparency. They have intricate customs, operate under belief systems that others question, and speak a language all their own. They tend to be exclusive rather than inclusive, building walls around their elite that shut out the common citizen. The same could also be said of academia, not to mention the world of art.

One man from San Francisco is taking on all three institutions; targeting priest, scientist, and artist in a playful rally against authority. Jonathon Keats calls himself an experimental philosopher—though novelist, journalist, performance artist, and mad scientist would all fit as well. In his latest work lies an invitation for not just cloistered specialists, but anyone and everyone, to participate. It used to be the exclusive domain of men of leisure to pursue God or science or art because they alone had the necessary combination of time and education, Keats argues, but now most people in the modern world have a modicum of both.

Yet Keats, 39 years old, feels there is a complete lack of curiosity on the part of the average person to ask the playful and profound questions at the heart of human existence. Scientists have specialized themselves into corners, the “sad consequence of the happy pursuit of knowledge.” The hoi polloi wait, Keats laments, for the artists to tell us the meaning of their art, the scientists to tell us how the world works, and the religious leaders to tell us right from wrong. We have become passive creatures.

To help combat this lethargy, Keats has turned to pornography. It began a couple of years ago with plants—showing zinnias uncensored footage of explicit pollination acts—but now it has escalated to porn for God.

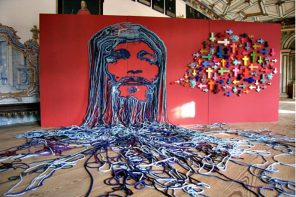

“Things are not going very well as far as the world is concerned, locally or universally,” said Keats. That’s the vague worry behind his most recent show “Pornography for God… and Pornography for Plants,” which closed last week at Louis V E.S.P., a not-for-profit gallery in Brooklyn, NY.

Because of the accelerating expansion of the universe, he figures we’re basically doomed, since every particle will—eventually—be so far from every other particle that there will be no form, no structure, no nothing.

“It seems like now might be a very good time for God to start making new universes that don’t have this design flaw.” He paused, then added, “Of course this is all speculative.”

A Temple to Science

In hopes of helping God along, Keats used a live feed from the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Switzerland, where scientists are smashing subatomic particles together in the hunt for the elusive Higgs boson and other things that might shed light on the origins of the universe. Votive candles and smoldering incense set on a deep red fabric made for an altar in front of the monitor, which showed cross-sections of the collider lit up with a spirograph of pastel whenever particles made contact. The result resembled a flower; perhaps the dieffenbachia watching plant porn on the other side of the room might have liked this, had they been able to choose. Keats’ hope is that by bringing together the most traditional of prayer spaces—the altar—with the most modern of experimental physics—the LHC—God will take notice.

There was at least some response from the fire gods, when one votive candle got a little frisky with the fabric draped over the altar. The gallery’s owner quickly stomped out the flames.

This kind of participatory effect is exactly what Keats is striving for. It might be a cadre of New Atheists who are screaming for the elevation of science to religion, but it’s Keats who, in 2008, actually created a temple to science. Dubbed the Atheon, it was an installation at the Judah L. Magnes Museum in Berkeley, with stained glass windows patterned to show cosmic microwave background radiation. Keats has also patented his brain, sold real estate in the extra dimensions suggested by string theory, and, as part of his God Project, conducted experiments with fruit flies and cyanobacteria in an effort to determine the divine taxonomy of God. Where, exactly, might Divineus deus fit on the phylogenetic tree of life?

“All of these projects are thought experiments, for lack of a better term,” Keats said. “They’re attempts to have people enter into an experiment that would otherwise be happening in isolation, on the page in a journal.”

For all the God-talk, Keats never once used a gendered pronoun for the divine, and ended long monologues on how to help relieve God’s eons of celibacy by saying, parenthetically, “If there is a God.” Keats definitively defines himself as an “absolute agnostic.” He finds the idea of believing or not believing with any certainty to be a quite boring approach to life. With glasses, a bow tie, and dirty blonde hair hanging nearly to his shoulders, he comes across as an overly earnest and sincere character. But sometimes the veneer cracks, a smile slips through, and out comes the kid who, when he was seven years old and living on Endeavor Drive in Corte Madera, California, sat on the sidewalk selling rocks. Not fancy rocks, just plain old bits of the planet. It was his first thought experiment, though he wouldn’t have called it that at the time.

Around that same age, Jonathon imagined what it would be like to become an Orthodox Jew, yearning for a way to rebel in a family of moderate Jews. He just barely fumbled through his Bar Mitzvah, but still goes to the synagogue with his mother, reluctantly.

“I really don’t like anything organized,” he said, “let alone religion.”

Still, he draws heavily from the Talmud, as well as such disparate influences as Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, The Little Prince, the book of Genesis, physicist Richard Feynman, and futurist Buckminster Fuller. In addition to his art, he also writes extensively. In a collection of fables, Book of the Unknown: Tales of the Thirty-Six (Random House, 2009), he spins off the Talmudic idea of the Lamedh-Vov—that, at any moment in time, there are thirty-six saint-like souls on Earth who are anonymous (even to themselves) and link humanity to God. His new book is Virtual Words, just out from Oxford University Press, evolved from his Jargon Watch column in Wired.

Though he’s received some blessing from the scientific world—a geneticist at UC Berkeley, a zoologist at the Smithsonian Institution, and other notables were on the board of Keats’ International Association for Divine Taxonomy—his work more often gets called absurd. He takes this as a compliment. “Absurdity is the circus quality of profundity. Where things get deep and disturbing, laughter is the only reflexive response. I see it as a way to accept, and indulge in, mystery as a part of life.”

But what he’s raging against most of all is not authority—scientific, artistic, or religious—but the lack of interest his fellow earthlings show in the world they inhabit. Too many of us value neither curiosity nor imagination. It’s what makes him choose the fairy tale as a writing device, and the Talmud as a muse. “Long ago, in a land far, far away” allows him to say what he feels he has to about what is happening here and now.

“What I want out of life is the wonder of childhood, the curiosity of childhood, everyday, for myself and for everyone else. The moment I start to self-consciously divide children from adults is the moment I lose sight of that broader focus.”

Which perhaps explains why his next project might leave God—if there is one—behind and, he says, turn to the wonder of toys.