“Show, don’t tell,” is common advice to screenwriters and fiction writers. In contrast to primarily non-fictioners like yours truly, those who compose films and novels and stories are rightly encouraged to avoid didacticism, to let the story speak for itself, never to make the meanings and morals too obvious.

Terrence Malick’s typically beautiful new film, To the Wonder, does exactly that, yet its depiction of the divine love/human love parallel is so elliptical as to flirt with inscrutability.

To be sure, Malick’s screenplay does telegraph the main theme of the work explicitly, usually in voiceovers (there are a lot of voiceovers) by a doubt-ridden priest played by Javier Bardem. Bardem’s priest wonders why we fall in and out of love with God, as we watch a couple played by Ben Affleck and Olga Kurylenko fall in and out of love with each other. If the parallelism were not clear enough, Bardem’s priest—played with brilliant understatement by an actor who often goes for the jugular—tells us how human love can serve as a gateway to divine love. Which (metaphysical spoiler alert) is roughly the final resolution of the film.

But it was no coincidence that the hipsters and film geeks lingered outside the Landmark Sunshine Theater, talking about what it all meant. This is a film that announces its theme, but then develops it not in a linear way, but through visual poetry, allusion, and metaphor. In this way, it is yet another of Malick’s brilliant evocations of the spiritual life. And perhaps a frustrating piece of art.

If you like, you can read To the Wonder as entirely allegorical, á la Life of Pi. Neil and Marina fall in love at Mont St. Michel in France, a revelatory moment akin to God’s covenant at Sinai. They live for a short time in paradise, but then exile themselves to a very contemporary Oklahoma: a land not of prairies and cowboys, but of pollution and strip malls. For a while, they stay in love, but the passion cools, and they begin to fight. They separate, Neil starts another relationship, they come back together, they fight again. And all the while, Javier Bardem wonders aloud why it is that God hides himself, why what is sometimes so passionate an embrace can grow so cold.

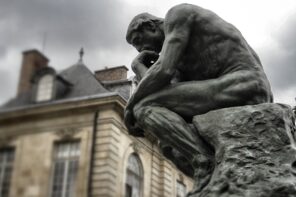

As with Malick’s other films, God is everywhere in To the Wonder, not only in the many scenes that take place in churches and cathedrals. Once again we run through fields of waving grass, stare at waterfalls, and gasp at sunsets. Marina dances ecstatically, in love both with Neil and with the majesty all around her. Malick has made a wise choice, however unintentionally, by making so few films (this is his sixth in almost forty years); revisiting these images provides a sense of continuity, even comfort. We are again in Malick’s mystical, Catholic world, as we have been in most of his other films; we are oriented again to his particular form of wonder.

As usual, Malick also provides us with some of the most sympathetic religious figures one sees on the American screen. Bardem’s doubting priest is perhaps a familiar figure, but we also watch him minister to prisoners, the ill, and the marginal. His God may be in eclipse, but his love remains strong. “What is this love that loves us?” he asks. Fortunately, the answer is shown, not told.

I think all of us who have been engaged with the spiritual life experience the oscillation that the priest describes, and that Nick and Marina display. Personally, there have been times in my life when I have been as God-soaked as Malick seems to be, and his films have placed me in a state of near rapture.

For the last few years, however, I have been more like the priest in To the Wonder. I have found my earlier passion cooling, my heart turning more toward the dharma and less toward the Western God, more toward contemplation and less toward devotion. Mysticism was once my passion—now I see it as a set of mind states which may be transformative, or may be dangerous. I have come to feel that the costs of religious fervor probably outweigh the benefits. Dancing Hasidim and joyous Christians no longer inspire me; they make me nervous.

Unlike the priest in Malick’s film, I no longer grope for the fiery faith I once had. On the contrary, I see it as more problem than solution. I am finding myself pulled toward the cool, the empirical, the contemplative, the Buddhist. I do not envy the vicissitudes either of the spiritual life, or of the wild Romantic life with which it is so frequently compared. As my beloved partner said to me as we exited To the Wonder, “let’s continue to see movies about people like this… but not be like them.”