Who better at this moment to challenge Pope Benedict’s recent un-excommunication of four right-wing prelates than another 81-year-old?

The recent papal edict re-enfolding Bishop Richard Williamson, a British holocaust denier and misogynist, has offended Jews, set interfaith relations back fifty years, repudiated Vatican II’s own views, and left the 40 or so women recently excommunicated because of their illicit ordinations breathless with indignation.

It has also has provoked a sharp response in a German newspaper, one that is being quickly sent around the world on the internet. Its writer is the eminent professor of ecumenical theology at Tubingen University, where he continues to teach eager classes, although he’s not permitted by Rome to teach as an official Catholic theologian.

It is just one of the paradoxes in the story of modern Catholic thought, and in the personal life of Rev. Hans Kung. He is, and has been since 1954, a Catholic priest. When he travels, he stays in the various rectories of Catholic parishes, hearing the confessions of the faithful, as he told us in Toronto in 2002, “as much as I am able.”

With his easy charm, impressive intellect, and clipped accent, Hans Kung, ever a sharp thorn in the Vatican, strides once more onto the ecclesial stage. The world-known Swiss Roman Catholic priest and theologian, who served as a peritus or expert at the Council (1962-65), he shared this responsibility with his German colleague, Josef Ratzinger, then a progressive thinker. How their paths would diverge.

To get right to the point, Kung in his article on February 3, wished Barack Obama were Pope. “The mood in the church is oppressive, reforms are paralyzed, and the church in crisis,” he says. “Benedict is unteachable in matters of birth control and abortion, arrogant and without transparency and restrictive of freedom and human rights.”

For Kung, Benedict should act as Obama has done, declaring a crisis, identifying the problems, proclaiming a vision of hope, revitalizing ecumenism, gathering competent colleagues of either gender, and using the power of his executive office to issue decrees (unhindered by such institutions as a democratically-elected Congress or a Supreme Court.)

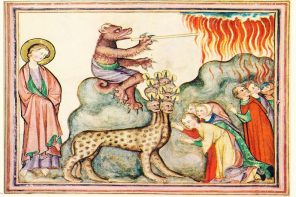

But no, “the Pope is reorienting himself backward, inspired by the ideal of the medieval church, looking toward the Council of 1870, not the one of 1965.”

Can the Roman Church, he asks, give birth to an episcopacy which does not conceal its manifest problems, theologians not afraid to speak out and a climate to encourage women leaders? Kung is playful: “Yes, we can,” he writes.

Progressives are delighted that Kung has spoken out. He manages to preserve a shred of Catholic credibility in the modern world. He enjoys the respect of other religions because of his tireless work developing a statement of a global ethic.

My long experience of his thought and personality began by stumbling on his 1971 book Infallibility?: An Inquiry. Short, sharp and readable, it was an account of the 1871 meeting of bishops which endorsed papal ambition by approving the notion of infallibility in matters of faith and morals. In this day, “creeping infallibilism” has enlarged its scope to include almost all papal pronouncements, to the profound detriment of ecumenical relations, freedom of thought and dissent, and even freedom itself to believe or belong. The book rather blew my mind.

That was in 1971.

Then life took me to Tanzania for the next three years, and there, a personal health crisis emerged. It was solved by African skill in a tropical hospital called Muhimbili, in Dar es Salaam. When I faced this trying moment, I wanted to be reading, not devotionals, but Hans Kung’s bracing On Being a Christian. To my amazement, into my three-bedded room, under mosquito netting, side by side with my two young Muslim co-patients, came my surgeon, who picked up the book and said to me “I am reading this man too.”

So we have the spectacle of two mighty and aged adversaries duking it out, offering deeply different models of ecclesiology. Not much more can be done to silence Kung. Humiliation can’t mean much to a man of 81 years. But his analysis offers a picture of costly resistance, tinged with wit and a kind of hopeless hope.

I’d call that faithfulness extraordinaire