The Vatican is up to its old tricks, investigating US women religious. Its “divide and conquer” technique pits the nuns who conform to male clerical expectations against those who assert their own moral and spiritual agency. But at the heart of the matter is the power to be “publicly” Catholic, something the men have long reserved for themselves. Now that Catholic women, including nuns, are saying “this is what Catholic looks like,” there is trouble in Vatican City and a new day for Catholicism.

Expected outcomes are predictable, and not pretty, as this latest round of intra-Catholic struggle unfolds. I think Roman Catholic Church officials have gone one step too far this time in their efforts to rein in the very women who make the Church look good in the wake of priest pedophilia crimes and episcopal cover-ups. They could save a lot of time and money by simply sitting down with some of these women and listening—yes, listening—to their experiences. I daresay they would come away edified by choices the women have made and inspired to live their own religious commitments with an ounce more integrity.

Three Nuns, or Three Million; It’s Not the Point

Two separate but interrelated Vatican investigations are in process this year. The first is an Apostolic Visitation to assess the “quality of religious life” of the roughly 59,000 women in canonical communities in the United States. Contemplative groups are not part of the exercise. The original intent was to figure out why the vast majority of the communities have far fewer members than they had in their heyday in the 1960s. (The median age for members is now over 70; only several hundred sisters are in their 30s.)

The concern for numbers is really, as subsequent materials from the investigators have shown, an entrée to looking at the lives, beliefs, and practices of women who strive to live coherently, melding their religious convictions with the needs of the world. Whether there are three nuns or three million is not the issue. What has changed (and the Vatican wishes hadn’t) is the fact that Catholic women, including nuns, think and act on their own without relying on male authorities to tell them how.

A second investigation is underway to look specifically at the Leadership Conference of Women Religious. LCWR is an association of the heads of the various communities that “assists its members to collaboratively carry out their service of leadership to further the mission of the Gospel in today’s world.” The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith initiated this study. That body is where the current Pope, then Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger, engineered much of the decades-long rightward movement of the Catholic Church. Now an American, William Cardinal Levada, is at the helm. He appointed Bishop Leonard P. Blair of Toledo, Ohio, to initiate a “doctrinal assessment” of the group. Of course I would suggest that the women consider a similar assessment of the curia—but that awaits a better day.

Areas of concern are the group’s views on homosexuality, the ordination of women, and the Vatican declaration Dominus Iesus, which asserts that Jesus is the unique and only road to salvation. The Cardinal’s assumption is that American nuns are accepting of same-sex love, supportive of feminist ministry (including ordination of women), and embracing of persons of many and no faiths. I only hope he is as right about their views as he is wrong about how to evaluate them.

An investigation of this sort is an unusual move against a group that is extremely diverse in its makeup. The mind boggles at just how one would assess such matters, given that American religious communities whose leadership populates LCWR are very diverse in their views. With war, economic inequality, ecological concerns, immigration, the well-being of women and dependent children, anti-racism work, and health care (to name just a few concerns occupying the vast majority of active nuns), this narrow agenda of Vatican concern is morally embarrassing.

It appears that the intention of the investigation is to maintain control over women and to preserve the Vatican’s Catholic view of the world via the hot-button issues that are contested in the Church at large. Though on Dominus Iesus, I wonder whether most members of LCWR have given it little more than passing notice. How these men flatter themselves to think that most of us read what they write, especially when it flies in the face of our experience and theological judgment. Maybe that’s the problem: they are losing ground and face by the day. Few people pay them much attention any more. Perhaps in intimate Vatican circles, officials do not even realize how limited their influence has become. Other Catholics speak, as in the case of the nuns, often making more sense with their lives than the documents do. In any case, the Vatican is under pressure from the Catholic religious right to enforce their version of orthodoxy and they appear intent to do so.

I am not a nun, never have been, and have no privileged information. But, as they say, “some of my best friends” are members of communities. I respect the choices they have made to cast their lots with one another. I also appreciate the dilemma many face as they seek to maintain fidelity to their God, their sisters, their church, their work, and themselves. As in any relationship personal or communal, life changes over time. The trick to a long-term one seems to be that all parties agree to keep growing together, a dynamic the Vatican shows few signs of embracing. That said, it is a mistake to analyze the nuns’ problems in a vacuum. They are part of the shifting power structure that has, for millennia, allowed a few clerical men to define and control the message and organization of Catholicism. Those days are over. Women and lay men consider ourselves just as Catholic as the Pope.

I have watched the kyriarchal Catholic Church long enough to know that process and product are deeply interwoven. In this case, the process of investigating women religious, many of them of retirement age and beyond, is one more effort to solidify the fractured clerical base; a last-ditch effort to reassert the monarchy’s will in the face of greatly diminished credibility. Chances of its success in the long run are slim even if there are some seeming “victories” for the right wing. What pains me this time is to see women pitted against one another, some doing the dirty work of the men who make decisions for them. I don’t understand why such women don’t understand that the same men who will promote them over their progressive sisters can just as easily promote others over them. It is the power dynamic, not just the people, that is at issue here.

Postmodern Catholicism is a different animal than its pre-Vatican II cousin. Catholics (women and men, lay and clerical, secular and religious) think for themselves, forming new syntheses of faith and solidarity. Nuns, perhaps more than many other Catholics, took the mandates of Vatican II seriously to rethink and reground their communities in the charisms of their founders, and to develop ways of living out those values in contemporary society. Their many ways of doing so have given rise to a variety of communities, ranging from very traditional to interreligious groups that serve as models for how the rest of us can live. This variety is emblematic of the whole Church, which has changed from being “Catholic” in the strictly identifiable Roman-focused way, to something closer to the original Greek sense of “catholic,” meaning universal, broad, and inclusive. It is this tension that is at play in the investigations.

The Vatican’s Congregation for Institutes of Consecrated Life and Societies of Apostolic Life (at the behest of Franc Cardinal Rode in December 2008) initiated the probe into the more than 350 US congregations of women. Mother Mary Clare Millea, leader of the Apostles of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, carries the awkward title of “Apostolic Visitator.” She was deputized by Rome to lead the four-step process that culminates in her confidential (the nuns will not see it) report to headquarters.

The initial step of meeting with leaders of the various communities has been followed by the recent publication of an Instrumentum Laboris that details the kinds of issues to be probed in the second phase; a questionnaire that leaders will be asked to answer for their groups. Then some groups (the ones whose answers may diverge from the Vatican’s norms, we may presume) will get a personal visit from a Vatican-approved investigator who has signed a loyalty oath to assure orthodoxy. The results of the whole study will be reported by Mother Millea to the Cardinal. After that, it is anyone’s guess. Oh, and the communities being investigated are asked to provide hospitality for the visitors they have not invited, and if possible, pay for their travel. Yes, something is radically wrong with this picture.

At first blush, one might be duped into thinking that the Vatican really wants the progressive religious communities to thrive and grow so that their work with migrants and other poor people, their ministries in hospitals and education, their work in parishes and base communities, their courageous efforts to support women who need reproductive health care, their work on farms and in retreat centers might flourish. Guess again.

The questions on the table include, for example, whether daily mass is a priority for the members and whether they “participate in the Eucharistic Liturgy according to approved liturgical norms.” Read: no feminist liturgies allowed.

The queries include how groups deal with “sisters who dissent publicly or privately from the authoritative teaching of the Church.” That classic “when did you stop beating your wife” question is really a warning to keep a short leash on those who might think for themselves. There are questions about the vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience: what they mean and how they are lived out. There are questions about finances and care of the elderly, but there is no inquiry into how the sisters love one another and how that love propels their ministry. There is no concern for how a community supports a nun who does civil disobedience and goes to jail to help stop war or nuclear weapons. A number of the questions are clearly designed to elicit answers the Vatican knows full well it won’t like.

The data will provide the pretext for concluding that the decline in numbers in progressive groups is a result of their lack of obedience and conformity to the men’s rules. Solution: tighten up the ranks. Enter the Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious, the alternative to LCWR; a group of conservative nuns who are dedicated “to foster the progress and welfare of religious life in the United States.”

This group now comprises the Vatican’s favored daughters, the good girls in veils whose model of religious life conforms to the dictates of Rome. For the record: the International Union of Superiors General, the highest-ranking such organization, threw its weight behind the American communities, calling their renewal work “a great gift, not only to the pluralistic society in which they live, but also to the universal Church.” Perhaps they envision more such investigations popping up around the globe.

LCWR has its roots in the Vatican-requested Conference of Major Superiors of Women (CMSW) in 1956 (beware the similar names). The women gradually developed their own democratic ways of operating; their three-stage presidency and their regional approach stood in sharp contrast to the increasingly more verticalist Vatican. Many of the women had served in Latin America, as per a 1960s Vatican request that each US community send 10% of their people South.

That experience, both direct and via other community members, served as one form of motivation (like anti-racism work, the women’s movements, and other social changes) for women religious to put less emphasis on conformity to rules and strict obedience and more on communal efforts to love well and do justice as adult moral agents responsible for their own well-being. By 1971, the CMSW voted itself a name change to the Leadership Conference of Women Religious with an ambitious agenda to provide education, networking, and other resources to facilitate and amplify the life and work of the communities.

There were women religious who feared that the shifts in name and focus would lead them away from what they considered the “essentials” of religious life. They formed the Consortium Perfectae Caritatis (CPC) to support their views. These include the centrality of the spousal bond (nuns as “Brides of Christ”), the three vows understood as narrowly as possible, and strict conformity to top-down community governance. Their views are now advanced by the Council of Major Superiors of Women Religious (which it seems the Vatican has in the wings to eclipse LCWR when the doctrinal probe is completed).

CMSWR recently published a book of essays, The Foundations of Religious Life: Revisiting the Vision. Complete with Nihil Obstat and Imprimatur, the five essays read like a blueprint for a 19th-century way of living. The premise is that a religious community, just as each member of it, is part of a “hierarchically-structured reality” in which obedience to higher authority is the norm.

Contra the theologians expressing more egalitarian views of religious life (notably Sandra Schneiders, IHM, Margaret Farley, RSM, and other highly respected scholars), the essay authors reject democratic governance and attention to inclusive process as inappropriate for religious communities. The devil is in the footnotes, where the conservative authors decry the progressive scholars’ “feminist overload and polarization,” and “artificial understanding of vows.” The point that they miss is that the more progressive nuns are not demanding everyone does it their way. The conservatives, on the other hand, take the Roman “my way or the highway” approach.

Coincidentally, or perhaps not-so, the book was launched at the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington DC, on the very day (May 16, 2009) that LCWR opened its impressive exhibit of the history of US women’s religious communities at a museum in Cincinnati. “Women and Spirit: Catholic Sisters in America” is a carefully researched, well funded, expertly mounted exhibit of the proud and stunning history of American nuns. The Vatican could save itself a lot of trouble by simply sending its staff to the Cincinnati History Museum where the exhibit is currently on display or to the Women’s Museum in Dallas, Texas, the Smithsonian in Washington DC, or the Mississippi River Museum in Dubuque, Iowa, where it will travel.

On exhibit, they would see the artifacts and read the stories of amazing women who are every bit as much the public face of American Catholicism as any bishop. They would learn about everything from the nurses who staffed a Navy medical ship in the Civil War to the sisters who raised seven million dollars and supported their colleagues working in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in the Gulf region. They would read about the women who established this country’s largest private school system and built some of its largest health care corporations. They would have the chance to be inspired by the nine sisters who have been killed in the last two decades in their efforts to bring about peace and justice abroad; most recently Sister of Notre Dame Dorothy Stang who took a stand in the Amazon that cost her her life. Without putting too fine a point on it, the research is all done and on the record to show the momentous achievements of American women religious. Any other investigation is superfluous.

That does not deter the Vatican from its tactic to divide and conquer women in what I predict is a futile effort to consolidate its waning power. The apostolic visitation will unfold as communities put in writing who they are and what they do. I anticipate that most will reject any sense of intimidation that might lead to self-censorship. The chips will fall where they may. Likewise, I expect that the investigation of LCWR will turn up just what their Summer 2009 meeting in New Orleans shows: namely, that they are about the work of love and justice with a preferential option for those who are in need. That will clearly not placate the Vatican on same-sex love, women’s priestly ministry, or whether Buddhism is a road to salvation. But it will demonstrate once again that Catholic women are not going away.

There is talk of dire consequences if the Vatican is displeased. Much of it is like the hype around health care; worst-case scenarios that are the creation of those who oppose change. My own guess is that the Vatican is not prepared to intervene much, if at all, in the everyday lives of the nuns. I believe those officials are banking that the fear instilled by its veiled threats (all puns intended) will be sufficient to bring the progressive nuns into conformity.

I submit that the progressive women have only to look at their own histories and realize that their ancestors in the orders paved the way for new, creative, communal ways of living their commitments as postmodern Catholics. Pioneer American nuns of three centuries ago made their way from Europe through dangerous seas; they headed West in covered wagons to found institutions that would serve the needs of poor and marginalized people. Surely their heirs, this generation of nuns, has the wherewithal to care for their elderly, act as responsible stewards of their resources, carry out their ministries, and explain firmly but collegially to the Roman men that they are an integral part of what American Catholicism looks like. That will be their legacy, enhanced by finding common cause with all of their sisters.

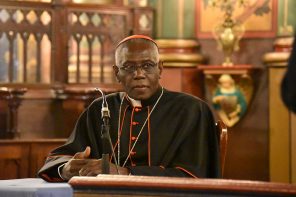

Note: Image is from “Women & Spirit: Catholic Sisters in America,” a traveling American history exhibit opening May 16 at the Cincinnati Museum Center, documenting the sisters’ contributions to shaping America’s health care, educational and social justice institutions. Sr. Hilary Ross (pictured) was an outstanding scientist and award-winning medical photographer who authored over 40 scientific papers on the biochemistry of leprosy. (Photo courtesy Daughters of Charity.)