“Evangelicals are more science-friendly than you think,” claims the headline of Cathy Lynn Grossman’s latest at RNS. The post examines a recent survey from sociologist Elaine Howard Ecklund, who found that 70 percent of American evangelical Christians do not view religion and science as being in conflict, and that almost 50 percent view science and religion as complementary. Furthermore, 84 percent of evangelicals say that modern science is “doing good in the world.”

While “more than you think” is too subjective a claim to really take issue with, what these statistics obscure is that evangelicals are nonetheless three times more anti-science than mainline Protestants, and those who do see religion and science as “complementary” would have science become much more evangelical-friendly.

The RNS story was picked up by the Huffington Post and the Washington Post, while Scientific American featured a different write up. It has all the ingredients for a good lede, since the news comes as both surprising and, for most of the readers of these publications, encouraging. But just how much harmony actually exists between scientists and evangelicals?

Ecklund, the director of Rice University’s Religion and Public Life Program, and her team had surveyed 10,241 U.S. adults about, among other things, their perceptions of conflict between religion and science. Ecklund’s paper, available here, contains two important footnotes to the “Evangelicals are Science-Friendly” hypothesis.

1) Science-Friendliness is Relative

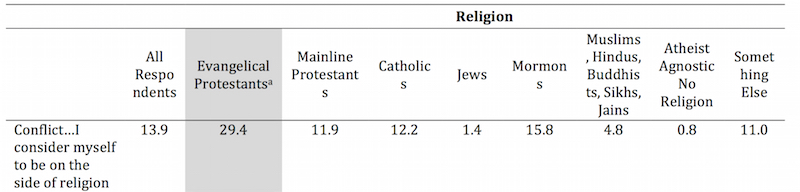

While only 29.4 percent of evangelicals reported that they considered science and religion to be in conflict, this is still almost twice the percentage of the runners-up, Mormons (15.8 percent). Here’s a comparison across all of the religious groups represented in Ecklund’s survey:

You’ll notice that pretty much no one is eager to tell the surveyors that science and religion can never get along. Even if only a minority of evangelicals assented to the “conflict thesis” about religion and science it’s important to note that this minority is relatively large compared to other mainline religious groups.

Evangelicals also reported being the least likely, of all groups, to take an interest in new scientific findings, and were the most likely to consult religious authorities if they had a question about science. Furthermore, Ecklund’s data reveals something about those evangelicals who chose the alternative positions of “independence” and “collaboration.”

2) Science-Friendliness for Evangelicals is Conditional

48.4 percent of evangelicals surveyed agreed with the “collaboration” view of science and religion, which maintains that “each can be used to help support the other.” This corresponds to the popular Christian notion that natural science offers insight into God’s design.

Accordingly many evangelicals reported that collaboration should be a two-way street. 59.6 percent of evangelicals, for example, strongly agreed that “scientists should be open to considering miracles in their theories.” By comparison, only about 36 percent each of mainline Protestants and Catholics strongly agreed with this statement, in keeping with the general average of everyone surveyed.

43.4 percent of evangelicals (twice the average) are young earth creationists, agreeing that “God created the universe, the Earth, and all of life within the past 10,000 years,” and 42.3 percent strongly favored teaching creationism instead of evolution in public schools.

This raises an important question: for American evangelicals, what does “collaboration” between religion and science look like? If it involves teaching creationism and young earth theories in the classroom, or retooling science to leave room for miracles, evangelicals will have a difficult time finding secular scientific collaborators.

The story here, then, isn’t so much that evangelicals are more science-friendly than you think (unless of course you didn’t think they were science-friendly at all). The story is that: they want a more evangelical-friendly science to collaborate with. This should come as no surprise. It’s increasingly difficult to maintain an antagonistic position toward science, broadly conceived, so many evangelicals likely view the conflict thesis as a losing position.

Under the auspices of collaboration, evangelicals can claim to be science-friendly without losing any rhetorical ground. They can maintain that in order to “meet in the middle” science must make room for miracles and creationism (which contains echoes of the failed creationist strategy to “teach the controversy” in debates over the teaching of evolution in public schools).

So while Ecklund’s survey does seem to document a significant shift in the language that evangelicals are using to describe religion and science, that change might ultimately be strategic and rhetorical more than, well, an evolution in evangelical respect for established science.

*Read a response to this post (and Andrew’s reply) here.