When people ask questions like “Why do we pick and choose our religious beliefs?” they usually don’t mean “we” but “they.” This is because within such a question, there is often an implied criticism of “religion”—however defined—that has not been swallowed hook, line, and sinker.

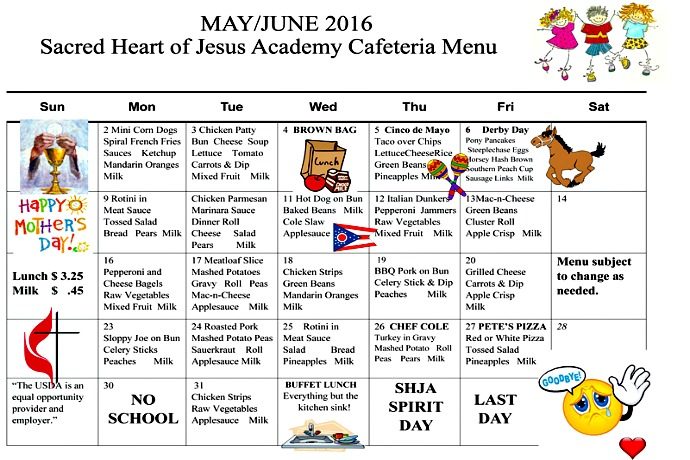

In this recent example, the question is being asked about America’s youth, and the answer is —what else?— “Blame social media.” A Baylor study, relying on information from Notre Dame’s National Study of Youth and Religion, finds that people who have been exposed to social media from young ages are more likely to agree that it is “OK for someone of your religion to also practice other religions.”

Without weighing in on the merits of this particular study (which requires login access), and after a couple of decades studying and teaching religion/s, I feel safe in saying that “we” pick and choose among tenets and practices because “we” are human and that is what humans do.

The term cafeteria Christianity is one I grew up with in evangelical circles, usually referring to those Christians who went to church on Sundays but then did whatever they wanted the rest of the week. In recent decades though, the left has gleefully co-opted the term, now applying it to supposed Bible-believers for selective neglect of certain teachings, like those on divorce or economic justice or contraception.

Both uses ignore the fact that human beings are reasoning animals. Some humans embrace the traditions they inherit, more or less as they receive them. This does not mean they are—necessarily—mindless idiots, but rather that these traditions work well for them for a variety of complex reasons. Other humans question, ignore, revise, rebel against, or even convert to different traditions. This does not mean that they are—necessarily—selfish, but rather that their forebears’ traditions do not work well for them, again for a variety of complex reasons. There is no simple way to explain why some of us submit to the whole shebang and others don’t.

In the spirit of gross oversimplification, I blame not social media but Constantinian Catholicism—not for intra-religious diversity, but for the idea that life should be any other way. Before 325 CE there existed a vast network of small clusters of pagan and Jewish Christians around the Mediterranean, mostly meeting in people’s homes, sharing a collection of related but not uniform sacraments and stories about Jesus.

But when Constantine became the Roman Caesar he decided he needed to build a more uniform religion for his empire. The religious power elite saw their chance and spent the next decades fighting over which version of Christianity would prevail, developing a biblical canon, determining official formulae for Jesus and the Trinity, and approving only certain ways of doing baptism and communion. By the end of the century, Theodosius I would outlaw all “wrong” forms of Christian belief and practice and punish them severely.

The emergence of an “official” or “orthodox” or “pure” Christianity in the fourth century, however, does not mean Christians haven’t continued to choose their religious beliefs and practices. In the eighth century, for example, the orthodox St. Boniface “had to” cut down an oak tree for Thor that remained sacred to Germanic Christians; the break-up between Eastern and Western churches in 1054 was largely a matter of Roman intolerance of Eastern variety; and medieval inquisitions existed for the purpose of cracking down on unlawful Christian variations. This is to say nothing of the picking and choosing unleashed in the 16th century by Luther and his ilk. (What could be more ironic than any Protestant pointing fingers at anyone about picking and choosing?)

Christian history, in other words, could be uniquely summed up as the millennia-long battle to define “true” Christianity. It didn’t have to be this way. In China, for example, most folks have no problem mixing and matching three or more religious traditions, and the idea of a unified Hinduism was more or less invented in the modern era. But most traditions have at least some who take a my-way-or-the-highway approach and have particular shibboleths upon which no compromise is possible. (What would mainstream religion coverage look like without them?)

Nevertheless, despite the best efforts of those who would make their traditions an all-or-nothing proposition, human beings have gone on picking and choosing, if perhaps never quite as unabashedly as young Americans in the 21st century.

I cannot say it any better than the ancient sage, Qoheleth, “What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done; there is nothing new under the sun” (Eccl. 1:9). For that matter, “Do not say, ‘Why were the former days better than these?’ For it is not from wisdom that you ask this” (Eccl. 7:9).

Religious purity—indeed any kind of pure cultural tradition—has always only ever been a dream for control freaks. It’s high time we gave that dream up, not only in the spirit of neighborly love, but also for the sake of asking more interesting questions.