S-Town, the latest multi-episode story from the creators of Serial and This American Life, begins with the promise of a true-crime investigation, descends quickly into quirky southern gothic, then stabs—in its final hour—at religion, complete with a unique “church,” its rituals, and its bloody sacraments .

[Spoilers ahead…!]The series centers around John B. McLemore, a clock-maker and clock-restorer, dog-fosterer and possible gold-hoarder, a polymath gifted with both “virtuosic negativity” and a knack for gab. A natural talker who sees corruption and decline all around him, equipped with arcane skills regarding clockwork and expansive facts on the cataclysm that is climate change, McLemore is like a producer’s dream of a late-night am radio host, and, as fate would have it, he contacted a This American Life senior producer—Brian Reed, who serves as narrator/protagonist of the podcast—with an invitation to investigate a murder in his hometown of Woodstock, Alabama, which he refers to as “shit-town” (the “s” in the show’s title).

McLemore’s voice is inimitable, seducing the listener into his jaded frame of mind. He describes his high school as “Auschwitz,” spins out racist conspiracies involving the local lumber yard, ridicules his town, his state, his neighbors and their elected representatives, claims expertise on the energy industry as well as what he describes as both sides of the issue of sexuality. Yet while the hours he spent talking to Reed provide plenty of hints of his fragile mental health and underlying depression, he can also be hilarious.

![]() Enter to win a $50 Amazon gift card!

Enter to win a $50 Amazon gift card!

Click HERE to take our 2-minute reader survey.

He’s capable of radio sprints, rants of such exuberance and creativity they demand to be heard. Amanda Hess, reviewing the series for the New York Times, calls McLemore, “the peppiest pessimist south of the Mason-Dixon line,” noting his “talent for profane rants about civilization’s downfall that he delivers in an Alabama drawl.”

There is more than a touch of exoticism in S-Town. The weird old south gets trotted out for display: a secret segregated room with an empty stripper pole, full of casually racist drunks; an anti-social eccentric commissioning iron gates for a dungeon beneath his house (or dog house?) where he plans to hide his hoard of gold. As our narrator says, at the end of episode six, less with condescension than an overly rosy romance for the land of Faulkner and O’Connor, “that’s something you could write a country song about.”

The series relies perhaps too heavily on the divide between rural folk and cosmopolitans—a divide imagined as much as real, or projected, by listeners onto the broke-down country types with their “fuck-it philosophy” versus the erudite loner, fond of spouting off the Latin names of regional plants as a display of dominance (and who, after all, reached out to public radio when he wanted a murderer locked up).

There’s a subplot about a country boy who makes good in the metropolis, moving to Manhattan and raising a bilingual son, and there’s one cringe-worthy moment when Reed tries to explain why he’s not judging an S-Town denizen as weird, but just a “complicated, normal person” who’s had some “very different life experience than I have.”

Sure enough. Perhaps, as both Spencer Kornhaber and Nicholas Quah have suggested, some of the perceived focus on rural versus urban is part of the collective psychic bruise that is our contemporary political scene, and perhaps, too, much of the show’s southern gothic sensibility is just part of McLemore’s rhetoric, his desire to demonize and speculate about the destruction of his homeland (“Mr. Putin, please,” he pleads at one point, calling down a bomb to wipe Alabama clean). McLemore obsesses over statistics proving, so he says, that his town has the highest rate of child sexual abuse in the state.

But this may be a layered concern, just as McLemore’s contempt for outward signs of a kind of class-based déclassé—like tattoos, or piercings—is significantly more complex than the flat dismissal it first seems.

Which is where religion comes in—what McLemore calls “church,” a violent, visceral, ritualized experience of community and, at the same time, self-absorption, communion and solipsism, body and mind, sacred and the determinedly profane.

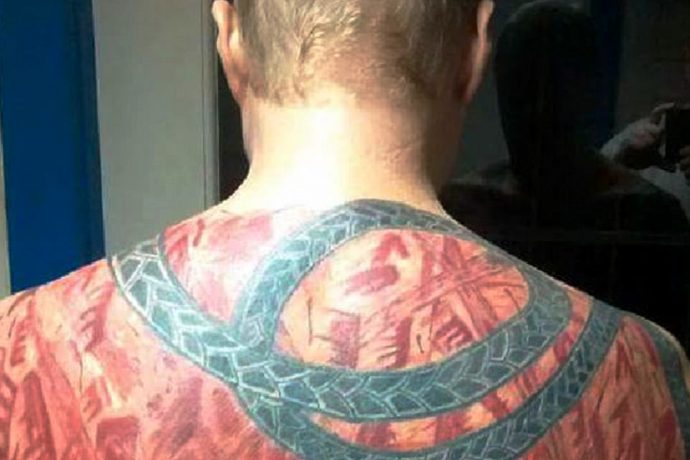

In the final episode we learn that the man who so despised tattoos, but had a significant number of them, acquired most of them in a short period of time, and acquired many through a particular practice in the back room of his own clock workshop. Paying one hundred dollars an hour to a tattoo artist, McLemore submitted to the needle, sometimes for a new piece, sometimes merely for more ink on top of old, a tattoo sunk on top of an existing tattoo, turning his body into a black palimpsest. Sometimes, even, the needles were empty, no ink at all, “no point to the tattoo,” as the artist says, except the pain itself, a simultaneous centering of the self and a distraction from consciousness—a kind of “therapy,” for an inveterate talker, that took him beyond words.

“We call that church,” McLemore tells Reed, walking through a series of correspondences, a parody of the sacred that is simultaneously a very literal experience of transcendence. “Wild Turkey is the holy water,” he says, of swilling whiskey from the bottle with the tattoo artist. The filthy, mercury-riddled room becomes, temporarily, “the sanctuary” just as the tattoo needles serve as “reliquaries.” The producers of S-Town gained access to video footage of this “church” in session, audio of which is played, a buzz and a moaning, a shifting register of agony-to-ecstasy in the voice of the man being pierced.

The tattoo artist speculates, for the show, that McLemore experienced “an endorphin high,” “a pain fix,” from these moments of “church.” Reed calls it “an elaborate form of cutting.” Aja Romano, writing for Vox, describes the podcast’s handling of his facet of McLemore’s life as exploitative, reading the link posited by Reed between this bodily practice and queer sexual desire as pathologization.

“John has been asking the straight object of his sublimated attraction to help him engage in a ritualistic pain fetish,” Romano writes, yet we’re told that the situation is just another form of self-harm.

While McLemore’s sexuality is a concern of the show, it remains enigmatic, the complexities of his desires for others—those who would be lovers, those who were friends, even the dogs he raised—treated with empathy. We know he made plans for his pets to be euthanized after his own death, for instance, and that once introduced to Annie Proulx’s short story “Brokeback Mountain” he read it with something like ritual frequency, calling it “the grief manual.” Reed, admirably, doesn’t theorize further regarding sexuality, or the relation of “church”—which also involves repeated nipple piecing—to titillation or desire.

But there is more to McLemore’s own description of “church” than two men and a tattoo gun. There is intoxication, the shared revelry of drunkenness, a kind of male socialization that mirrors, in private, more public forms in Woodstock. There is also a literary angle, reading and discussion of various texts and ideas, from Guy de Maupassant to life after death. Most notably, the men discuss the work of French philosopher George Bataille, the man who sought mystical experience in sex and pain, who theorized the limits of consciousness in extreme states of the body, who dwelt on inner experience while romantizing the rupture of self that came with intoxication or orgasm or agony. Bataille, perhaps most importantly, imagined all of these concerns in relation with an ideal of community, seeing the limits of the subjective self as both problem and tool.

McLemore, who exerted his creativity at clocks and hedge labyrinths and a 53-page illustrated manifesto documenting society’s continuing decline, seems to have likewise engaged constructively in a kind of experiment in Bataillian theory, entering into an altered state in a back room in small town Alabama in order to instantiate what Bataille called “impossible community” and “limit-experience.”

The “church” of S-Town, beyond the blood and whiskey, represents a serious attempt at finding—at viscerally experiencing—a sense of meaning in life.

That the audience doesn’t hear about this “church” until the final episode feels both like a cheat and a simplistic gesture toward closure for the show. Reed pulls the same final hour reveal with the theory that maybe McLemore had mercury poisoning, meaning maybe he was just crazy. That religion gets shunted off to the same spot, given the same lazy deus ex machina treatment, reveals more about the discomfort the show’s producers have with this material than it does about “church” as an explanatory key for McLemore’s life—or his death by suicide.

This “church,” admittedly, is difficult to conceptualize. The very nature—the very point—of such an experience resides in its being experience, going beyond thinking, theory, and language. With the widespread popularity of S-Town, the torrent of critical responses will not end soon. Hopefully some of these will wander through, and offer some mapping of, the labyrinth of McLemore’s “church.”

This kind of analysis will require moving beyond the framework of traditional theology, which hemmed in the interpretations offered by Kaitlyn Schiess in a recent Christianity Today piece on the show (one that linked McLemore’s horology, rather optimistically, to that of the Christian Creator God). “McLemore’s own complicated relationship with Woodstock and its cast of characters is an honest and stirring picture of what human identity looks like in a fallen world,” Schiess writes. “McLemore is painfully aware that the world he inhabits is tragically broken, but he still finds ways and places to create beauty and relationship.”

Listening again to McLemore’s groans and whimpers as he submits to the needle, as he prays, drunk on sacrament, at his peculiar shit-town “church,” the modulations of his voice demand reconsideration of terms like brokenness, beauty, and relationship.

The community around the bottle and the needle in the back of the clock workshop offers a very different model of, to riff on McLemore’s own desire to reclaim and tweak the words of tradition, “congregation,” or “sacrifice,” or the “numinous.” Which is not to say that this “church” isn’t an experience of beauty, of relationship, and of a transcendence of brokenness in pursuit of some idealized whole, merely that, at its best, S-Town prompts us to radically re-imagine our categories, our theories of being, and our preconceptions.