The numbers are hard to pin down, but roughly 1.1 million Americans keep kosher in their homes. Around 15 million are vegetarian. Meanwhile, according to a 2013 survey, more than 100 million Americans are trying to cut down on gluten, and (as of 2014) more than 10 million households are gluten-free. Simply put, gluten avoidance is the reigning dietary restriction of our time.

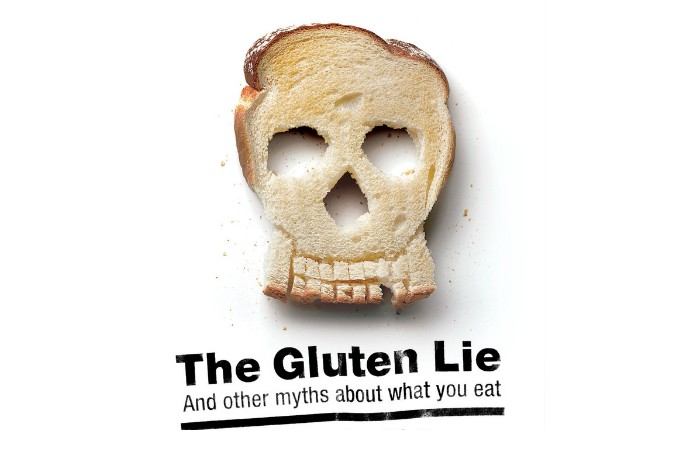

The Gluten Lie: And Other Myths About What You Eat

Alan Levinovitz

Regan Arts, 2015

Yet somewhere in our collective search for health, security, and purity, gluten transformed into a mainstream taboo. Scientific-sounding language (and savvy marketers) have driven this transformation, though one suspects that mass gluten avoidance has more in common with religious food restrictions than it does with anything premised on actual medical data.

Fittingly, Alan Levinovitz is a religion professor at James Madison University and a chronicler of our peculiar dietary culture. In his new book, The Gluten Lie, Levinovitz digs into the fear and moralizing that surrounds dietary fads, including gluten avoidance and the MSG scare.

Reached by Skype, Levinovitz spoke with The Cubit about paleo dieters, grain-free monks, and why Fitbit represents a cultural descent into profound moral vacuity.

You’re a scholar of classical Chinese religions. How’d you end up writing about gluten?

Over two thousand years ago, there were these proto-Taoist monks in China who advocated strongly for a grain-free diet. [They claimed that] you could live forever. You could avoid disease. You could fly and teleport. Your skin would clear up.

I saw this countercultural rejection of grains, and then I saw almost the exact same thing, with the same kinds of hyperbolic claims, happening again with books like Grain Brain and Wheat Belly. And I thought to myself, you know, it’s funny, people are trying to debunk these fad diets with scientific evidence, but what they’re not realizing is that really these beliefs aren’t scientific at all. They’re wrapped in scientific rhetoric, but ultimately they’re quasi-religious beliefs that are based on superstition and myth.

Food rituals, food taboos, dietary demons, dietary myths, magic diets, guilt, sin: why do we apply so much religious language to food?

Virtually ever religious tradition has had food taboos and sacred diets. I think part of the reason is that food is something that we have direct control over. It crosses the boundary in a very personal way: we take something outside of our body and put it into our body. Eating is very personal, and it’s easy to invest those kinds of things with religious and ritual significance.

With diets today, there seems to be a lot of fear involved, too.

It’s terrifying to live in a place where the causes of diseases like Alzheimer’s, autism, or ADHD, or the causes of weight gain, are mysterious. So what we do is come up with certain causes for the things that we fear.

If we’re trying to avoid things that we fear, why would we invent a world full of toxins that don’t really exist? Again, it’s about control. After all, if there are things that we’re scared of, then at least we know what to avoid. If there is a sacred diet, and if there are foods that are really taboo, yeah, it’s scary, but it’s also empowering, because we can readily identify culinary good and evil, and then we have a path that we can follow that’s salvific.

I keep thinking of Mary Douglas’ classic Purity and Danger—this idea that cultures declare things unclean not because they’re actually dirty, but because people need to impose order on the world.

What Douglas would say, I think, when she looks at a lot of these diets, is that they’re really about being able to divide up the world into categories—which things are morally pure, and which things are morally impure. It’s so hard for us to understand how something that has an evil origin, such as factory-farmed meat, might not also actually be evil for us physically.

Douglas points out that it’s not all about science or health, but we like to think that it is. I think the same is absolutely true for fear of foods like sugar, for example, where what we might fear is the pleasure, but then we want to rationalize it by saying that what we really fear is its effect on our health.

Should we respect that fear, even if the evidence doesn’t always back it up? I feel like its acceptable right now to critique New Age eating habits, but I would never do the same about, say, kashrut or halal diets.

I have no problem with religious diets. What I have a problem with is religious diets masquerading as scientifically sound dietary advice. It’s one thing to say, “Hey, I just think it is immoral to genetically alter plants, and therefore I don’t eat them because they represent modern evil.” That’s fine, as long as you stop there.

But when you try to bring in scientific evidence to show that actually your dietary choices are better for your health, that’s where I think we get into a huge problem. It’s the conflation of ideological diets with diets that are supposed to help cure cancer, for example, that’s really dangerous.

As you point out, even the most mystical sounding diets or foods will often include a (pseudo)scientific justification. Why do consumers and marketers gravitate toward scientific language?

People want to make empirical claims about the effects of diet. I think that scientific rhetoric has a certain kind of plausibility and objectivity built into it that many people no longer associate with religion, and certainly no longer associate with religion in regards to nutrition.

Even if its scientific justifications are questionable, doesn’t something like the Paleo diet help people eat more healthily? I mean, raw vegetables are probably better for you than TV dinners.

Well, I want to be very careful, right. Raw vegetables are not better for you than TV dinners, without any further context. If one person only eats raw broccoli, while you eat a lot of Amy’s frozen enchiladas, you’re probably better off than the person who only eats raw broccoli. I understand that’s not what you’re saying, but there’s a lot of that oversimplification in diet rhetoric.

No, that’s a good point. I guess I’m saying that we just need to have stories, sometimes.

I can tell you a familiar story: long ago, humans lived in an organic, all-natural, divinely-designed garden, free from pesticides and GMOs and processed grains and sugar. Then one day an evil advertiser came along and hissed at them, “Eat this fruit.” And then, boom, we’re cursed with mortality, marital strife, pains giving birth, and we have to do agriculture.

For paleo, the stars are no longer Adam and Eve. It’s Paleolithic man. But Paleolithic dieting has a ring of scientific authenticity to it. They evoke evolution instead of God. It sounds very scientific, but just seeing the way in which it parallels this commonplace myth of paradise past should make us initially suspicious. When you start to look at the evidence for it, it falls apart. You realize there’s lots of cherry-picked data.

But it’s a lot harder to get a good story out of something like, “Eat a lot of different things in moderation,” even if that’s probably better advice.

Science is not great at constructing narratives. That’s its virtue and its downfall. Scientific inquiry has to divorce itself from what makes the best story, and science writers, myself included, are in the business of making science compelling by telling stories.

It’s true: we report scientific findings in a narrative form.

One important point: science is filled with conditionals and religious literature is not. Any religious literature, any revealed scripture, doesn’t have lots of mights and coulds and maybes and further revelations are needed. There’s nothing wrong with that kind of certainty in religious texts, though some people might argue that there is. But when you bring that kind of certainty to science, you end up lying about the certainty of the science, you end up exaggerating the scope of the claims. In science, exaggeration is just deception.

But exaggeration sells really well, doesn’t it? Gluten is great business.

Absolutely. And the thing that’s so troubling about gluten is that, like most things, it’s complicated. There are many people with celiac disease for whom gluten is extremely dangerous, and the scientific story on non-celiac gluten sensitivity is far from settled.

Yet people don’t want to admit that uncertainty. They either want to crucify gluten as the cause of all modern health scourges or they want to say, well, gluten-free dieting is complete B.S. The truth is somewhere in between those two poles.

When it comes to food rhetoric today, the industrial world is often held up as the source of evil. Are there other evils you see coming up in the rhetoric that surrounds these diets?

I think there’s a worship of nature, which ties to modern industrialism, but is slightly different. People have created a dichotomy between natural and artificial. In a time of hipsterism and crises of authenticity, no one wants to be artificial. There’s a way in which I think an emphasis on natural foods grows out of an anxiety about disappearing standards of authenticity in modern culture.

That blend of nostalgia and anxiety reminds me of the main character in Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris who romanticizes 1920s Paris, until he actually travels there and discovers that Parisians of the ‘20s are fantasizing about the 1890s …and so on. We look to other times and other cultures for supposedly healthier, more authentic ways of eating.

There’s this idea, and it makes a lot of intuitive sense, that if we’re suffering, and we don’t have solutions to our own problems, we must look outside of our culture for those answers. If we’re powerless to solve them, maybe other cultures have the solution. So we look to Tibetans for bulletproof coffee, for example, or we look to the past where things are distant enough where we are able to romanticize them.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, there’s a huge push within China to reject Traditional Chinese Medicine. This romanticization of what is outside of one’s culture, especially in order to deal with health problems, is something that is really common, and something we ought to avoid.

At the same time, our culture’s eating habits seem to hurt people. Is looking outside of our own culture sometimes a good thing?

Sure. But I think it’s dangerous to say “our culture’s eating habits.” Our culture’s eating habits are extraordinarily varied. Yeah, it’s great to look at another culture, break it down in all of its complexity, and see if there any specific things that these people do that can be of benefit not just to them, but to us.

What works for another culture might not work for our own culture. People ask me, what’s the harm? Why not just go gluten free? And the answer is that going gluten free has all sorts of effects. It affects your relationship with your friends and family. It affects your relationship with your own past and foods that you love. While there might be some culture in which celebratory foods don’t typically contain gluten, that’s not our culture.

Do you think there’s an incentive to setting yourself apart from the culture at-large? Uniqueness can carry its own social value.

I think a lot of people are distinguishing themselves by adopting ascetic diets. Religious people have done this since time immemorial. To show that they have some kind of strength to distance themselves from the material world, they adopt ascetic diets.

But then to assert that your ascetic diet in turn makes you physically superior to others, in addition to being morally superior, is a step that I wouldn’t want to take. Especially nowadays, people don’t want to assert moral superiority over other people, so instead they assert physical superiority. But I think also that’s a proxy for asserting their moral superiority. Saying that I’m living a healthier life is the only courteous way left of saying I’m living a better life.

We’re so afraid, and rightfully so, of judging ourselves better than other people, that now we have proxy words like “healthier” or “longer-lived” to stand in for the desirable moral judgment that we are superior to others.

How much do you think fad dieting is a response to the massive expansion of food choices available to us? It can be a confusing world to navigate—so many options, so many ethically-fraught factors.

I think [fad dieting] is a reaction to the proliferation of science. The voices of science used to be largely monolithic. You couldn’t go online and get 16 different authoritative declarations about what your diet can be. And now you have that.

People are picking and choosing from all of these dietary authorities to put together their own dietary faith. They don’t necessarily think it’s right for other people, but they also don’t want other people to challenge them, either. And then, there’s the fact that because of this proliferation of diet authorities, people want to seek refuge from that chaos in a single authority.

It also legitimizes fringe authorities, because they can use that diversity of scientific findings to make themselves seem no less authoritative than anybody else.

A deluge of information can actually complicate things, can’t it? Will health-tracking apps like Fitbit make us even nuttier?

What we’re doing with these trackers and these obsessive diets is giving ourselves an increasingly quantifiable way of saying that we are better than the other people. These things don’t work. They’re a marketing gimmick. They aren’t going to help you lose weight. It’s another ritual—a modern technological ritual that people are adopting in order to feel as though they’re living better.

This takes us back to religion. There are a great many things about religion that are extraordinary. It helps us ask and answer questions about mortality, about beauty, about goodness, about truth, that really can’t be addressed by scientific studies. I think that it is a pity when people start trying to answer those questions with the kinds of foods that they eat. It’s kind of sad, right, that now the way we confront death is by avoiding Fritos. What a pathetic ritual, right? Strap on your Fitbit and shop at Whole Foods instead of, you know, sitting down and thinking about Job.

And the sad thing is, it’s really easy to judge people on the basis of what they look like. We have this problem with race. In the same way, it’s really easy to look at someone who’s obese and say, “Oh look at that person, they’re not living as good a life as I am. They’re not as good on the inside because I can tell their outside isn’t good either.” Honestly, it’s disgusting to me that we’ve taken the great rituals of religious traditions and swapped them out for Fitbits and weird prohibition diets, and we think that that’s the best way to figure out how to be good and how to get back to a time when humans were better.

It’s funny, in my notes on your book, I have written next to the section on Fitbits, “perverted form of mindfulness?”

It’s interesting you bring that up. Some of the academic work I’m interested in right now is on mindfulness, and the way in which mindfulness traditions themselves get perverted when we turn them into ways to lower our blood pressure or reverse aging or burn fat. [For a contrasting view, see this recent RD piece].

What’s yoga good for? What’s mindfulness good for? Well, it’s good for—and then substitute whatever health condition you want to deal with. I just think it’s kind of sad that that’s where we would invest so much of our ethical energy. It’s an incredible amount of time and effort. And for what? And for nothing. To look better.