As a reporter who has covered the religious right for years, I frequently get asked two questions:

1. Is the religious right dead?

2. Who is the new leader of the religious right?

Let’s just say, to question number one, no, OK? And now, post-Beckfest, the new Question is: is Glenn Beck the new leader of the religious right?

As evidenced by the Black Robed Regiment, Beck is cultivating the support of religious right leaders who like his new God gig. After all, there have been worries along the way that the tea party — and possibly Beck as a de facto leader or at least inspirer of them — didn’t have enough reverence to God, and with the tea parties center stage, the religious right might take a back seat. Beck went to school with David Barton, and he emerged with plenty of reverential Godtalk — but more notably, at the Lincoln Memorial, he had a lot of reverence to Beck and his vision for America, which he put on par with Martin Luther King, Jr., Abraham Lincoln, and George Whitfield.

Evangelicals prefer reverence to Jesus — something on display at his Divine Destiny event on Friday, but not at his much bigger rally on the Mall Saturday.

What struck me most about Beck’s own speech on Saturday was how not-evangelical it was. That’s not surprising, of course, because Beck’s not evangelical. And even though, as I wrote yesterday, Beck’s “America must turn to God” isn’t original, it was distinct enough from the numerous evangelical rallies I’ve covered that I think Joanna is right in dubbing him the first Mormon televangelist.

At an evangelical rally — or shall I say revival — I would have expected him to discuss personal salvation and redemption, an emphasis on the notion of the redemptive power of Christ to wipe away not just individual sins, but the country’s sins. (That, of course, would have required Beck to tread into overtly political territory, something he pledged not to do but was obviously his purpose.) That Jesus is the sole path to redemption. That a country without Jesus has lost its way to the secularists. That God is relying on you — everyone is an Esther — to save their people and their country from ruin.

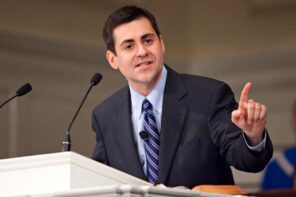

Evangelicals — beyond Richard Land talking to NPR and the Washington Post — are starting to express their unease not just with Beck’s Mormonism (although they are indeed uneasy with that) but with what I’ll liberally paraphrase as Beck’s flim-flammery. Russell Moore, Dean of the School of Theology at the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, writes in a post that is starting to make its way around the internet:

It’s taken us a long time to get here, in this plummet from Francis Schaeffer to Glenn Beck. In order to be this gullible, American Christians have had to endure years of vacuous talk about undefined “revival” and “turning America back to God” that was less about anything uniquely Christian than about, at best, a generically theistic civil religion and, at worst, some partisan political movement.

Moore goes on to criticize not just the left but the right as well, for politicizing religion and not putting Jesus front and center:

Rather than cultivating a Christian vision of justice and the common good (which would have, by necessity, been nuanced enough to put us sometimes at odds with our political allies), we’ve relied on populist God-and-country sloganeering and outrage-generating talking heads. We’ve tolerated heresy and buffoonery in our leadership as long as with it there is sufficient political “conservatism” and a sufficient commercial venue to sell our books and products.

That’s a harsh indictment not just of Beck, but of the religious right environment that produced the Beck of “populist God-and-country sloganeering and outrage-generating talking heads.” In other words, Beck didn’t invent that — Moore’s suggesting he’s riding the religious right’s coattails, coattails of a movement that itself has lost its way.

Still, though, the politicized religious right has no choice but to play with Beck. He brings them an audience that’s likely to buy their ideology and vote for their favored candidates. But whether they look to him as a leader — and whether their minions see him as such — is a different story entirely.