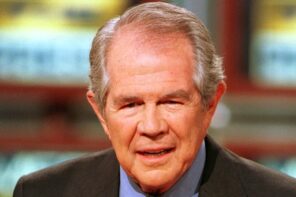

The backlash from evangelicals against Pat Robertson’s advice that a man should divorce his wife afflicted with Alzheimer’s disease was swift and intense. The Christian Post quotes “brain expert” Dr. Daniel Amen suggesting that the one-time icon might be mentally ill:

Amen, who will be taping shows for PBS that include discussions on preventing Alzheimer’s, told The Christian Post that although he had not seen the controversial segment, Robertson’s remarks were puzzling.

“I think it’s wrong and I think it sends the wrong message. I think it shows such bad judgment on Pat’s part that I would wonder about his brain,” Amen said. “The hallmark of a good brain is to have forethought, judgment, and empathy. I haven’t read his whole statement so I want to be cautious in my remarks, but his comments are hurtful.”

You really need a brain expert for that?

Turns out, though, that Amen’s expertise doesn’t really hold up in the face of scientific evidence (not that we needed medical expertise to question the proper functioning of Pat Robertson’s brain) but he is himself a televangelist of sorts who claims that he’s discovered a way to prevent Alzheimer’s. (In addition to his work with PBS, Amen also is advising Rick Warren’s Saddleback Church with a health campaign called the “Daniel Plan,” according to the Christian Post.)

Amen has been the subject of intense criticism from the medical community over Alzheimer’s prevention. A 2008 piece in Salon by Robert Burton, the former chief of neurology at Mount Zion-UCSF Hospital, debunked many of Amen’s claims:

One of the messages of Amen’s PBS special and his book on Alzheimer’s is that early detection of A.D. can lead to methods that both slow the progression of the disease and prevent it. But this opinion isn’t shared by the vast majority of the medical community. Despite decades of studies, there are at present no definitive long-term treatments for A.D. or its prevention, as Amen would have viewers and readers believe.

At the core of Amen’s crusade — both in print and on TV — is a type of functional brain imaging known as SPECT (single photon emission computed tomography), a radioisotope-enhanced CAT scan that measures blood flow in certain regions of the brain. Amen relies heavily on SPECT to make an early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s so that it can be prevented. But medical science does not support his view. . . .

Faced with the prospect of overlooking a preventable disaster, the public is a sitting duck for Amen’s medical sales pitch. And what exactly is he offering that the rest of the medical community has overlooked? He reiterates the usual common-sense recommendations: mental and physical exercise, good nutrition, avoidance of excess alcohol, not smoking and stress reduction. All of these are modestly helpful in preventing general cognitive decline. But none of them has a specific anti-Alzheimer’s effect.

The rest of his recommendations, including those gathered from his Web site and other published writings, aren’t specific evidence-based treatments for A.D., but rather a potpourri of unproven treatments, such as antioxidants and proprietary nutraceuticals.

Amen has said he was called by God to do brain scans, an argument similar to that made by Robertson as to why people should listen to his ramblings. Amen claims to be able to ascertain a presidential candidate’s brain function with a brain scan (you can get one in his clinic for $3,250, according to a 2007 article in Slate), to determine whether they would be more like Hitler or Gandhi. The medical experts are, again, unconvinced:

Amen admits that “all doctors might not agree” with the interpretations he draws from these brain scans, which is a bit like saying that all paleontologists might not agree with Kirk Cameron‘s interpretation of the fossil record. In fact, Amen’s work is well outside the mainstream of psychiatry: There’s little evidence to show that brain scans can be used to separate a “normal” brain from one that suffers from autism, Alzheimer’s, or mood disorders. (Some physiological differences have emerged from group studies, but they’re too small to see on a subject-by-subject basis.) The American Psychiatric Association views this work as exploratory and inconclusive (PDF), and major insurers won’t reimburse for the expense.

But Amen’s employees are ready to prescribe an entire treatment program on the basis of these scans. Once they’ve identified your particular brain problems, you’ll be assigned a smorgasbord of flaky and unproven therapies. In addition to the talking cure and psychoactive drugs, your treatment might include hypnosis, prayer, meditation, biofeedback, dietary supplements, hyperbaric oxygen treatment, transcranial magnetic stimulation, and eye-movement desensitization.

Perhaps Robertson’s problems, which don’t really require a medical diagnosis, are one thing Amen is qualified to comment on.