Lawyer-approved CIA torture, “renditions” to other state torturers, mechanized assassination-by-drone (with many thousands of innocents collaterally killed), bloody and chaotic regime change premised on falsified intelligence, the moral injury suffered by soldiers in America’s interminable twilight wars, what the liberators saw in the Nazi death camps, the ongoing legacy of American lynching: these are all things still living in our consciousness that are too horrible to think about and almost unbearable to write about.

Draw Your Weapons

Sarah Sentilles

Penguin Random House

July 2017

Then, in an odd parallel, the tradition of apophatic theology that insists there are things too wonderful/terrible to speak about and write about: things touching on God’s glory, God’s justice, and God’s mercy. A tradition that asks us to shut up for God’s sake.

Only a thinker as inventive as Sarah Sentilles could put these two variations on what is literally unspeakable into the same book and thus spur her readers to start thinking in fresh ways.

Some reviewers have cited Susan Sontag as a primary influence for this book, and Sentilles does indeed respond to Sontag’s work, to Regarding the Pain of Others in particular. But her style is very different from Sontag’s mode of sustained argument. What Sentilles gives us here is a fresh and original style, a bricolage of her own focused meditations interspersed with insights and aperçus from Roland Barthes, Virginia Woolf, Walter Benjamin, John Berger, James Cone, Jeanette Winterson, Pierre Bourdieu, Antoine de Saint-Exupèry, Judith Butler, Gordon Kaufman, Emmanuel Levinas, and Ariella Azoulay, among others.

The result is bracing and disturbing at the same time. For those with eyes to see, there’s plenty of theology here, but none of it is force fed or developed beyond the level of suggestion. In that tantalizing way of negative theology, it is what Sentilles does not say that lingers in the mind: in regard, for example, to the raging destructiveness of a God who wiped out almost all of creation in the Great Flood, an event that ends with Noah himself burning the very best animals he had saved in the Ark. Or the unfathomable ideation of a God who would send Jesus into direct and dangerous confrontation with Satan right after pronouncing himself “well pleased” with this “beloved son.” Or the historical origins of waterboarding as forced baptism: as an “act of salvation,” according to its Christian practitioners. Or the unimaginable sufferings of the tortured Abu Ghraib prisoners in relation to the Stations of the Cross. Or the reconstitution of the mystical Body of Christ in the Eucharist—and a grief-stricken Christ’s own extraordinary reconstitution of the long-dead body of Lazarus. Or the linkage between the veneration of saints’ relics and the popularity of lynching souvenirs during the heyday of Christian America’s anti-black savagery.

Sentilles raises but does not answer the question of whether photographs of suffering, photographs of those whose lives were brutally snuffed out, expand or diminish our human sympathies.

Like Sontag, she is not interested in “sympathy” as a way of distancing and even excusing ourselves from the horrors we witness via a photographic record. She is interested in sympathy as solidarity, as redemptive action in “transformational pacifism” of the Ghandian variety. But there remains Judith Butler’s question of whether we are even capable of seeing what we are seeing in certain photographs. There remains the question of whether we are capable, per Emmanuel Levinas, of discerning God precisely in the human “other.” There remains the question raised by John Berger as to whether, in holding up to our view a photo documenting human evil, we have “failed before [we] have even begun.”

Toward the end of the book Sentilles drops into her text a handful of biblical quotations—from the Creation story, from the Akedah of Gen. 22, from Psalm 139, from the Book of Job, from the Sermon on the Mount, and (most interesting, in my view) from the scary “Little Apocalypse” sayings attributed to Jesus (Mt. 24, Mark 13, Luke 21). Again, her method is not to explain or expatiate upon these quotes. It’s left up to us to connect the dots. This method may well annoy some readers, but I think it works exactly as intended. As she writes, “The question to ask is what the world of the text does to someone who submits to its vision.”

Lest anyone think that this new book is merely a farrago of random bits, it does have a unifying narrative structure centered on the author’s interactions with a saintly American couple: Howard and Ruane Scott.

Howard was jailed for his firm refusal to take up arms during the Second World War. The Scotts are not at all conventionally religious; Howard had refused baptism as a boy. But while Howard is confined to a prison camp, his beloved Ruane sends him step-by-step instructions for making a violin (instructions appearing in multiple letters that baffled the government censors).

Ruane also writes this to Howard, presumably in reference to revolutionary nonviolent love:

Our weapon is the smallest possible. Nobody can find it. Even with all their brainpower and ingenuity the task would be impossible. The effect of the weapon is visible and traceable, but the weapon itself is never found. In an age of swords, its effect is peace, joy, frankness, and faithfulness to what is holy. No other weapon can compare to it. It melts ice, spreads lift, brings warmth. It creates and alters, drives out doubt and despondency, and stands guard. It marches victoriously through locked gates, so that he who sits in prison finds consolation.

Sentilles lets this remarkable statement speak for itself. It speaks volumes.

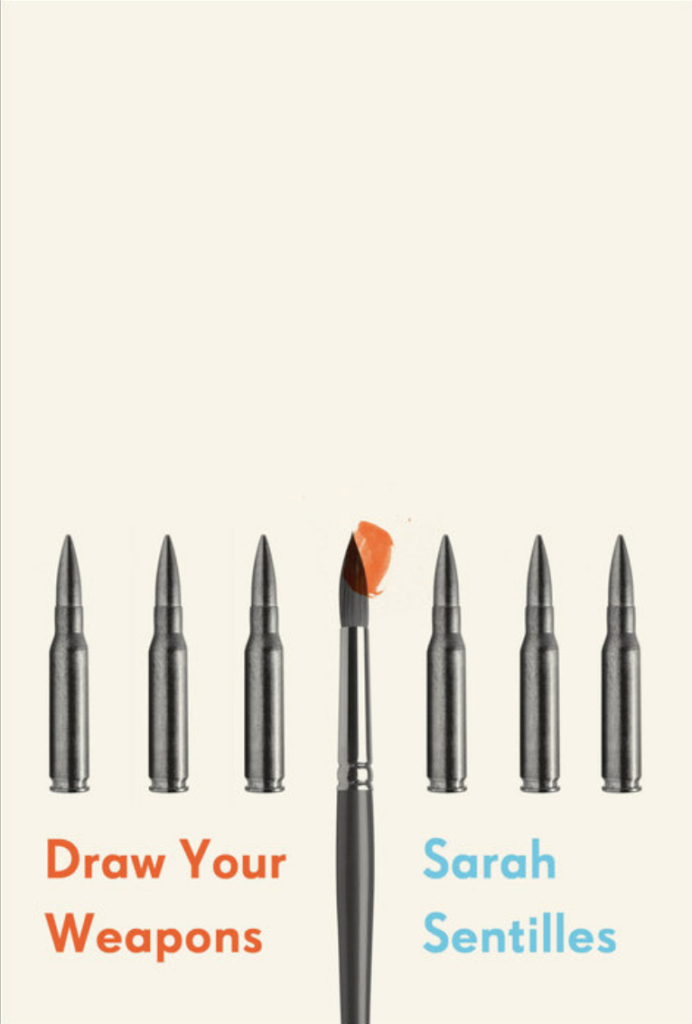

My only regret about this terrific and troubling book is that Ruane’s letter is apparently what inspired the book’s unfortunate title, “Draw Your Weapons.” The artwork on the book jacket—a paintbrush situated in the middle of a row of bullets—shows that the title is meant to work as a play on words, but in my view this play doesn’t quite work.

Don’t be put off by this. Get the book, read it, live with it. It won’t let you go.