The Civil Rights Movement, narrowly defined as Southern-based protest activity that took place between 1954-1968, is considered a watershed moment in American history. Due to the indomitable courage of everyday people who, in the words of Fanie Lou Hamer, were “sick and tired of being sick and tired,” state-sanctioned segregation was dismantled and racial barriers were broken. And as a Southern-bred, thirty-something, African-American professional, I am admittedly privileged to stand here today because my foreparents refused to bow.

Nothing speaks to this truth more than the election of Barack Obama. The incessant juxtaposing of Obama with Martin Luther King, Jr. in the public sphere reveals just how much Americans are aware of this reality. From bootleg t-shirt vendors to professional pundits, the King-Obama correlation has become the racial motif of the moment. And, according to some, America has even “fulfilled the Dream.” From this perspective, it would appear that President-elect Obama has become the concluding chapter in the prevailing narrative of civil rights heroism that has come to define the ways Americans think and talk about the many layers of race in America.

But what happens when we complicate the narrative? How might our conclusions about President-elect Obama’s successful candidacy differ if we resist reifying the civil rights movement as a historical meta-narrative of racial inclusion but rather interpret the objectives of the movement in their appropriate historical context? For those who were legally denied political, professional and educational opportunities due to the color of their skin, access by means of desegregation became the goal.

The prevailing belief at the time was that, if given the opportunity, African Americans would seize their piece of the American pie. Less thought was given, however, to the inextricable link between race, class and gender. And even less to the ways the black elite would become a part of the managerial class of bureaucratic institutions of social maintenance that concretize racial hierarchies.

Thus today we find ourselves at a complicated moment in regards to race. We know that the tentacles of racial injustice have systematically extended themselves throughout the political economy. De-industrialization, the burgeoning prison industrial complex, property-tax based public school funding and the predatory mortgage industry all disproportionately impacts black and brown Americans.

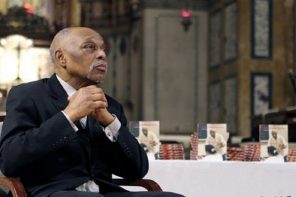

And since African Americans occupy managerial positions in each of the aforementioned areas, I am not sure the language of the civil rights movement is necessarily applicable in combating such multilayered and technocratic forms of racial discrimination. As philosopher Eddie Glaude suggests in his latest book In A Shade of Blue: Pragmatism and Politics of Black America, we must move beyond traditional vocabularies of struggle in order to assess and offset contemporary and complicated modes of racial injustice.

In a post-Obama era, we cannot allow the protest language of those who lived in a segregated society to conceptually flatten or intellectually seize the creative capacity of the post-civil rights generation. If we simply appeal to Martin, bus-boycotts, the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and lunch counter sit-ins, the hyper-visibility of African Americans in places of prominence will undercut protests against racial injustice. Rather we must build upon and move beyond the efforts of the civil rights generation without letting their successes obscure our ever-present challenges.