Consider for a moment this chilling hypothetical. Imagine that the day after last summer’s white nationalist rally at the University of Virginia, the leaders of the group that marched through the Charlottesville campus shouting racist and anti-Semitic slogans take themselves instead to the university’s student activities office. There, they seek to register themselves as a recognized student club, the White Christian Alliance. They submit a proposed constitution for their organization that contains, explicitly framed as a matter of religious conviction, the requirement that all members be white Christians.

If this happened today, university authorities would undoubtedly respond by citing Virginia’s “Contracted Independent Organizations” policy, which makes ineligible for official recognition any student group that “restricts its membership, programs, or activities” on the basis of any of a wide range of protected identities, including race and religion.

So far, so good. But now imagine that a bill that Congress is currently considering to reauthorize the Higher Education Act has become law. Under the terms of the bill, Virginia would no longer be able to bar the White Christian Alliance from campus. That’s because the bill prohibits public institutions of higher education that receive federal funding—which is to say, all (or nearly all) public two- and four-year colleges and universities—from denying “to a religious student organization any right, benefit, or privilege… because of the religious beliefs, practices, speech, membership standards, or standards of conduct of the religious student organization.”

In short, the bill, which goes under the name of the “Promoting Real Opportunity, Success, and Prosperity through Education Reform Act,” or “PROSPER Act,” seeks to enact a particular, and historically peculiar, conception of religious freedom that has in recent decades become a staple of conservative Christian political activism. (The bill itself is primarily concerned with federal financial aid programs, but in addition to what it says about religion, it also contains controversial provisions about campus free speech zones and sexual assault reporting requirements.)

As The New York Times reported last Friday, buried deep within the bill’s more than five hundred pages are provisions that carve out broad exceptions for religious actors within the higher education landscape. Beyond the requirement that public institutions recognize religious student organizations notwithstanding the content of their beliefs or practices, the bill grants exceptionally wide latitude to religious colleges and universities as well. The bill prohibits any “government entity,” whether the Department of Education or an accrediting body that receives federal funds, from taking action against a religious institution of higher education if that action “has the effect of prohibiting or penalizing the institution for acts or omissions by the institution that are in furtherance of its religious mission or are related to the religious affiliation of the institution.”

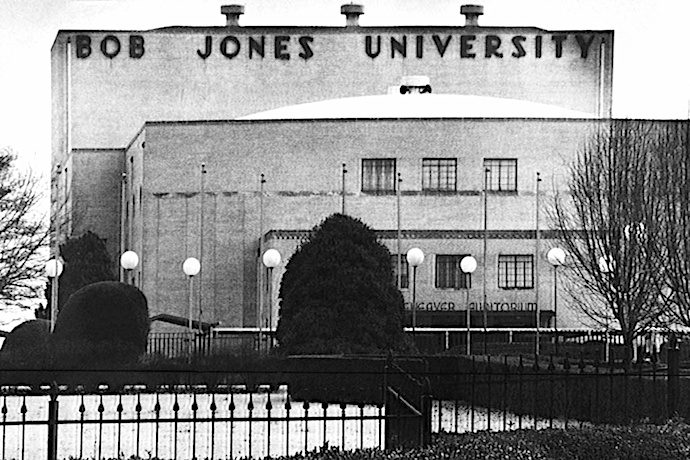

What sorts of “acts or omissions” might the bill’s drafters have in mind? To take one of history’s more extreme examples, in 1970 the Internal Revenue Service revoked the tax-exempt status of South Carolina’s Bob Jones University because it had barred from admission first black applicants and, later, anyone who supported interracial marriage. The Supreme Court subsequently upheld the IRS’s decision in an 8-1 ruling, on the grounds that the agency had acted to further the government’s compelling interest in minimizing racial discrimination. But under the PROSPER Act, so long as Bob Jones could explain how its admissions policies reflect its Christian identity, the IRS could not have penalized it in the first place.

As Times reporter Anemona Hartocollis noted, the PROSPER Act would likewise shield a religious institution from federal penalties if, in the face of some statutory requirement, it barred students from engaging in same-sex relationships, or if it violated Department of Education regulations about the handling of sexual assault allegations, so long as the institution could justify its actions in terms of its religious mission. The bill defines “religious mission” very broadly, saying that the term “includes an institution of higher education’s religious tenets, beliefs, or teachings, and any policies or decisions related to such tenets, beliefs, or teachings.” (A later section of the bill specifically shields religious institutions from the effects of losing accreditation for reasons related to mission.)

The drafters of the PROSPER Act appear to be embracing a theory of religious freedom that seeks to exempt religious individuals and institutions from generally applicable laws and regulations. It is a theory of recent pedigree. Beginning in the 1990s, Christian advocates began to seek in the religion clauses of the First Amendment, which historically had been employed to shield less popular religious groups from discriminatory treatment, protections for their own beliefs and practices. Cases on subjects ranging from school prayer to Ten Commandments monuments to public support for parochial schools have produced a messy and sometimes inconsistent jurisprudence. But in the past decade, as conservative believers have become increasingly inclined to view major public institutions as opponents rather than allies, the most fraught clashes have had to do with the advisability, and the constitutionality, of religious exemptions.

In recent years, the Supreme Court has tended to hold that religious convictions, however sincere, cannot be used as a shield against reasonable actions by government that are not specifically targeted at believers. In 2010, the Court upheld a policy at the University of California’s Hastings College of the Law that barred from official recognition a religious student group, the Christian Legal Society, because the society excluded from membership anyone who would not sign a statement of faith and live in accordance with moral guidelines that included a prohibition on “unrepentant homosexual conduct.” Under the proposed PROSPER Act, of course, Hastings could not require a religious student organization like the Christian Legal Society to meet its “all comers” standard for achieving official recognition, even though it could continue to enforce that standard with regard to non-religious groups.

Related issues have arisen outside the higher education context. The Supreme Court is currently considering a widely publicized challenge to Colorado’s antidiscrimination law by a baker who on religious grounds refused to create a custom wedding cake for a same-sex couple. Previous arguments of this sort, whether raised by bakers, photographers, or florists, have not gained traction in lower courts, although the justices seemed sharply divided at December’s oral arguments in the Colorado cake shop case. However the Court rules, it is clear that religious exemptions will remain a matter of legal and political controversy for years to come.

It’s unclear whether every component of the PROSPER Act’s radically reimagined conception of religious freedom will ever become law, since they, along with other controversial provisions, will likely be tempered by moderates in the Senate. Nevertheless, such sweeping religious exemptions are reckless. They disregard the potentially disastrous consequences of forcing public institutions to accept all religious organizations and of permitting religious institutions to avoid government scrutiny merely by invoking their mission. And by casting such a wide net, the bill forecloses in a thoughtless way one of the most important debates that a religiously pluralistic society can have.

If the PROSPER Act were to become law and the University of Virginia forced to recognized the White Christian Alliance as a student group, how could there still be room for legitimate and nuanced disagreement about the rights of religious believers and their institutions when they come into conflict with our constitutional guarantee of equal treatment under law?