In this series for RD, I’ll be discussing books, both old and new, fiction and nonfiction, that question religion, wrestle with God, and throw down the gauntlet to church and temple. The books I choose will be controversial, radical, provocative—but they will also occasionally rush to the defense of the divine, or take up the cause of ecclesiastical establishments (in which case they will receive a fair, but unsparing treatment).

Why “Devil’s Bookmark”?

Art has long been placed in a unique field of tension, tugged in one direction by the ordering, clarifying, rational principle, while at the same time gravitating toward the unbounded, subversive, and eccentric. Nietzsche famously named these poles the “Apollonian” and “Dionysian”; or “divine” and “demonic,” in a parallel context. Since the Romantic period, the Dionysian, and by extension the Satanic, view of art has been on the ascendant—the artist is seen as both divinely inspired and possessed by an “ungodly” ruling spirit.

To inaugurate this series, what better book than the one I am about to discuss, a novel that fashions “the fallen angel” as a culture hero of the first order…

___________________

It’s been over a decade since the final installment of Philip Pullman’s subversive fantasy trilogy was published, with no new work in sight. So what are devotees of Oxford’s Rebel Angel to do? Well, they could do worse than to remember an old hand at religious satire: Anatole France.

I can hear the sound of collective head-scratching. Indeed, while my local big-box bookstore doesn’t carry a single one of his titles, this Nobel Prize winner (for literature, 1921) is among the world’s greatest satirists. He is also the writer of a clever piece of speculative fiction, Revolt of the Angels (1914), that comes across a bit like Pullman—drunk on sacramental wine.

Satan as Patron Saint of Art

Anatole France extends the 19th-century Romantic view that we owe the very things that make life interesting—from sensual pleasures, to love of freedom, to intellectual pursuits and the arts—to the agency of demonic forces.

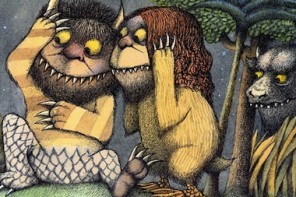

In common with Philip Pullman (who he preceded by a century), Anatole France depicts the ruling God in heaven as a vain, petty, capricious, and boorish pretender, while Satan provides humans with the essentials of inspiration, creativity, learning, and joy.

Thus, we read that it is the fallen angels who, taking pity on humanity “breathed into their hearts the love of beauty.” France here modifies the Christian slander that the gods of antiquity were nothing but a bunch of fallen angels—by turning the tables in an exercise of religious one-upmanship:

in fact we became gods in their sight, and they called us Horus, Isis, Astarte, Zeus, Cybele, Demeter, and Triptolemus. Satan was worshipped under the names of Evan, Dionysus, Bacchus. And the vine-dressers, all daubed with lees of wine, standing up in their wains and bandying mockery or abuse with the passers-by, invented Tragedy.

Satan and his followers bring all the goodies—from wine to Tragedy (with a capital T)—whereas the force conventionally considered to be the fount of goodness and love turns into man’s enemy.

This is where Revolt of the Angels takes a turn toward Gnosticism. For those unfamiliar with that belief system (treated as a heresy by the Christian ecclesiastical authorities), Gnosticism lays stress on the fallen, imperfect, and outright nasty aspects of life on Earth.

For Gnostics, the world as we know it was not created by an all-good, all-powerful, all-knowing, and eternal deity, but rather by a beastly, malevolent bully by the name of Ialdabaoth. There is nothing subversive, per se, in Anatole France’s incorporation of some basic tenets of Gnosticism in his novel. Where it veers toward apostasy is when Revolt’s narrator informs us that the deity Christians pray to, i.e. Yahweh, is in fact none other than the demiurge Ialdabaoth in disguise.

“I believe in the God of the Jews and the Christians,” says a guardian angel who has joined in the revolt against Heaven. He continues in a blasphemous vein: “But I deny that he created the world. […] I no longer believe him the only God. […] And, to speak candidly, He is not much of a god as a vain and ignorant demiurge. Those who, like myself, know His true nature, call him Ialdabaoth.”

Misotheistic Comedy

This is neither atheism nor agnosticism: the one term of religious dissent that sticks in this situation is misotheism, or hatred of God. What is interesting to me is the fact that Anatole France’s hatred of God (what I call an absolute misotheism, because it seeks to destroy God rather than wrestle and quarrel with him) is happily wedded to benevolent Satanism. In this regard, France is more unafraid of ruling orthodoxies than any of the other misotheists I have studied. He can do this under the guise of satire, which fits his discourse rather like a jester’s motley outfit.

Indeed, there is much fun to be had in Revolt of the Angels. One of the book’s most humorous premises is the idea that guardian angels can chose to incarnate and take human form whenever they want to. In the novel, the guardian angel of Maurice (the protagonist) chooses to incarnate precisely at the moment of his charge’s illicit love-making, causing some understandable embarrassment.

When the angel, Arcade, proceeds to seduce Maurice’s lover on his own, our hero challenges him to a duel. As can be expected, the immortal duelist has a rather unfair advantage over his human adversary on the dueling ground. Having your own guardian angel run a sword through you can hardly be topped as an instance of hilarious irony, and it exceeds in daring, I think, Pullman’s irony of inventing homoerotic angels in His Dark Materials.

But, underneath all this farce, there lies considerable seriousness.

Anarchist Underpinnings

Anatole France himself was a sharper and more impatient critic of religion than would be compatible with the label agnostic (which is commonly applied to him). In fact, France in his later years became a fierce anti-theist who compared man’s belief in a benevolent and all-powerful God to a dog’s view of his master.

And since France was an anarchist sympathizer, he was out of patience with any kind of centralized authority; hence his disdain for Yahweh. But he also viewed any form of social stratification with a jaundiced eye; hence his spoofing of the angelic hierarchy.

Revolt of the Angels reminds us that the Christian angelic hierarchy is composed of different spheres or “choirs” (depending on what theologian one follows), with Seraphim and Cherubim at the top, Principalities and Archangels constituting the middle class, and Guardian Angels as the working class of angels. France has considerable fun with this social ranking by having members of the angelic bourgeoisie (the Archangels) foment political revolution in heaven with methods taken straight out of the anarchist playbook, while the revolution’s foot-soldiers are depicted as angelic lumpenproletariat (literally so, as Maurice clothes his guardian angel, Arcade, in the rags, lumpen, of a suicide).

Dense Fumes of Theology

As in His Dark Materials, the plot of France’s Revolt of the Angels is motivated by plans to overthrow divine tyranny and to establish a liberal, constitutional political order in heaven in hopes of bringing just government to all corners of the universe.

In Pullman’s story, this idea plays out as a republican quest:

this is the last rebellion…. This is the greatest force ever assembled…. The Kingdom of Heaven has been known by that name since the Authority first set himself above the rest of the angels. And we want no part of it. This world is different. We intend to be free citizens in the Republic of Heaven.

Anatole France’s angelic rebels against God pursue a similar objective:

We shall carry war into the heavens, where we shall establish a peaceful democracy. And to reduce the citadels of Heaven, to overturn the mountain of God, to storm celestial Jerusalem, a vast army is needful, enormous resources, formidable machines…

But here is where France’s pacifism asserts itself, with a very different result compared to Pullman’s story.

What we get instead of a renewed battle in heaven is merely Satan’s dream of that battle. In this hypothetical scenario, Satan puts God’s forces to rout. After a titanic struggle with much firing of prehistoric weaponry, God’s armies are eventually defeated. The new “elect,” i.e. the leaders of the new dispensation “saw with ravishment the Most High precipitated into Hell and Satan seated on the throne of the Lord.”

But things don’t take a happy turn after this propitious outcome. In fact, Satan dreams that the trappings of his new office almost instantaneously corrupt him. No sooner is Satan installed on God’s throne, than he begins to imitate the attitudes and decrees of his predecessor:

And Satan found pleasure in praise… Satan, whose flesh had crept, in days gone by, at the idea that suffering prevailed in the world, now felt himself inaccessible to pity. He regarded suffering and death as the happy results of omnipotence and sovereign kindness. And the savor of blood of victims rose upward towards him like sweet incense. He fell to condemning intelligence and to hating curiosity… Dense fumes of Theology filled his brain.

At this point, pacifism joins hands with anarchism: Power always corrupts, and it corrupts both the best and the worst in equal measure. But if this is so, how can radical socio-political change be brought about?

Once Satan wakes up from his prophetic dream, he knows what to do. First, he calls off the military campaign against heaven because he realizes that “war engenders war, and victory defeat. God, conquered, will become Satan; Satan, conquering, will become God.” Next, Satan offers the quintessential anarchist advice to those seeking revolution: “We were conquered because we failed to understand that Victory is a Spirit, and that it is in ourselves and in ourselves alone that we must attack and destroy Ialdaboath.”

One can substitute “the bourgeoisie” or “capitalist hegemony” for “Ialdabaoth” and still get the same anarchist idealism; i.e. that revolution can only succeed if it begins and ends with reforms in the mind.

Lusty Angels and Lesbian Grape-Pickers

Not only are there some pretty subversive political premises in this tale, but also plenty of sex and drugs.

Angels are shown to be lusting after terrestrian females: “No sooner do they [the angels] touch the earth than they desire to embrace mortal women and fulfill their desire.” France’s transgressive narrative further celebrates mind-altering substances—especially in the oenological form:

Hail to thee, Dionysus, greatest of the Gods!… I drink to thee who wilt restore the Golden Age, and give again to mortal men, who will become heroes as of old, the grapes which the Lesbians used to cull… and the juice thereof shall be divine, and men shall grow drunk with Wisdom and with Love.

Finally, the various risqué aspects of this story are held together by a nonconformist spirit of misotheism, albeit a misotheism that remains ultimately hostile to any form of top-down government, even to denying Satan the opportunity of usurping God’s throne.

There is much more to this story than I have been able to discuss in the brief space of this post. For instance, France’s overview of the gods’ impact on the history of Western civilization from the Greeks to the present (chapters 18-21) is an unparalleled tour-de-force of anti-theistic debunking. But I want to leave some fields untilled to reward those curious readers who will want to peruse the oeuvre for themselves.

Although—to borrow the lingo of my students—“this book rocks,” it also has its shortcomings. For one thing, it is a curiously unbalanced novel, with creepers of subplots wilting off before they flower, with fizzling theological debates, and with an ending that is a bit too smug to convince. And, unfortunately, in the edition of the book that I used (published by Wildside Press), the text is riddled with egregious typographical errors.

But these are manageable shortcomings in a work that delights the senses, that is wickedly funny, and that illuminates the perennial question of why God—or the gods—cannot be easily reconciled with human notions of morality. Yes, this is an “old” book, but on reading it side-by-side with Philip Pullman’s contemporary works, it not only holds its own, but positively delights with its boldness and its vision.