What inspired you to write Dangerous Games?

In the preface I’m very candid about my experiences growing up in Texas and being told that my favorite hobby is satanic. When grown-ups told me that playing Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) was going to drive me insane or cause me to worship the devil, it suddenly dawned on me that adults were fallible: They ran the schools, the churches, and the police, but they didn’t always think rationally or know what they were talking about.

After that, I never saw the social order in the same way again. I became the sort of teenager who has “a problem with authority.” It wasn’t until I encountered the sociology of religion—especially thinkers like Peter Berger—that I could begin to imagine why D&D was so frightening to Christian conservatives in the 1980s.

Religious studies gave me the tools to finally articulate why these games are so engrossing and also why they were so horrifying to certain conservative Christians.

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

I think than fantasy role-playing games really can function like a religion, in the sense that players work together to construct an alternative world in which they can meaningfully dwell. As sociologists of religion know, when people can imagine an alternative world they tend to see the social order differently. Much like religion, these games create a new mental space from which players can look back on the world and their lives from a new perspective.

The converse of this comparison is that a religious worldview can be compared to a fantasy role-playing game: As long as the adherents of the religion “play their roles,” the world of the religion is “real” and does not require empirical confirmation. In making this argument, I do not mean to dismiss religion or cast religious people as childish or delusional. I don’t believe human beings can function without some sort of socially constructed framework through which to understand the world, so we are all playing “games” of one sort or another.

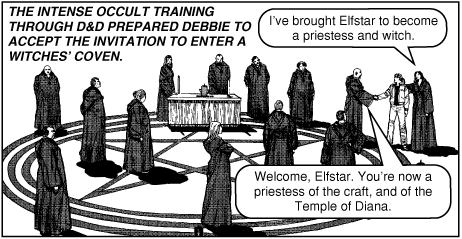

But I do I think this insight helps to explain why role-playing games seemed so threatening to some people. Some of the most ardent crusaders against role-playing games seemed to have been deeply disturbed by the idea that their worldview could actually be a game, no more real than the worlds created in D&D. They never came out and said this, of course, but in their jeremiads about the dangers of these games, they occasionally tipped their hands.

I think the claim that D&D is not a game but an “occult religion” was in part an attempt to push down the nagging sense that reality is socially constructed. In this sense, Christian attacks on role-playing games were actually rooted in a lack of faith on the part of the attackers.

Is there anything you had to leave out?

Surprisingly little. My editors at the University of California Press gave me a lot of freedom. However, there are a lot of really fascinating psychological experiments going on right now concerning religion and the imagination. There was a lot of discussion in the blogosphere this summer about a study published in the journal Cognitive Science suggesting that a religious upbringing affects the way children discern fantasy from reality. Studies like this are easily misinterpreted and we cannot use them to draw facile conclusions about the nature religion. However, I would have loved to discuss this and similar studies in Dangerous Games.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

During the panic, moral entrepreneurs claimed that D&D was an “occult” practice while gamers

countered that it was “harmless escapism.” The problem with this debate is that it makes it impossible to do a serious comparison of fantasy role-playing games and religion. One gamer expressed to me that fantasy role-playing games have nothing to do with religion and that the comparison itself is offensive. But I think this is a useful comparison that allows us to think about both role-playing games and religion in a new light.

Of course D&D isn’t a “religion” in the way that moral entrepreneurs claimed: players are not actually worshipping deities, casting spells, etc. But something about the game made them think of religion and I think it’s worth asking what that was. I also think these games can be a lot more than just “escapism.” I found a lot of cases of gamers who found these games to be transformative: they thought about the world and themselves differently as a result of playing these games. So the point is not to claim that D&D is a religion or that religion is a fantasy role-playing game, but rather to use the creative tension of this comparison to think about how people create meaning together.

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing?

The audience I had in mind was the generation of gamers who were directly affected by this panic. A lot of these gamers grew up to become intellectuals. (It is remarkable how many religion and philosophy professors used to play D&D!) While many remember the panic, its full history has never been properly told. I know for some readers this will be cathartic and vindicating.

Are you hoping to just inform readers? Entertain them? Piss them off?

All of the above. There are two parts to this book. The first part tells the history of the panic from the origins of the fantasy role-playing game in the 1960s until 2001. (The panic never fully died, but 9/11 and the War on Terror gave Americans a much more tangible focus for their fears.) In telling this history I found a lot of information that most gamers never knew about.

The full extent of the panic is simultaneously fascinating, frightening, and tragic. For example, The Committee for the Advancement of Role-Playing Games (CAR-PGa) provided me with copies of documents on how to interrogate adolescent gamers that were sent to police departments throughout the country.

The second part discusses how role-playing games resemble religions and how religions resemble role-playing games. I think that some moral entrepreneurs realized this connection. Their claims that D&D was a religion and not a game were in many ways a kind of defense mechanism that shielded them from viewing their own religion as a game. At the same time, I think that these moral entrepreneurs were fascinated with D&D and that by attacking the game they found a vicarious enjoyment in it. Ironically, many of these figures imagined themselves as heroes who were beset at every turn by demonic forces and evil conspiracies.

Despite my best intentions, some people may find these ideas offensive and feel that either their religion or their hobby has been slighted. But I think most readers will find this book interesting and thought provoking.

What alternative title would you give the book?

For a while my working title was “What The Moral Panic Over Role-Playing Games Says About Religion and Other Imagined Worlds.” I eventually dropped this more provocative title for two reasons. First, I wanted to foreground the importance of play, which is a major theme in the book. Second, I didn’t want the book to be misunderstood as hostile to religion or aligned with the New Atheist movement.

How do you feel about the cover?

I love the cover! It was designed by David Frankel, who attended Hampshire College with me. For those who can’t tell, it’s a parody of the first edition Dungeon Master’s Guide published in 1979. That cover featured a knight and wizard battling an enormous fiery devil that clutched a scantily clad damsel in one hand. (Ironically, the covers of the old D&D books look very similar to covers for some Christian books on spiritual warfare. Both have swords and devils everywhere.) In Frankel’s cover the devil is clutching a rather embarrassed looking middle-schooler, the knight is a soccer mom, and the wizard looks like Pat Robertson. This image demonstrates the irony that the most active crusaders against D&D—those who advanced conspiracy theories involving witches and Satanists—effectively constructed a fantasy world for themselves in which they could embark on heroic adventures.

Is there a book out there you wish you had written?

This book is obviously indebted to Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens in which he outlines his theory that all aspects of culture are developed from play. I also built on the work of Gary Alan Fine whose 1983 work Shared Fantasy: Role-Playing Games as Social Worlds remains the best work on the sociology of role-playing games. Finally, in researching the history of role-playing games I was blown away by John Peterson’s recent work Playing at the World. The history of role-playing games is murky, contested, and a serious challenge for any historian. Peterson did amazing archival research digging up obscure wargame journals and mimeographs from the 1960s and 1970s.

What’s your next book?

2014 was a year with a lot of controversies surrounding monuments. I’m interested in the way monuments are used to inscribe particular histories and ideas of polity onto the land. I’m also interested in the way rituals are used to construct and change those meanings. The connection between ritual, sacred space, and narrative runs through a lot of my work. In my next book I plan to look at some of the controversies surrounding monuments in America in order to explore how and why sacred spaces and sacred histories are constructed.

Photo courtesy flickr user rachel a.k. via Creative Commons