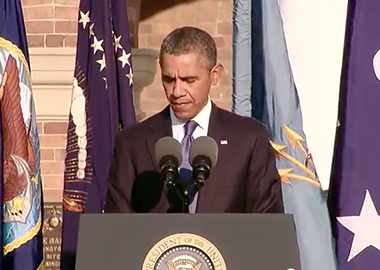

At yesterday’s memorial for the victims of last Monday’s shooting at the Washington Navy Yard, President Obama spoke about the tragedy of gun violence, saying “It ought to obsess us. It ought to lead to some sort of transformation.”

But while the tragedy instantly became national news, with multiple media sources highlighting the death toll of one of the deadliest mass shootings in U.S. history, focus soon turned to profiling the killer. What were his motivations for violence?

Many news stories initially focused on Aaron Alexis’ religious identity: Thai Buddhism. In England, Kristi Kinard of The Times began her piece highlighting what she considered Aaron Alexis’ self-contradictions—he was a former Navy reservist and a Buddhist convert. Al Jazeera America and the Associated Press ran similar stories, remarking on the contradiction between military service and Buddhism.

Perhaps the most explicit of these stories came from CNN. On a live broadcast the day after the violence, CNN anchors Ashleigh Banfield and Chris Cuomo weighed in on Aaron Alexis’ profile, specifically his religious identity. Ms. Banfield explained,

One of the usual things, and I don’t know how this struck you Chris, when I learned he was a practicing Buddhist, when I learned he spent so much time vacationing in Thailand, it was not the profile of the person I would expect to pick up a weapon and kill twelve people in a rampage.

Mr. Cuomo expressed similar sentiments:

Which goes to the legitimacy of being a practicing Buddhist as opposed to someone who was fascinated with Buddhism and maybe hung around with Buddhists, because you know, it is a very defined philosophy, and being someone who has a violent tendencies and appetites does not square with the philosophy involved there.

Misunderstanding Buddhists and Buddhism

What seemed to propel the confusion saturating the media’s initial coverage of Aaron Alexis was the role of religion and, more specifically, the profile on Buddhists. Why would Ashleigh Banfield expect a person of another religion to “pick up a weapon and kill twelve people,” but not a Buddhist?

Over the last ten years, I have looked at the relationship between Buddhism and violence. One of the problems I found is that there has been very little attention to the history of Buddhist-inspired wars, conflicts and violence over the centuries. This lack of information is paired with the vague idea that Buddhists are peaceful, whereas adherents of other religious traditions—most notably Islam—are not.

But whatever people may assume to the contrary, Buddhists have waged violence in Chinese apocalyptic rebellions, assassinated a Tibetan king who would not support Buddhism, promoted and fought in the Japanese-led Russo-Japanese War, Japanese battles in World War II, the Sri Lankan violence in the 26 year-old civil war against the Liberation Tamil Tigers of Eelam, and many more. Although these examples are plentiful, they are not widely known. There are many reasons for this, among them the lack of exposure in most comprehensive accounts of Buddhism. The point here is not to argue that Buddhists are violent; rather, it is to show that Buddhists are people, and that people have violent tendencies [see Monks with Guns: Discovering Buddhist Violence here on RD in 2010].

Currently, there are four charged conflicts that involve Buddhists and Buddhist justifications for violence: over 150 Tibetans have committed self-immolations as a form of political protest; the Burmese 969 proto-nationalist group’s inciting of violence against Muslims; the Sri Lankan Bodu Bala Sena’s anti-Muslim campaign, and; Thai Buddhist vigilante squads and Buddhist military monks engage in southern Thailand’s conflict. Although these tragic events are happening, they appear to have had no impact on initial popular associations of Buddhists. As Joshua Eaton notes in these pages, they lead journalists like Cuomo to falsely disqualify people like Aaron Alexis from their Buddhist identity because of their association with violence—a position that is not held for other religious traditions.

Aside from the misperception about Buddhists through the ignorance of their roles in violence, the bigger problem is a failure to understand the nature of religion and violence. If we aim to understand religion’s relationship to violence and leave one religion out of the analysis, that analysis is, at the very best, incomplete. It also leads to misdiagnoses of violent scenarios—such as the case of the Navy Yard shootings.

How misdiagnoses hurt preventative measures

On April 16, 2007, a massacre occurred on a U.S. college campus—at Virginia Tech. The undergraduate Seung-Hui Cho opened fire on students and killed thirty-two before committing suicide. There was no popular inquiry into Cho’s Christian background and how it might provide justifications for his attacks, even though his suicide letter talked about dying like Jesus.

A few years later on July 20, 2012, James Eagan Holmes entered a Colorado cinema and opened fired on the Dark Knight audience. He set off tear gas and opened fire, killing twelve people. Similar to Cho’s attack, most news stories did not focus on Holmes’ religious identity or how his Lutheran background provided a contradiction to his killing of twelve people.

In the fervor to explore the contradictions implicit in Aaron Alexis’ profile, there was very little attention to the glaring mental health problems and history of violent behavior. Family members have come forward and explained that Aaron had been getting treatment for mental issues. He suffered from paranoia, sleeping disorders, and heard voices. In 2004, he was arrested for shooting out the tires of someone’s car.

All three shooters had a history of mental problems. Seung-Hui Cho was diagnosed with selective mutism and had received mental health services in high school. James Eagan Holmes had meetings at the University of Colorado about his mental health prior to the shooting and he had sent texts to friends alerting them that he might have dysphoric mania. Aaron Alexis thought people were speaking to him through “the walls, floor and ceiling” of the Navy base there, where he was working.

We can look to many other examples, including the Sandy Hook shootings.

Focusing on the role of religion distracts us from more pressing matters. Most importantly, there has been a failure to highlight the role of mental health in violence, and the steep decline in funding for mental health over the last 30 years—since 2009, states have reduced non-Medicaid spending for mental health care by more than $1.8 billion. The National Alliance on Mental Health reported in 2011 that there were wide-sweeping cuts across the nation to mental health services. Just recently, the Civil Service Employees Association (CSEA) announced that New York governor Andrew Cuomo planned to close psychiatric services, including the planned 2017 closure of the Mid-Hudson Forensic Psychiatric Center in New Hampton.

We should indeed be obsessed with ending gun violence; we should also be deeply concerned about how we as a society take care of the mentally ill. Maybe religion will be part of the social transformation the President hopes for, or maybe it won’t. Either way, it’s not the main story here.