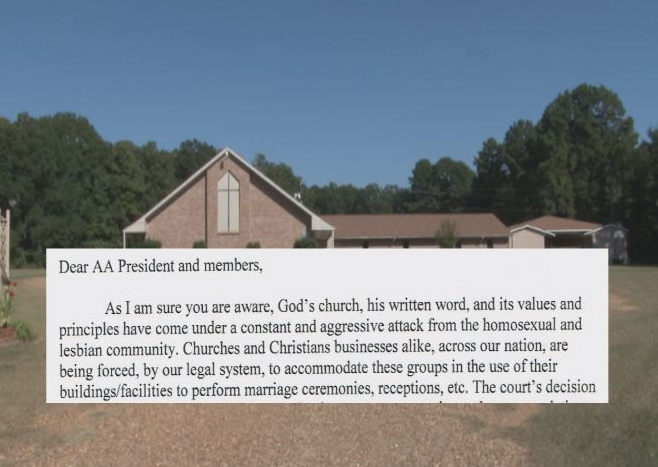

In a story that hasn’t yet been widely picked up in the national media, a Baptist Church in Louisiana has evicted an AA group from its meeting space for fear that because it allows AA to meet there, it could, in some speculative future litigation, be deemed a public accommodation and required to host gay and lesbian commitment ceremonies.

This is going to be catnip for advocates and scholars who make what I call the “sandbox” argument: the argument that we need to allow religious refusals or else houses of worship and religiously-affiliated non-profit organizations (or for-profit businesses for that matter) will take their toys and go home.

The classic example used to illustrate the sandbox effect is Catholic Charities, which stopped providing adoptions in Massachusetts after a law was passed requiring adoption agencies to serve gay and lesbian families. The lesson here is supposed to be that a religious exemption would have allowed Catholic Charities to continue operating and saved the children, in some general pathos-inducing way. This new AA story fits right into that neat little narrative.

The problem is that the story is basically false. Catholic Charities, for example, didn’t close because it was not willing to place children with gay and lesbian couples–in fact, it already had been placing children with gay and lesbian couples. The problem was that once Massachusetts started to consider a law requiring that it do so, the church hierarchy started paying attention, realized that Catholic Charities had already been doing it, and then closed the branch down rather than allow them to continue doing what they had already been doing anyway.

So yes, in some sense Catholic Charities ceased operating because of the law, but not in the way the story implies–not in a way that actually tells us all that much about the impact of religious exemptions.

But the myth of Catholic Charities tells us a lot. The story has been deployed by religious conservatives to advance the idea that broad exemptions hurt the public, an important counterweight to the emphasis on the ways that religious exemptions can harm third parties that have proliferated in the wake of Elane Photography and Hobby Lobby. The truth matters less than the story. And the point of the story is to widen the circle of “victims” impacted by religious exemptions.

Make no mistake, this isn’t just the hasty action of a local Louisiana church; according to the local media report, the church got the idea from a national Baptist magazine article advising churches about how to “safeguard against homosexual marriages.” Apparently the advice was to not let anyone who isn’t a member of the church use the facilities, lest the church be required to let everyone use them.

The banishment of the AA group is the next step in the harm narrative–the widening of the circle of collateral damage caused by any resistance to religious exemptions on demand. If we started with “not allowing exemptions hurts religious believers,” and then moved to “not allowing exemptions hurts people who receive religiously sponsored services when specific services are regulated by law,” we’re now at “not allowing exemptions in one context hurts people who get any kind of religiously sponsored service anywhere else, because it will cause religious organizations to withdraw from social participation and community life.”

From this perspective, the heart of the debate over religious exemptions comes down to who wins the rhetorical battle of harms. We’ve seen in other contexts, like abortion rights, that rhetorics of harm are unstable, and can be co-opted and appropriated to support diametrically opposed positions and policies. The question of who is harmed in the tug of war over religious exemptions–either by the granting of exemptions or by the withholding of them–is live, in flux, and coming to a church basement near you.