Germany has often been lauded for its memory culture and its reckoning with its fascist, genocidal past. “Never again” is both a solemn vow and an integral part of the remembrance culture of the Holocaust, and it has long been a part of the conception of the German state since its unification. Against this background, what’s transpired over the last few days has been all the more shocking.

The recent events in Bavaria—a Southern, very Catholic and quite conservative state—are just the latest evidence of a global right-wing resurgence and should be recognized as yet another warning that a significant shift in German conservatism is underway. It’s also a sign that Germans—many of whom shake their heads incredulously at what they perceive to be the antics of the U.S. far-right—should finally start paying attention to what’s happening in their own country. “It can’t happen here… again” is, unfortunately, nothing more than wishful thinking.

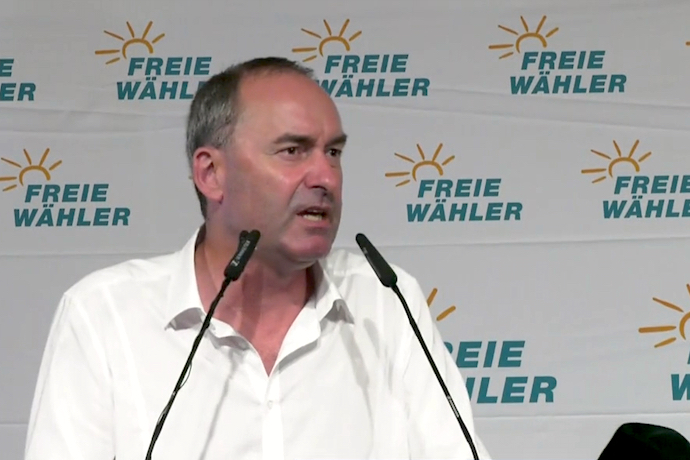

According to the generic playbook of German politics, Hubert Aiwanger’s political career should be over. Aiwanger, Bavaria’s deputy premier, has had an astonishing number of scandals come to light about him in recent days—each of which is so horrifying that any on its own should be enough to result in Aiwanger’s immediate resignation. Or at least, that would be the case if Germany were truly serious about “never again“; if it were a country in which far-right views were shunned.

First, an antisemitic pamphlet, cruelly mocking the victims of the Holocaust, which Aiwanger supposedly wrote as a 17-year-old student, surfaced, and was corroborated by “around two dozen people” who’d been classmates at the time. Then, former classmates reported that back when he was a student the Bavarian deputy premier liked to give the Hitler salute and to spend his time rehearsing Hitler speeches in front of the mirror.

Aiwanger claimed, despite the numerous testimonies of classmates, that the pamphlet was not actually his, but had been written by his brother, Helmut (who has since claimed to be the author of the pamphlet) even though Aiwanger admitted that “one or more” copies had been found in his school backpack. Taking a page from the U.S. Right’s playbook, he asserted that reports about his “youthful indiscretions” were nothing but lies and that the real scandal is how he, the alleged Hitler fan, has been treated by the press.

Meanwhile, the professed author of the antisemitic pamphlet, Helmut, has posted—you can’t make this stuff up—a pamphlet in the window of his gun store recommending Heinrich Böll’s The Lost Honor of Katharina Blum, a novel featuring slanderous press coverage and culminating in the killing of a journalist. The comment beneath leaves no doubt that Aiwanger’s brother knows exactly what he’s doing: “Don’t worry,” it reads, “only Heinrich Böll’s prose ends dramatically.” How funny—a gun shop owner who’s either advocating for the killing of journalists or merely joking about it.

Aiwanger’s statement regarding the accusations against him rang hollow: “The said accusations date back 36 years. I emphasize again, I did not write the pamphlet. I dissociate myself in every form from the disgusting content. I have never been an antisemite, I have never been a misanthrope. I was frightened by the accusations.” That the accusations—not their content—frightened Aiwanger, was telling, and a foreshadowing of the victim narrative he would pivot to only moments later.

Aiwanger admits to nothing—a classic non-apology: “I can’t remember showing a Hitler salute, rehearsing Hitler speeches in front of the mirror.” One would think that someone who had never rehearsed Hitler speeches and shown the Hitler salute would be able to remember this fact perfectly well—and would not have to hide behind a hazy memory. Aiwanger also wouldn’t rule out having made antisemitic jokes:

“I can neither completely deny nor confirm further accusations such as misanthropic jokes from my memory. Should this have happened, I apologize for it in all forms.”

Again and again Aiwanger stresses that much time had passed between the alleged events (which he still hasn’t admitted to) and today—nothing but a silly youthful sin! In Aiwanger’s world, the behavior in question is equivalent to a bad haircut, questionable fashion choices or dodgy hair dyes, rather than allegations that he was a major Hitler aficionado:

“[…] statements have surfaced that give the impression that I was on a misanthropic path as a youth. I also made mistakes as a teenager. I deeply regret if I have hurt anyone’s feelings with my behavior in relation to the pamphlet in question or further accusations against me from my youth.”

Aiwanger continues: “My sincere apologies go first and foremost to all the victims of the Nazi regime, their survivors and all those involved and the valuable work of remembrance.” Anyone who made the mistake after this sentence of believing that Aiwanger had now found his way to the appropriate expression of remorse and humility after all was quickly proven wrong, because Aiwanger went straight to the counterattack—against the journalists who had diligently reported on the accusations:

“However, it is unacceptable that these misdeeds are now being instrumentalized in a political campaign against me and my party. I have the impression that I am to be finished off politically and personally. A negative image of me has been painted in recent days. That is not me, that is not Hubert Aiwanger.”

Instead, Aiwanger presents himself as the victim of a conspiracy: “I am convinced that the ‘SZ’, possibly with the help of other circles, had planned for a long time to damage me massively and to destroy me politically. This was intended to weaken the Free Voters and steer votes to other parties,” he says in an interview with the conservative newspaper Die Welt. He also describes the reporting as “bumbling and a bottomless meanness,” and reinforced the message via Twitter, writing, “Smear campaigns backfire in the end. #Aiwanger.” [sic]

Unfathomably, he seems to be right about one thing: the allegations, reported and fact-checked by reputable journalistic outlets, which should have ended his career as a politician in Germany, have only brought him more support. His party, the “Freie Wähler” (“Free Voters”), have noted a surge in the polls since the scandals broke.

Asked to provide answers to a list of questions about the allegations by his party’s chairman and senior coalition partner, Markus Söder, his responses were so brazen that it seemed an embarrassment to Söder. In response to the first question, “Why were the flyers in your school bag?” Aiwanger’s writes: “I do not remember this process in detail.” Aiwanger answers the second question with a snotty, “See answer to question 1.” Given that he has previously labeled the events from his past “incisive,” Aiwanger can remember surprisingly little about them: “That’s beyond my knowledge.”

Once again Aiwanger portrayed himself as the victim of a sinister conspiracy: “I am horrified how, with a document from my school days and the passing on of information… by a teacher, there are attempts to make me pay, both politically and personally,” writes Aiwanger. He ends with a threat: “The publications from teacher circles are a massive violation of Bavarian service law. Against the suspicious reporting with predominantly anonymous statements and the omission of exculpatory contents I reserve for myself legal steps.”

Aiwanger has acted as if his personal recollection were the only way to reconstruct what happened. For him, the past is mystery, a secret that is impossible to unravel: “In addition, the truth of many allegations can no longer be established beyond doubt. Facts and circumstances can no longer be fully reconstructed. Likewise, interpretation and classification in the situational context is no longer possible.”

One shudders when trying to imagine the “situational context” in which antisemitic jokes, a disgusting flier mocking Holocaust victims, rehearsing Hitler speeches and showing Hitler salutes would be, in Aiwanger’s view, considered extenuating circumstances.

One might suppose that his non-apology, combined with the horrific nature of the allegations themselves and Aiwanger’s failure to apologize and demonstrate remorse—to say nothing of his resorting to conspiracy theories—would be enough for the head of the CSU, Markus Söder, and his senior coalition partner, to cut Aiwanger loose. But Bavaria will vote on October 8th and Söder has made it clear that he intends to continue this conservative coalition—even if it means partnering with someone who has been credibly accused of mocking the Holocaust and imitating Hitler.

And while Söder admitted that Aiwanger’s answers were “not all satisfactory,” they were apparently good enough for the CSU to continue governing with the Free Voters and explicitly with Aiwanger in the cabinet. That may, of course, may have something to do with Söder’s reluctance to look for a new, potentially less conservative, coalition partner. Because, even given the accusations against Aiwanger by various credible sources, researched by several media, there’s nothing worse for Söder and his conservative CSU than a pact with the Green Party. Aiwanger’s crisis communication had not been “ideal,” Söder acknowledged on German TV, but he had apologized and shown remorse. How and when Aiwanger supposedly did that remains Söder’s secret.

This is not unlike the argument made by conservatives in the U.S. who dislike the current GOP but refuse to support Democrats: Presented with a choice between “the Left” and even the far-right, they see “the Left” as the bigger existential threat—and will stick with the Right despite expressions of bigotry, violations of the law, anti-democratic behavior, and more.

Josef Schuster, president of the Central Council of Jews, was not convinced, though his predecessor and president of the Jewish Community of Munich and Upper Bavaria Charlotte Knobloch, holds a slightly different view. While Knobloch, who is a Holocaust survivor, didn’t accept Aiwanger‘s apology, she understands why Aiwanger remains in office and she expressed sympathy for Markus Söder. His decision was “politically acceptable,” she said, because firing Aiwanger would probably have made him even stronger. Söder, meanwhile, who announced that Aiwanger should meet with Jewish communities, added: “but that is the end of the matter from our point of view.”

Just a few days ago both Aiwanger and Friedrich Merz, the head of the allied German Christian Democratic Union (CDU), were in full campaign mode at a local “Volksfest” in Gillamoos, Lower Bavaria, as though nothing at all had happened. Aiwanger gave his spiel to the beer-happy crowd. He ranted against immigration, claimed that there are cockroaches in rolls at the bakery these days (can’t wait until Fox News picks that myth up), and railed against a law that would make it easier and less dehumanizing for trans people to legally change the registration of the sex assigned to them at birth.

In short, Aiwanger went through the right-wing charts of this summer and simply ignored the accusations. In the audience, people held up signs expressing their support, with one man wearing a T-shirt which read “Stand by Aiwanger in times of need, otherwise our Bavaria is dead.” A truly MAGA-esque sentiment where the dear Leader is the only thing that rescues the country—or state, in this instance (Bavaria is kind of our Texas and has more or less openly flirted with secession)—from impending doom and destruction.

Merz followed up neatly and immediately communicated who belongs to Germany for him and who does not: “Kreuzberg is not Germany. Gillamoos is Germany, ladies and gentlemen.” Kreuzberg is a multicultural, artsy, Left-leaning district of Berlin, whose supposed degeneracy Merz juxtaposes with the wholesome homeyness and patriotism of White, rural Bavarian Gillamoos.

Decent, hard-working White country folk, cast as a bulwark of patriotism against the bogeyman image of the debauched, degenerate city people—does this ring familiar?

Communications scholar and media-critic Nadia Zaboura analyzed the breaking of this latest taboo by Merz, noting that in German life enemies are singled out, not only in traditional and social media, but by “the leader of the largest opposition party.”

She goes on to ask: “How does German journalism react to this statement? Does it react? Or has one become tired of the umpteen dam breaks, the same old story, expectable, not newsworthy, no follow-up, this daily applied dose of democracy poison.” Sociologist Nils Kumkar tweeted, “They’re going full volksfremde Elemente now,” while Stanford professor Adrian Daub added: “Oh I see it’s ‘some German citizens aren’t real Germans’-o’clock in Germany again.”

The floodgates have been opened—and they remain open as German conservatism charges full steam ahead, breaking one post-WII taboo after the next.

This article has been adapted from a longer version which was first published in German at “Volksverpetzer”.