The following is an excerpt from Josef Sorett’s Spirit in the Dark: A Religious History of Racial Aesthetics, published in 2016 by Oxford University Press. See Sorett’s answers to RD’s 10Q here.

For all of its revolutionary rhetoric, the Black Arts movement of the 1960s remained staunchly traditional in at least one key way. The novel vision of black spirituality and social life announced in the Black Arts assumed and often explicitly privileged a male and masculinist organizing logic. Ample evidence confirming this fact can be found in two of the movement’s key anthologies. Addison Gayle’s The Black Aesthetic (1970) consisted of 33 essays by some 30 authors, but only two selections were written by women. The proportion of women contributors in Black Fire (1968), edited by Amiri Baraka and Larry Neal, was not much better. If Black Power arts and politics amplified the racial ambitions of the freedom struggle with its nationalist sensibility, it also magnified the long-standing assumption that securing black freedom would involve an enactment of manhood. Indeed, an epigraph borrowed from the poet Margaret Walker was made to authorize this gendered order in the front matter to The Black Aesthetic. The Black Arts, in Walker’s words, was a call to, “Let the martial songs be written, let the dirges disappear. Let a race of men now rise and take control.”

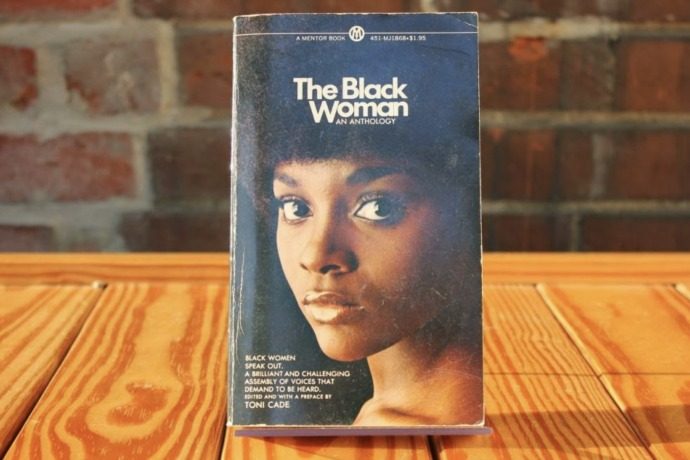

In their representative ambitions, both Black Fire and The Black Aesthetic revealed how the Black Arts instantiated a particular alignment of gender, race and religion. This was especially clear in the appeals of Black Arts men to Islam and Christianity, which were often taken to authorize this gender order as natural or necessary. In their representative ambitions, both Black Fire and The Black Aesthetic revealed how the Black Arts instantiated a particular alignment of gender, race and religion. That Black Arts men could be radical on all things racial and often uncritically conventional in support of a heteronormative hyper-masculinity has been well documented. Ironically, and emblematic of the problem, this configuration took shape even as Larry Neal announced that the Black Arts movement was the “spiritual sister” of Black Power. More often than not, the Black Arts appealed to “an evocation of spirit” that simultaneously obscured and reinforced gender asymmetries. To be sure, the religious performances of Neal and other Black Arts men both invited and received a gender critique. And black women, who were by all accounts active in the ranks of Black Power art and politics, by no means let this spiritualized masculinity go unquestioned. Moreover, religion provided an important pivot around which Black Arts women were able to assent to and dissent from a dominant gender discourse. Toni Cade Bambara’s volume The Black Woman: An Anthology (1970), for example, revealed how a number of black women engaged religion to call attention to the gender politics of the Black Arts.

With The Black Woman, Bambara, a writer, filmmaker and teacher, helped ensure that the contributions of Black Arts women would not be erased or overlooked. Importantly, as Farah Jasmine Griffin has observed, the book brought into conversation two discourses commonly considered to be at odds with one another—black nationalism and feminism. At the same time, the anthology did not entirely overcome the Black Arts movement’s gender troubles. While many of the selections attended to asymmetrical gender relations in black culture, the volume also put on display the investment, albeit an ambivalent one, of many black women in the cult of black masculinity. The Black Woman was not quite the constructive or systemic claim for black feminism of the likes of the soon-to-be-written Combahee River Collective Statement. Ultimately, the anthology complicated and crystallized the power of Black Arts masculinity, even as it offered evidence that a more explicit black feminism was in the making. The Black Woman included offerings from such prominent artists as Nikki Giovanni, Abbey Lincoln, and Audre Lorde, each of whom had prior track records of engaging black spiritual traditions in their work.

Where Larry Neal’s afterword to Black Fire advocated a spiritual integrity styled after the male preacher, Toni Cade Bambara called attention to the shortcomings of that model. Her own essay in the volume, “On the Issue of Roles,” took up the topic of religion both to illustrate the problem and propose some provisional alternatives. In doing so, she appealed to Africa to assert that Christianity was to blame for the current gender crisis. Bambara wrote:

I am convinced, at least in my reading of African societies, that prior … to the introduction of Christianity, a religion fraught with male anxiety and vilification

of women, communities were more egalitarian and cooperative. … There were no hard and fixed assignments based on gender, no rigid and hysterical separation based on sexual taboo.

Bambara’s argument was in keeping with a romanticized reading of precolonial African societies that was popular at the time: that the continent had fallen from an Eden-like state at the precise moment when European colonizers and missionaries reached it with the Christian gospel. The gender problem of the Black Arts was just part of the collateral damage.

Bambara argued that black communities in the United States remained deeply shaped by the colonial legacies of Christianity. Black Arts masculinity was, in this view, an effort to overcome the original trauma of colonization. Even still, it was not to be left unquestioned. She encouraged readers to “submerge all breezy definitions of manhood/ womanhood … until realistic definitions emerge through a commitment to Blackhood.” Although the “metalanguage of race” often served the interests of male privilege, here Bambara advocated abandoning gender talk in favor of a shared blackness. In the face of limited options, the appearance of gender neutrality was to be preferred over distorted definitions of manhood or womanhood.

In bringing together a wide range of voices in a single volume, Toni Cade Bambara’s editorial debut made a singular intervention. The Black Woman directed focused attention to the perspectives of black women, which were all too often undervalued in Black Power art and politics. In this way, the volume was not entirely out of step with the attachment— albeit an ambivalent one—to black masculinity that provided the normative gender politics of the Black Arts. At the same time, Bambara’s anthology largely affirmed the means (i.e., images, myths, symbols) and substance of the revolution, social and spiritual, called for by Black Arts men.

Toni Cade Bambara’s call for a generalized “Blackhood,” rather than a specifically feminist program, echoed an appeal to “spiritual oneness” as a strategy for confronting racial oppression, which was a common refrain across the Black Arts movement. Closely related to this, she also advocated for a turn inward, another idea advanced by editors of both Black Fire and The Black Aesthetic. “Revolution begins with the self, in the self,” Bambara insisted. “The individual, the basic revolutionary unit, must be purged of poison and lies that assault the ego and threaten the heart.” The kind of inward work called for in the Black Arts movement was a new spirituality that sought to address the intramural dynamics of black life on its own terms.

Toward the end of “On the Issue of Roles,” Toni Cade Bambara clarified her push for “Blackhood” over manhood and womanhood. Myths engendered problems as well as possibilities, she suggested. New myths, made for all black people, might also help resolve gender divisions. As with so many others enmeshed in the Black Arts, here Richard Wright’s call—in his 1937 essay “Blueprint for Negro Writing”—for writers to replace preachers and create new myths to orient black life, loomed large. However, Bambara’s interest in myth-making led her to controversial figure from the recent past whom Wright most certainly would not have anticipated: Father Divine. Bambara reminded her readers about this charismatic, albeit unorthodox, religious leader who claimed an audience (all the while claiming to be God) during the same moment that a Harlem Renaissance was in bloom.

Recalling the massive following he acquired, she speculated: “When Father Divine launched his program, the Peace Mission Movement, the first thing he insisted upon from the novitiate was a shifting from male- hood and female- hood to Angelhood. If the program owed its success to anything, it owed it to this kind of shift in priorities.” Father Divine was distinguished, among other things, by his theology of racial transcendence and the Peace Mission movement’s interracial composition. Given the nationalist politics of the 1960s, highlighting Divine—who refused to use the word “Negro” and called for the end of racial classifications—was a surprising move, to say the least. Harlem’s “God” preached nothing that resembled the brand of black consciousness proclaimed by the likes of the Muslim minister Malcolm X or Albert Cleage, C. L. Franklin, and the scores of other clergy who took up the topic of Black Power during the 1960s.

Father Divine was certainly different from most of the models of spiritual integrity (i.e., Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X) celebrated during the 1960s. It must have been odd for readers to find Father Divine on the pages of The Black Woman in 1970, the same year that Toni Cade took the additional name Bambara as an homage to her African heritage. He was not, by any measure, the kind of black messiah typically conjured by the Black Arts. Yet it was there, in her essay “On the Issue of Roles,” that Bambara invoked the positive-thinking preacher as a potential resource for her pioneering black feminist writers and readers. This unexpected connection may have been made possible because Bambara also had access to local knowledge of Divine’s legacy. As a native of Harlem, she had grown up in proximity to remnants of the Peace Mission business empire. She fondly recalled trips with her father and brother to the Peace Barber Shop, which remained in Harlem long after “God” had left the neighborhood. Fond familial memories aside, Toni Cade Bambara and Father Divine were still a strange spiritual pairing. Yet she drew upon Divine’s ministry in a way that was consistent with the larger themes of her anthology. Bambara appealed to Divine to make a case for the equality of the black woman. In the face of Black Power’s masculinist performance, the gender-neutral language of “Angelhood” might help heal rifts between black women and men.

In this way, Father Divine and his Peace Mission movement represented an intriguing alternative to the gender binaries apparent in African pasts, the American present, and, of course, Black Arts mythology. Divine’s turn to a gender-neutral nomenclature to reconstitute community offered an intriguing counter to “hard and fixed gender assignments,” Bambara suggested. Such a shift would be a welcome improvement over gender troubles, which resulted from colonial pasts and continued to frustrate black social life. Toni Cade Bambara encouraged the construction of new myths and the cultivation of a revolution within the self as important methods for dismantling both racism and sexism. In the midst of a “by any means necessary” moment like that of the late 1960s, the allegedly unmarked idea of “Angelhood” made even the unlikely figure of Father Divine a potentially fecund spiritual resource for the Black Arts.