On Tuesday the Supreme Court heard arguments in Holt v. Hobbs, a case about whether a prisoner in Arkansas has the right to grow a ½-inch beard for religious reasons. The media commentary has generally focused, for good reason, on the absurdity of the government’s assertion that a ½-inch beard could be used to hide contraband.

But one of the more interesting threads of the oral argument was Justice Scalia’s assertion that religious directives are “categorical” and not open to a reasonableness analysis. In the first few moments of argument, as plaintiff’s counsel was extolling his client’s reasonableness in asking for just a ½-inch beard to fulfill his religious obligations while satisfying the prison’s security concerns, Justice Scalia opined: “Well religious beliefs aren’t reasonable. I mean, religious beliefs are categorical. You know, it’s God tells you. It’s not a matter of being reasonable. God be reasonable? He’s supposed to have a full beard.”

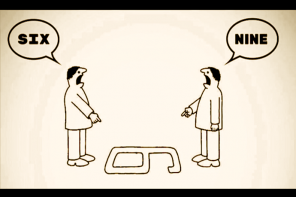

For many, as Scalia recognizes, religious beliefs are categorical. That’s what makes it so difficult to draw a policy line determining at what point we are no longer willing to compromise with a belief that is categorical in nature. (And, by the way, what made it so ludicrous for the Court to rule in Hobby Lobby that the government could extend the non-profit accommodation process to for-profit companies without acknowledging the fact that many for-profit and non-profit companies would continue to object to any accommodation process at all on the grounds that complicity is a categorical sin).

But oddly in this oral argument Scalia seems to delight in this inability to reason with religious dictates. It’s as though it is supposed to make us less sympathetic towards the plaintiff that he is willing to compromise his religious beliefs in order to work with the state on meeting its security needs. The implication is that his very willingness to help reach a satisfactory accommodation is a sign that his dedication to his religion is insufficient to justify an accommodation. Is the idea that only the most inflexible and rigid should be deemed religiously committed enough to receive an accommodation–even though they are those least likely to accept being accommodated rather than absolutely exempted?

In other words, if we require purity of religious devotion we will increase the incentives for claimants to take extreme positions and make compromise accommodations less and less appealing, leaving us more polarized and fractured than ever. That’s a peculiar–and troubling–outcome if the purpose of religious accommodation is supposed to be to allow people of diverse beliefs to live harmoniously together.