The spirit—or ghost, or whatever it is—of William Stringfellow has followed me for quite a ways now. All the while, it comes and goes. I caught it as a college student in Rhode Island from an older friend. It followed me to graduate school in California, where I found myself delivering it onto unsuspecting listeners at an academic conference. Now, unmistakably, it has followed me to New York City, where I keep discovering people who knew the man.

It has followed them longer. Now in his mid-eighties, Fr. Daniel Berrigan’s eyes grew wide when I told him the other evening whose shadow had been following me. In 1970, the priest-poet Berrigan was arrested by the FBI while hiding at Eschaton, the property in Rhode Island where Stringfellow lived with his partner, Anthony Towne. “Did you know this fellow is interested in William Stringfellow?” he kept asking people about me as the night went on, as if he also had seen the ghost.

William Stringfellow wrote Christian theology and practiced law. He died in 1985. Yes, he lived, theologized, suffered, and welcomed guests to his home together with another man (“almost but not quite not out,” as one of their friends once put it). And yes, in a room full of the country’s top theologians, the great Karl Barth came from Germany and proclaimed over Stringfellow, the sole layperson, “Listen to this man!” What struck me when I first discovered his books was how impossible he seemed. Then a little more than now, the terms for discussion about religion in America were set by George W. Bush’s presidency and its constituency. You were either with the faith-based, Bible-beating “values” or you were against them. Their sense of faith-based values was structuring everybody’s thoughts. As a young searcher in the theater of religious options, I felt constrained by such a choice. But Stringfellow beat his Bible with the best of them. He took it plainly and literally, without the worries of liberal theologians that it was written thousands of years ago and we read it very much out of context. Rather, like the fundamentalists, he never let on that his way of reading the Bible came from anything but the Bible itself. His intention was “not to construe the Bible Americanly,” but rather “to understand America biblically.” Only a fundamentalist could think such a thing possible.

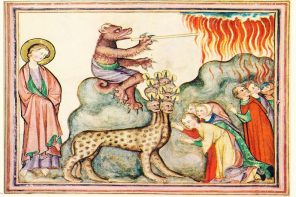

This was what seemed so strange, though: His America is not the city on a hill, it is the beast of Babylon. He wrote fiercely about racism and tenderly about his male partner. For years he lived in East Harlem and defended impoverished people in court. It seemed like, believe it or not, a radically compassionate conservatism. On top of that, he could be funny as hell.

As a student of American religious thought, I know well enough that these ideas don’t come out of nowhere. Stringfellow speaks out of the American social gospel tradition (the most apocalyptic branch), dashed with German neo-orthodoxy and echoes of medieval asceticism. He traded notions with Jim Wallis’ Soujourners, Catholic Workers, and fellow lawyer-theologian Jacques Ellul, among others. But wrestling through Stringfellow’s books, such reductionism has no effect. Their object is something more immediate than their theoretical triangulation. In most, the chapters follow a common course: from death, to hell, to resurrection. The books are little events, little rituals, not permitting what is said to weigh down the celebration of saying it.

Though scathingly critical of religion, the churches, and individualistic “spirituality,” few Americans since Jonathan Edwards have understood so well the urgency of theology. “There is nothing whatever in the experience of men or nations that is not essentially theological,” Stringfellow wrote in a tangent in A Second Birthday, a memoir about the crippling illness that befell him. This could sound like mere apologetics for his medium, which many of us partake in and most of us take with a grain of salt. Try taking it literally, though, and what unfolds is a vision of the whole of social life. Perhaps this is what makes his ghost so inescapable for me: once I wander into it, it comes to seem inescapable for us all.

Take prayer. In their home together, he and Anthony Towne made a great practice of praying, whether for the fate of the world or for the health of their “Christian dog” Marmaduke. Meanwhile, in writing, Stringfellow denies that prayer means asking for something. Nor is it yoga, superstition, or a private conversation, or any of the acts it might masquerade as. “It reveals,” rather, “every connection with everyone and everything else in the whole of Creation throughout time.” He means us to take this bombast at its word. The whole of social life rests on theological imagination, on acts of explicit or implicit worship of what stands beyond ourselves, of what we depend on. The connections we imagine ourselves into with other people and things weave around us with divine thread. By explicitly praying, we reveal these connections to ourselves.

Among “real” Christian theologians, Stringfellow’s greatest contribution may be his writings on the principalities and powers. These entities, mentioned throughout the letters of the New Testament, become the keys for unraveling the heresies and idolatries of modern society. They are all the institutions, ideologies, companies, countries, economies, and religions that command our daily concern. What is so theological about them? Despite people’s ambitions to power, the principalities lie beyond human control. Yet we depend on them, devote ourselves to them, and even die for them. They organize our efforts into horrific wars as well as into marvelous orchestras. Like people, they are subject to the Fall and, in their transience, to death. Writing at the height of the Cold War and the crisis of Vietnam, the principalities that worried Stringfellow the most were American patriotism, racism, and unblinking trust in technology. The principalities are the Bible’s relevance to the daily news. A friend remembers that “wherever he went, Stringfellow had a newspaper in one hand and his Bible in the other.”

This kind of talk can turn the world upside down. We are surrounded by beasts and dragons right out of the book of Revelation, and we fan their flames with our faith. Consequently Stringfellow’s God is not just a character to whom we must defer to for the sake of some future salvation, nor some almighty therapist. God is the means for inhabiting a world filled with mighty principalities and powers. Stringfellow clings to the promise that “Jesus is Lord” because if that is so, there is a reason to love our neighbor no matter what the principalities and powers—from the Pentagon, to “family values,” to the Ford Motor Company—may say. These things are all doomed to death anyway. “Resurrection,” he explains, “refers to the transcendence of the power of death, and of the fear or thrall of the power of death, here and now, in this life, in this world.”

His own answer to the powers came in simple acts. Defending poor black and Latino people in court even though they were not of his clan. And offering hospitality to his friend Daniel Berrigan even when it meant breaking the law. And being with the person he loved, despite the disapproval of society and the churches.

Today, the principalities appear mightier than Stringfellow could have imagined them in his time. We all know the litany: corporations becoming globalized and religions rearing once again for holy war, this time armed with dirty bombs and Predator drones. The world is warming, and the principalities render us helpless to let ourselves stop it. It is sensible to think of these as problems best handled by trained experts in economy, engineering, diplomacy, and the rest. But Stringfellow, who bore no illusions about his own legal profession, knew expertise as a principality too. Because the principalities and powers which govern human affairs are built of theological stuff, theology offers a means to encounter them. Not a dogmatic theology, which becomes a principality of its own, but a poetic and prophetic one.

He hardly set out to solve the problems of the world, and the usual social gospel crowd would fault him this. His problem, rather, was simply “living humanly in the Fall,” amid death and the principalities. Eminent among his solutions was the circus, of all things. He was a lifelong circus fan, and for a time he traveled with a circus as its theologian in residence. Though at his death the planned book on the circus remained unwritten, there are passages among his works that point to its meaning for him. “The circus,” Stringfellow writes, “is among the few coherent images of the eschatological realm to which people still have ready access.” That is, it paints a picture of the world untouched by sin and busy with the enjoyment of love.

Stringfellow was a great basher of idolatries, so I must not be caught being too hagiographic with him. Among theologians he is becoming largely forgotten for sensible reasons. As if to spite the systematic reader on purpose, there are contradictions everywhere. He leaves us with no plan for action, no code of behavior for the modern world, and no school of thought to belong to. These things we have come to expect from our moral theories, and “faith-based” politicians depend on them. There is no proof for the existence of God or that this Jesus really walked on the earth with which to combat the nonbelievers—I may be one myself, but I won’t let it keep me from reading Stringfellow.

What remains is the spirit, the shadow, or the ghost that has been following me for these years from place to place. Though I am beginning to know his aging friends, Stringfellow died before I could have known him personally. In the books, though, he draws us into his circle, mixing anecdotes about himself and his acquaintances in with theological tracts. He seems to offer himself as a friend, one with bits of crazy advice and carelessly-repeated stories. Beneath our cacophonous politics, his pages whisper about how to live in a world both consumed by the power of death and infused in every corner with, for what it is worth, the Word of God.

Tell us what you think! Send a Letter to the Editor at: [email protected]

Icon of William Stringfellow courtesy of C. William Hart McNichols.