Over the past six decades, rock ‘n’ roll music has played a central role in American popular culture. Armed with a fun-loving and rebellious ethos, rock has had a liberating effect on generations of young people and inspired many of their more significant social movements.

Indeed, rock has been so important to American life that its influence has come to rival that of larger and more ancient institutions. One of these, the Church, has responded to this challenge in different ways at different times. After unwittingly inspiring rock ‘n’ roll, Christian forces in the United States demonized, racialized, otherized, and fought the music passionately before trying to wield it to their own ends.

The Devil’s Music: How Christians Inspired, Condemned, and Embraced Rock ’n’ Roll

Randall J. Stephens

Harvard U. Press

March 19, 2018

How did Christians inspire rock ‘n’ roll?

I focus quite a bit on Pentecostalism; especially in chapter one, which focuses on the origins of rock ‘n’ roll. I argue that, in part, the music and the worship styles of Pentecostal churches proved instrumental in inspiring the first generation of rock ‘n’ roll musicians. In particular, you have Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Johnny Cash, James Brown, B.B. King, and others who grew up in Pentecostal churches or attended Pentecostal worship services throughout their formative years. Fortunately, we have good documentation of them speaking about their youth in these churches and about how influential it was for them.

Elvis, for instance, grew up in the congregation of Memphis First Assembly of God, and he talked often about his admiration for the gospel quartets who came through, including the white Statesmen Quartet and the Stamps Quartet, along with African-American groups like the Golden Gate Quartet. Asked by a reporter about why he moved the way he did on stage, Elvis replied simply, “I just sing like they do back home.” And continued: “When I was younger, I always liked spiritual quartets and they sing like that.

Ray Charles, too, was famous for retooling spirituals and black gospel music into love songs and releasing them as secular mega hits.

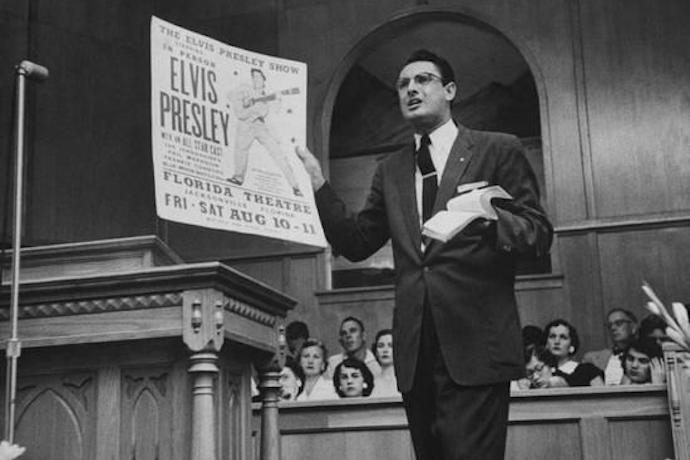

Why then, were Christians so quick to demonize—and racialize—rock?

Betty Friedan identified the Beatles as raising a middle finger to the masculine mystique.

Well, they demonized it, in many cases, because of what they saw as a sort of sinful appropriation. Black and white Christians accused Ray Charles of blasphemy because of how he was secularizing sacred music. Blues legend Big Bill Broonzy certainly believed Charles had gone too far. A former pastor in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, Broonzy claimed that Charles had “got the blues,” but “he’s cryin’ sanctified. He’s mixing the blues with the spirituals.” Or, as the critic Hollie West said about Aretha Franklin, whereas she “once said Jesus, she now cries baby. She hums and moans with the transfixed ecstasy of a church sister who’s experiencing the Holy Ghost.”

There were some white Pentecostals who thought that rock and rollers were thieving from church music. One of these, the Pentecostal youth pastor and author of the Cross and the Switchblade, David Wilkerson, called it “Satan’s Pentecost” and portrayed rock ‘n’ roll concerts as a kind of inverted Pentecostal worship, with demonic speaking in tongues. A lot of this was in the vivid imagination of believers, of course, but it shows that, for many of these observers, there was a thin but important line that was being crossed. In the 1950s, white and black conservative Christians worried that even their church music was becoming too “worldly” or too vulgar.

On the race end of things, because I focus largely on the American South, I looked at the white Southern Baptist Convention, Southern Presbyterians, and Southern Pentecostals, and found that their reaction to rock was almost uniformly negative and very often racialized. They attacked rock as “jungle music,” “congo rhythms,” and “savagery.”

In some cases this is ironic because these are some of the very things that Pentecostals were criticized for themselves—for race mixing and having “debased” music in their services, whether that be Hillbilly, boogie-woogie, or some kind of hybrid black and white styles. So there were all of these interesting, and specific, interconnections that I thought deserved more attention.

Is this racist impulse inherent to evangelicalism? Or southern evangelicalism? Or was it just a sign of the times?

It’s indicative of the times, in a way, because that kind of racist rhetoric about rock and roll also appeared in national newspapers and magazines. But what I found in the case of the American South was that there was often this funny discourse about the missionary enterprise of these organizations—the experiences that their missionaries had had in the field—and how these experiences were supposedly applicable to the music. They referenced the “caterwauling” and the driving tribal drums that they had heard in the jungles of the southern hemisphere, and noted how this had a parallel in the music now blasting out of the mean streets and teenage hangouts of American cities.

So for white fundamentalists and conservatives it took on this different kind of religious dimension. There was also a lot of talk about witchcraft and demon possession—I even remember hearing some of this as a kid in the 1970s and 80s in the Church of the Nazarene. Some of that rhetoric persisted for decades after the 50s.

Why were they so threatened by the Beatles?

In part it had to do with their look, and also with their being from Britain—being foreign. But I think the hard thing for us to wrap our heads around now is that, at the time, the hair length of the Beatles—which they had borrowed from these sort of Beatnik existentialists in Germany—was viewed as such a radical departure from how young men were supposed to look and to behave.

There was a lot of talk about how tight their clothes were and how their hair was effeminate. But most of all, evangelicals, and some Catholics, had a pervasive fear about the hysteria that they inspired in young girls. In all of this, there was this view that teenagers looked to the Beatles as a kind of replacement for religion. And in worshipping the Beatles, they lost interest in the Bible and teachings of the church and the lessons of their parents.

From our eyes today, in 2018, it just looks like they’re these four guys with bowl cuts and these neo-Edwardian, tight collarless suits. But there really was a lot of talk back then about hair styles and comportment and what these meant for youngsters.

I found this great interview from the Canadian Broadcast Corporation from the mid 1960s in which Betty Friedan identified the Beatles as raising a middle finger to the masculine mystique—they were declaring that they had had enough of the crew cut, Prussian-style militarism of hyper-masculinity. So even on the other side of the aisle, there were people who believed the Beatles to be important agents of change.

Timothy Leary, too, made a number of pretty hyperbolic statements about the Beatles ushering in a new religious sensibility—a new way of being for young people. When the four came under the tutelage of the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, it confirmed the worries of many.

Eventually, after a few decades of desperately fighting rock ‘n’ roll, evangelicals moved to appropriate it for themselves. What was the turning point?

I make the case that one important turning point—among a series of turning points—came with a powerful fear about the growing “generation gap.” Conservative Christians became profoundly concerned that their young people were being led astray by worldly influences. When John Lennon claimed that the Beatles were more popular than Jesus Christ, Christians attacked him fiercely, even as they worried that, for the Baby Boom generation, he might have been right.

“If you like Huey Lewis and the News then you might also like DeGarmo & Key.”

They worried that young people were being swept away by rock music and its accompanying celebration of drugs and bohemian lifestyle. As a member of the Missouri Synod Lutheran denomination asked: “when and where and how are local churches giving their 12-to 16-year-old members such markedly special attention that they feel: ‘This is for us’?”

So, in the early years, in 1966 and ’67, young men and women, countercultural Christians, experimented with rock music that had Christian lyrics. Similar innovation had already been taking place in England. In the US, groups like Mind Garage, the Crusaders, or Larry Norman made up the first wave.

Other early bands and musicians included Andraé Crouch and the Disciples, Randy Matthews, the Armageddon Experience, Agape, Sound Foundation, and Honey Tree. Some of these were more awkward and less successful than others, but they all hoped that they could appeal to young people and potentially pull them back into churches.

I remember that, when I was a kid in the early 90s, I once asked my parents for a Vanilla Ice tape and they bought me DC Talk’s Nu Thang instead.

Yeah, by that time there were just all sorts of different versions of Christian rock that followed on the heels of their secular counterparts.

They were always accused of being kind of derivative and lame.

Yes, exactly. And I think there was a lot of truth to that, because when you listen to some of it you find that it’s basically imitative. In 2004 John Jeremiah Sullivan quipped that “Christian rock is a musical genre, the only one I can think of, that has excellence-proofed itself.” Some evangelical and Pentecostal groups even produced charts that were supposed to help teens and their parents find a Christian alternative to a favorite secular band or solo artist. So, you know, if you like Huey Lewis and the News then you might also like DeGarmo & Key. If you like the Beatles or Wings, you’ll appreciate Phil Keaggy.

The evangelicals you document seem to live in a constant state of moral panic. They freak out about Elvis’ hips, the Beatles’ haircuts, Amy Grant’s sex appeal. Why all the anxiety?

Some of it probably has to do with evangelicalism’s eagerness to employ the latest means and technologies and forms of entertainment to appeal to young people, both inside and outside of the church. I think sometimes they have come to think of themselves as in competition with—if not diametrically opposed to—Hollywood and the entertainment industry as well as popular music because they are trying to reach similar mass audiences. It’s little wonder that Billy Graham’s crusades used to air on network television in the primetime slot. He also toured with DC Talk, however unlikely that might seem.

There are also a lot of resentments that fuel evangelicalism. (I’m thinking in particular of Billy Graham’s son, Franklin, and his bellicosity.) I think you can see this in end-times theology as a kind of revenge fantasy in which all of your enemies will get their just desserts. Maybe I’m reading too much into this and the new reality that we live in, but I don’t think it should be too surprising that evangelicals rushed to the side of Trump. He speaks in the same language of the culture war and resentment/grievance that they have harbored for a very long time.

It seems to me, too, that the evangelical commitment to non-stop moral panics has helped to give us Trump. They are constantly identifying social evils that will lead to the end of Western civilization—rock ‘n’ roll, of course, but more recently same-sex marriage, national health care, etc. What can this study teach us about evangelical cultural engagement more broadly?

In the book, I wanted to talk about evangelicalism in a way that went beyond politics, because there has already been quite a bit of focus on conservative Christianity and politics—to a considerable extent, historians care about these religious groups specifically because they are politicized. But a lot of their activity is directly concerned with pop culture and cultural engagement outside of the explicitly political realm. A typical Christian bookstore, with its shelves of Christian kitsch and sanctified consumer goods, definitely fits this pattern.

White evangelical political behavior is just one of many facets of the modern movement. Certainly, it’s an important facet, with 81% of white evangelicals voting for Trump. But evangelicals also define themselves by what kind of goods they purchase, the music they listen to, the kinds of books and magazines they read, etc. I wanted to capture a little more of that aspect.

Has the uneasy relationship between Christianity and rock ‘n’ roll changed either in a significant way?

In the epilogue, I use U2 and Bono to speak more broadly about some of these transformations. The members of U2 were part of the charismatic movement in the 1970s in Ireland, looking across the Atlantic to the Jesus People and to some of the exciting things that were happening—especially California. When you listen to early U2 records now, you find that they are just chockfull of religious imagery.

Surely, the same is true of Bob Dylan’s born-again trilogy of records. Dylan, U2—along with Donna Summer, Van Morrison, Arlo Guthrie, and Johnny Cash—have, or had, a kind of authenticity and a critical reception that Christian rock artists just didn’t have. But groups like that, and other mainstream performers who have worked in some kind of Christian context, have changed rock ‘n’ roll. In them, rock has found faith in ways that it had not before—at least not as overtly.

As for the church, David Stowe and Larry Eskridge have both written about how the Baby Boomers and especially the Jesus People had an enormous impact on Christian worship in America—the style of music that is played, the lyrics, etc. I recently visited a church in Colorado called Flatirons Community Church, and the worship is heavily driven by rock ’n’ roll. The music is extremely loud, and it’s hard to imagine that reality without the earlier experiments with pop culture in the early 60s.