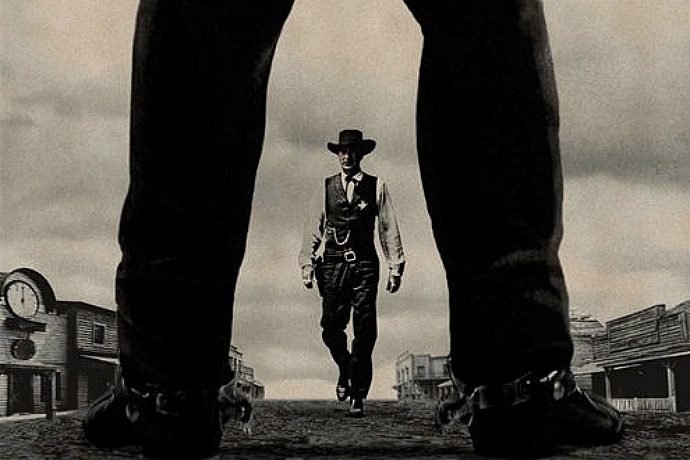

On the windy bluffs of Weehawken, New Jersey, overlooking Manhattan, Alexander Hamilton and Aaron Burr regard one another coldly. In awful synchrony, the pair raise their flintlock pistols, each one squinting down the barrel. Two sharp reports, and Hamilton collapses to the earth. His adversary walks shakily away, clinging to a bloodstained moral superiority.In a flickering cinematic image of another time, a lawman steps out into the dusty main street of a western town. He’s the only man with courage to face down the desperado standing before him. The outlaw goes for his gun, but the white-hatted sheriff is faster. The man in black slowly and bloodlessly slumps to the earth.

It’s one of our most persistent national myths: the duel. Two men face off with deadly weapons. The one still standing proves himself morally superior.

The late theologian Walter Wink famously chided our culture for our “myth of redemptive violence.” It is “the story of the victory of order over chaos by means of violence. It is the ideology of conquest, the original religion of the status quo. The gods favor those who conquer. Conversely, whoever conquers must have the favor of the gods.”

“In quick succession, the raw, unedited smartphone videos gave America something Hollywood has never shown us: a man’s actual death by gunshot.”

This cherished belief has found recent expression in the words of Wayne LaPierre of the National Rifle Association: “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun.” Beneath the smug political slogan shimmers our enduring national myth: the gun’s might makes right.

Until the week of July 4th. That week, the trial-by-combat myth began to unravel in the popular imagination. In the Baton Rouge video, the good guy with a gun fires round after round into the chest of Alton Sterling, an adversary who’s pinned to the ground. In St. Paul, the jittery good guy with a gun, a rising tone of panic in his voice, stubbornly points his weapon at Philando Castile, a man slumped in a car seat who’s clearly not long for this world. In Dallas, the good guys forsake their guns entirely, sending a whirring bomb-disposal robot to reverse its usual mission and blow up the bad guy in a kamikaze attack.

Viral social-media videos thrust the Baton Rouge and St. Paul images into the consciousness of millions. In quick succession, the raw, unedited smartphone videos gave America something Hollywood has never shown us: a man’s actual death by gunshot.

It wasn’t epic. It wasn’t honorable. It was simply horrifying. Far more shocking than even the exploding fake-blood packets of a Quentin Tarantino film.

Hollywood’s cinematic carnage is carefully scripted. The peculiar horror of Diamond Reynolds’ smartphone video, capturing the wheezing final breaths of Philando Castile, was that it was not scripted at all.

Historically, the dueling ritual was widely tolerated in the American colonies. After the birth of our republic, the practice persisted, surviving well into the 19th century. Dueling was even admired as the solemn responsibility of gentlemen: everyone knew what the phrase “meet me on the field of honor” meant. When running for president, Andrew Jackson—who had once killed a man in a duel—did not find that chapter of his biography a liability.

At one time, most duels were fought with swords—which, as far back as the Bronze Age, had been an indispensable part of a gentleman’s wardrobe. Such encounters could be disfiguring, but were not always fatal. The rules of the game allowed for quarter to be given before things went too far. Military historians have observed that dress swords did not begin disappearing from military officers’ uniforms until after dueling had finally been outlawed.

LaPierre’s “good guy with a gun” trope is the direct descendant of the field-of-honor tradition. In the popular imagination of red-state America, open-carry laws allow aspiring good guys to carry on the modern equivalent of buckling on a sword, preparing themselves for trial by combat. They say it’s about protection, but it’s about much more than preserving life and limb. It’s about asserting one’s moral righteousness.

The ritual slap on the face with a gauntlet, the negotiation between seconds, the pacing-out of distance between the adversaries are no more, but Hollywood and the NRA have kept the spirit of dueling alive for generations. Will the brutal cinéma vérité of the smartphone video finally bury America’s love affair with the duel, once and for all?