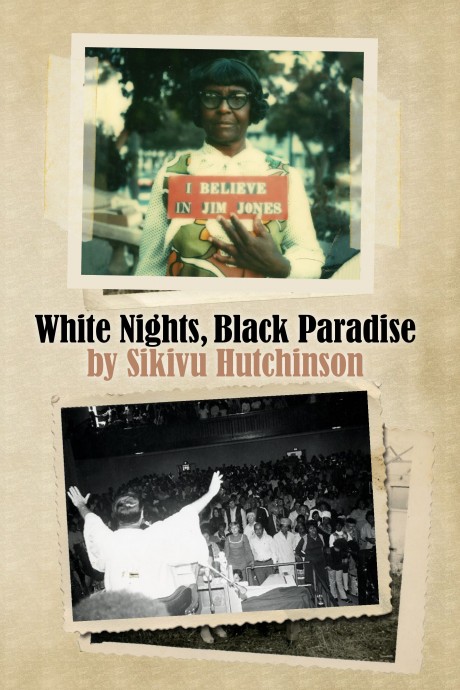

White Nights, Black Paradise, a new novel available from Infidel Books this week, shares a vision of the Jonestown massacre that is rarely emphasized in mainstream literary narratives. One of the largest murder-suicides in modern history has lived on in the popular imagination as a uniquely American tragedy. But the legacy of the People’s Temple is, more particularly, a story of race and religion: 75 percent of the 918 people who perished at Jonestown in 1978 were African-American, and black people—especially black women—were the foot soldiers of that movement.

White Nights, Black Paradise

Sikivu Hutchinson

Infidel Books

(November, 2015)

I recently met with author Sikivu Hutchinson on the campus of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, where she’s currently a visiting scholar at the USC Center for Feminist Research. We talked about the founding of the People’s Temple, why so many African-Americans decided to follow Jim Jones, the “ultimate white savior,” until the bitter, unspeakable end, and what reverberations the tragedy holds for black religiosity today. This is not only Hutchinson’s first novel, but also the first to be written by an African-American woman on the topic.

Hutchinson has long examined the intersections of race, gender and religion, and her other books include Moral Combat: Black Atheists, Gender Politics and the Value Wars and Godless Americana: Race and Religious Rebels. She has previously written for RD on the failed promise of Jonestown’s mixed-race utopia.

The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

__________

What was your motivation for writing a novel on the People’s Temple and the Jonestown massacre?

I wanted to frame the People’s Temple, its social justice trajectory and the initial involvement of African-American women, all the way from its beginnings in the Midwest. I wanted to explore what compelled them to get involved, stay involved and in some instances, go down with the ship.

I see Jonestown as a cautionary tale in terms of why black women are so invested in and indebted to organized religion. I hadn’t seen that in any of the existing literature. I wanted to convey the complexity of their political alignment and the fact that you had African-Americans who were more Civil Rights-oriented, who were coming from the black church, social justice organizing perspective and the Temple represented that aspect for them. And you also have a revolutionary element of secularist, nonbelievers who were disillusioned by the fade-out of the Black Power movement.

I wanted to know how the People’s Temple became validated within black people’s perspectives. Because that’s really what anchored the movement. It was the investment of everyday working-class and middle-class African-Americans but also the investment of black politicians, of black power brokers, of black activists.

You have said that Jim Jones fashioned himself as the “ultimate white savior.” Why do you think he felt this draw to proselytizing African-Americans, black women especially?

Part of his personal lore was that his father was a klansman, and he would tout that as his motivation for trying to align himself with African-Americans—and ultimately even identifying as African-American. He was the first white person in the state of Indiana to adopt a black child. He always had people of color around him in the early days, and he was quite vocal about pushing back against Jim Crow ideology. He was an orderly in a hospital that refused to treat black patients, and he protested against that. He also desegregated several theaters in Indianapolis. He was also very much opposed by the white Pentecostal power structure for bringing in African-Americans.

All those elements were integral to how African-Americans were brought into the movement and why they stayed—because they saw this white man going to the barricades for them, identifying with them, having family members who looked like them and constantly making racial inclusion a part of the superficial cultural propaganda of the Temple. When the People’s Temple moved to San Francisco in the 1970s, black communities were being disempowered and displaced. A lot of parasitic development was going on, and people were being pushed out of the city.

So the Temple was at the forefront of organizing around those disruptions and pushing back, providing programs and social services to the community, needs that African-Americans felt black churches in the Bay Area weren’t meeting. The People’s Temple not only fills the breach created by the decline of the black church—as far as it being a movement organizer in social justice and a provider of social welfare—but also the breach caused by the decline of the Black Power movement and Civil Rights movement.

There was also the family dynamic that the People’s Temple fostered where there would be several generations of a family connected to the Temple. You had all of these elements pushing African-Americans into the movement and anchoring them there—and that made it more difficult for people to leave the movement when all the abuse, harassment, and terrorism was occurring.

Despite the fact that the majority of the People’s Temple membership was black, Jim Jones chose mostly white women for leadership roles. Why did this happen?

Had there been prominent African-Americans who exercised real power in the church, then there would have been a lot more questions raised about the funding apparatus—in addition to the cult of personality that he had developed.

Jones was a predator who preyed on people sexually but also mentally and emotionally. To reel them in there would be the evocation of the benevolent white man bucking the power structure of white supremacy, wholly invested in and identifying with blackness. He’s telling them we’re going to take all these Social Security payments, the property, the welfare benefits that our members are providing as part of their tithing and say we’re building this black nation, that that’s the ultimate goal. This was something that was internalized and accepted by a lot of the African-American members.

You’re careful to never describe the People’s Temple as a cult. Why is that?

It’s a demonizing term. It strips religious ideology of its complexity. It’s a term that relies on a dichotomy where the established religious orthodoxy is correct, and then there’s a certain set of religious beliefs, practices or movements that are somehow corrupt and debased because they are not coming from an Abrahamic tradition. And being an atheist, I question the Abrahamic traditions. Just because those are thousands of years old, just because they’ve been validated by scholars and religious leaders, that does not give them infallibility.

Why has it been so easy for society to erase the memory of race with regard to the People’s Temple, to think of it as more or less a white movement?

The truth of Jonestown has been lost because it’s been demonized to a certain extent. The impression was that you had these “zombie-esque acolytes running over there and bowing down to this white man.” It just creates a very sordid and unsavory picture. Also, it took place in San Francisco, a city that has always been mythicized as a white space. You had a white pastor, so many white bohemian liberal-to-radical members involved quite prominently and that becomes a big part of the ethos. That this is a “free love” church, that it was a new age-y kind of confab, when it’s really coming from the heart of Pentecostal, charismatic spirituality.

Black women were then and still are one of the most religious segments of the population. How is the white Jesus paternal figure they’re presented with in mainstream Christianity different from how Jim Jones presented himself?

The picture was different because Jones was very conscious about articulating his opposition to biblical dogma and rhetoric around the inhumanity of African-Americans and African bodies. He was up front in saying that the Bible is problematic when it comes to enfranchising and humanizing Africans. He was aware of the terrorist past of race relations in the United States, that Judeo-Christian reign within the United States has always undermined black agency and self-determination. So that was the key difference.

He was also very vocal about his atheism, although that atheism was qualified over time. He began to say he was the true god, that he was the real deity and all those others were false deities that were racist and white supremacist. So he presented himself as an antidote to that, saying he loved the black people, he worshiped blackness, he had a black son, he was rooted in the black community with all these black politicians validating him. So he used all this as armor against the claim that he was just another white savior trying to hoodwink these downtrodden African-Americans.

On the other side of the coin, you have the increased visibility of the black atheist community. Is that growth we’re seeing today influenced by the way the Bible was historically used to justify the degradation of black people?

I absolutely think that is the motivation for many African-American nonbelievers. That the whole Curse of Ham lore, the justification of slavery, the justification of rape and commodification of black women’s bodies— all of that plays a big role in the embrace of atheism and secular humanism by African-American women.

I believe that black atheism is expanding and getting more visible, certainly in terms of the virtual sphere. What remains to be seen is whether that is going to turn into anything broad or movement-based as far as African-American nonbelievers and secularists interfacing with other political movements.

Do you feel this moving away from churches as authority figures is represented in the Black Lives Matter movement?

Absolutely, you can see some of that in the “nones” demographic. There’s been an emergence of those folks who are not explicitly aligned with organized religion, aren’t involved in a church, aren’t coming from that traditional background of black church dogma—but who still explicitly identify as spiritual.

Could a tragedy of Jonestown’s scale still happen today?

The seeds of Jonestown are still there underneath the surface and given the grip that religiosity and charismatic spirituality have on scores of people, it could absolutely happen again. The severity of economic injustice and political disenfranchisement that really motivated black folks to get involved, stay involved and in some instances, decide to die, those conditions still exist and could still facilitate that kind of tragedy.

Sikivu Hutchinson will be hosting a talk about White Nights, Black Paradise on the USC campus on November 24th. You can RSVP here.