I recently had the great pleasure of visiting Washington, DC with my tween. With its grand buildings and symmetrical beauty, awash in history, meaning, and hope, the National Mall inspired a sense of pride in the breast of even this guilt-ridden cynic.

I see my emotional response to DC as a remnant of my religious upbringing as an American. For years in public schools I stood with my peers, placed my hand on my heart, and recited the Pledge of Allegiance daily—always fighting the urge to end with “amen”—followed by the singing of “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee.” I learned stories of our nation’s heroes: how the pilgrims risked everything to “discover” a new land for the sake of religious freedom, how the founding fathers stood up against the British bullies, how the North fought against slavery. More recently, I confess an unhelpful addiction to Hamilton, which has reactivated these religious sentiments despite my best efforts to be critical.

The art and architecture of Washington—just like flags and Fourth of July fireworks—are designed to tap into our deepest commitments and longings. They are physical manifestations and reminders of America’s sacred mythology.

And mythology it is. Which is why I was jarred upon my first visit to one of the Smithsonian’s newer additions, the National Museum of the American Indian. It is a subtly gorgeous building, reminiscent on the outside of wind-swept earth and defined inside by undulating curves and a vast atrium. Everything about it has been thoughtfully designed to contribute to its mission of “advancing knowledge and understanding of the Native cultures of the Western Hemisphere—past, present, and future.”

What gave me pause was an exhibit called “Our Universes” about how “traditional knowledge shapes our world,” which included video storytelling as well as clothing, art objects, and household tools. At first this pleased me, in that it started from the understanding that “we” construct “our” universes through a complex interplay of inheritance and choice. Lakota, Quechua, and Anishnaabe peoples, for example, live in distinct universes that have been shaped over time through their various languages, landscapes, and rituals.

But then I tried to imagine such an exhibit anywhere else in the Smithsonian. Our universe makes an appearance at the National Air and Space Museum, but the assumption there is that it is one based on physics rather than “traditional knowledge.” We generally don’t ask what universe the Wright Brothers or Gus Grissom lived in. And at the National Museum of American History, I don’t recall any explanation of “my universe” at Julia Childs’ re-created kitchen; perhaps visitors are presumed to share Julia’s universe, so it needs no explanation? Such differences in treatment are especially troubling given recent complaints of Smithsonian censorship by Native and Muslim American artists.

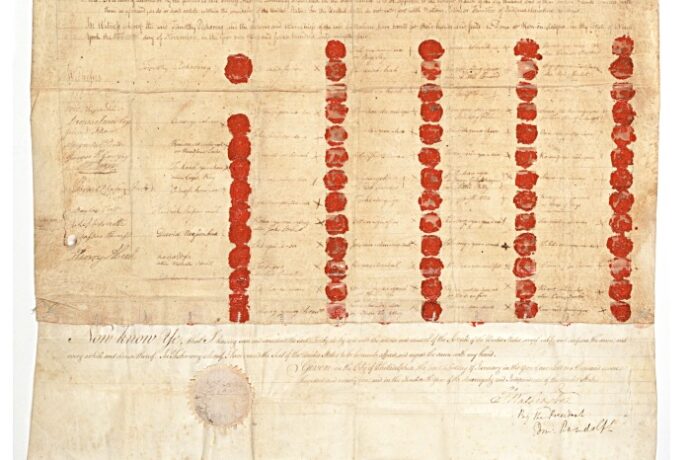

To be sure, a particular “universe,” a sacred mythology, is on display everywhere in the capital. What Lincoln, Jefferson, and King “believed” is written explicitly on the walls of their monuments. A small statue of Eleanor Roosevelt in the shadow of her husband’s giant memorial says a few things about this universe as well. The celebration of American militarism is made manifest in the war memorials and cemetery. The simple fact that there are no buildings taller than the Washington Monument speaks volumes about the universe that DC has created for itself. But in general, an exploration of the traditional universes in which white Americans live is left implicit or uninvestigated, presumably subservient to simple “facts.”

The creation of new museums dedicated to American Indians or African American history and culture is a sign that some part of our civic culture is slowly waking up to the ways that Americans live—indeed have always lived—in different universes, though these undoubtedly intersect and overlap. There is simply no comparing the universe in which I live to the universe of George Washington, or for that matter the universes of Tamir Rice, Dolores Huerta, or Kim Kardashian. I don’t even want to imagine the universe this guy lives in.

But there is always a temptation for human beings to assume that the universe we live in is the universe, the real one, while others live in some skewed fantasy. This can be especially true among those of us who like to believe we have eliminated mythology from our everyday lives, while looking down on those “traditional” people who dare to make their myths explicit. (Sadly, even J.K. Rowling has fallen prey to this type of thinking.)

In this season of American civil-religious self-congratulation, it’s worth reflecting on those stories, objects, heroes, and faith tenets that we usually take for granted. The universe, as each of us knows it, is not simply a fact. Mythology is ours, whether we acknowledge it or not.