“Who do you think you are—to want to be a writer?” These are the words that haunt the young Mormon girl who is the protagonist of Judith Freeman’s new memoir, The Latter Days (Pantheon). Freeman, whose breakout novel The Chinchilla Farm (Norton, 1989) established her as one of the first Mormon writers to gain a national standing in literary fiction, wrote three more novels before turning finally to non-fiction to grapple with her Mormon upbringing. After looking up to her for almost three decades as the rare Mormon woman writer who made it, I interviewed Freeman this week, just in advance of Latter Days’ June 7 release.

Joanna Brooks: I don’t know that there has been a more effective mapping of the subterranean emotional landscapes of day-to-day American religious life than Latter Days. But after so many years writing fiction, why a memoir now?

Judith Freeman: It began with Romney running for president and friends of mine asking, “Who is he?” There was so much that he wasn’t saying about himself, about his religion. I knew that journalists in press conference and even Harold Bloom would never ask the right questions. The questions had to come from within the culture. My friends at the Los Angeles Review of Books came to me and said we want you to write a piece about Romney, to put on paper all of these things you are saying. I tried for months to write that essay. I couldn’t find a tone that was reflective and intimate and nonjudgmental, a tone that wasn’t strident. I couldn’t get it right. But I agreed to collaborate with my editor Laurie, and within a day or two I had managed to sit down and write the piece that became “The Mormon Chronicles,” recalling how my great-grandfather when to jail for polygamy, with his great-grandfather, and leading into stories about my childhood and the church. It was published on the eve of the Republican convention four years ago. It was the first time I realized what blowback you get—I got vicious mail, funny mail; the LARB had never gotten more responses—

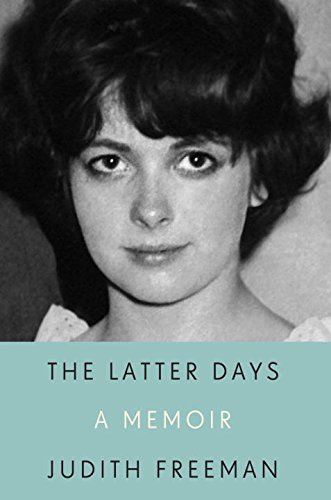

The Latter Days: A Memoir

Judith Freeman

Pantheon

June 7, 2016

Mormon media traffic is intense!

Yes. And when it was all over I thought, I think I would like to write a memoir now, something I’d never wanted to do. I think I found the right tone. And we took it to my editor at Pantheon, and he immediately said yes, this is the book I’ve been waiting for you to write. Go write it. That sequence of events brought me to voice—that’s what is truly important.

How would you characterize the quality of this voice you’ve found?

The first word that comes to mind is frank. It’s a very frank, straightforward voice. It’s a storyteller’s voice. Immediate and direct.

That searching frankness allows you both to talk honestly about choices you’ve made that others might judge, but it also entitles you to find beneath the surface piety of the Mormons around you during your childhood an astounding range of human motivation. This strikes me as enormously important given how Mormons have been caricatured—I think of the Book of Mormon musical, for example—as being extraordinarily flat. Romney was seen that way too. As if there was nothing going on beneath the surface.

All of the people I knew growing up were complex, remarkable personalities. But I think one of the difficulties is that the Church has always emphasized that we should tell faith-promoting stories and put the best spin on everything. I think the consequences of that can be devastating for individuals full of flaws and trying to reckon with their own stories. When I think about the girl I was—I was a thief, I was stealing things, I was having an affair—but in truth I was a very human, flawed, striving, seeking young woman. For a long time, I stole things in my life. And I really had to think about that later. I had to ask myself, “What sort of person does that make me?” In the middle of Latter Days, I write about how stealing anything from anyone makes you feel poor, that as long as you feel you must have something but you can’t afford it, it will forever continue to cement in you this feeling of poverty. Those kinds of realizations can’t come about without frank self-examination.

I do think a kind of want, a hunger, a sense of poverty, some of it perhaps inherited from our ancestors, is a reality for so many women in Mormonism.

Yes. I think there is a lot of desiring and settling for second best. And part of the result is an enormous amount of depression and use of anti-depressants among Mormon women. Men often don’t fare much better. They have unmet desires and shame and secrets that I believe lead to an extremely high statistic of men looking at pornography. There is a price to be paid for hiding things, for keeping parts of yourself secret. A lot of people in Mormonism lead double lives due to the pressure to tell faith-promoting stories.

I think it comes too from the foundations of Mormonism in an open revolt against loss. The ability to do saving rites for the dead was essential to Joseph Smith’s vision. There is no more death-defying religion than Mormonism—death can’t sever marriages performed in Mormon temples; generations can be linked together forever through genealogy. Instead of processing loss together, we bracket it, agree to put it on hold, and be perfect together. But beneath the surface, Latter Days shows, there is cunning, perversity, boredom, cruelty, so little recognized by writers within and without our culture. You have an especially penetrating view of Mormon men, who are so readily characterized as patriarchal—like the rows of Mormon male leaders in their suits and ties one sees when one watches LDS General Conference.

“We live patriarchy with a particular intimacy in Mormonism.”

Looking back was revelatory for me. There are certain moments—for example, receiving a patriarchal blessing, so sacred to Mormon people, which I describe in the book, or being healed by the laying on of hands—when patriarchy is inculcated in the physicality of a moment and then there is the patriarchy you sense when it becomes twisted or tweaked or placed in the hands of someone who is confused or troubled or has his own secret agenda or who simply feels entitled and anointed by his maleness. As I describe in the book, there was the Mormon male boarder who lived with my family, and who tortured me with accusations of moral and sexual impropriety when I was a girl.

We live patriarchy with a particular intimacy in Mormonism. A Catholic priest does not live in your house with you and act as your father, but a Mormon bishop might be your father, a Mormon priest is your brother, an elder is your uncle. The power is inculcated through familiar close relationships. Sometimes in a gentle kind way, but there are many men in the world who love to play this role of intimidating women and frightening girls, and there were some of those people in my ward , and I disliked them intensely. There were hypocrites, and then there are the rosy-cheeked fumbling men who make the awkward suggestion that you are wearing your cutoffs under your dress, like the Mormon male neighbor from my girlhood whom I describe in my book, who have their own longings and are trapped, as trapped as women who have no power. What drew me to want to write novels was this incredible range of human behavior, motivation, and attitude, the deceit, the sense both institutional and private that the community needs secrets in order to function.

How did you learn to live beyond that way of keeping secrets?

It’s a process. I’m still involved in it. So many of those adaptive skills that I learned as a child are ones that I’ve carried with me throughout my life and some of them I would like to shed and some of them have served me very well. In every case it is still with me. It is who I am. It makes it so interesting to try and answer the question, “Are you a Mormon?”

You find that too?

Oh, yes. For many of us it is such a profound question. Many people would think it is a yes or no question. But it is wonderfully complex: what made me who I am and what would happen to that if I defined it without the parts of Mormonism that have always been attached to me. Can I be a feminist humanist secular revisionist Mormon feminist? What am I? It’s a process.

There’s a particularly poignant scene in the book when you’re being wheeled away to give birth to your son. You are so young, alone, and in pain, and you call out demanding to speak to David O. McKay, who was LDS Church President, as if you are asking permission . . .

Not to die! When I went through the turquoise notebook that I kept during my years in high school in my Mormon seminary classes, I look back at all of the worksheets and handouts. There was a handout from President David O McKay saying no one is more sacrificing than mothers and of course it deifies us almost, but nowhere are we more sacrificing than at the moment of giving birth. Bubbling up from that handout is the idea that we are to be self-sacrificing even as we are taken to the brink of death. And this is from President McKay—a lovely, unmacho man—almost feminine. He grew up in a mountain valley outside of Ogden, and my mother talked about him as though he was a very gentle soul. So was I appealing to that side of the Mormon male hierarchy.

This is a book about refusing death, and the price of that is shame.

There’s a lot of shame to work out from under. And you have to be willing to do that hard excavation to get out from underneath culturally and within the family and within the religion a lot of resistance and judgment.

But doing so allows you to bring back a more complex self to witness the girl you were, the young woman you were, the struggle and hunger and humanness that entailed. We need witnesses.. You made it to the outside and you came back to witness. So often, especially when it comes to the lives of Mormon women, I feel that there is no one but us to witness ourselves—and no one to hear us. You hear us.

It has meant stripping away a lot of the stories and half-truths and fearfully-lived constructs that have sort of kept me. Bringing back a more complex self to witness means bringing forth a more mature vision. A woman willing to be generous with her past is a woman who can be generous with herself.