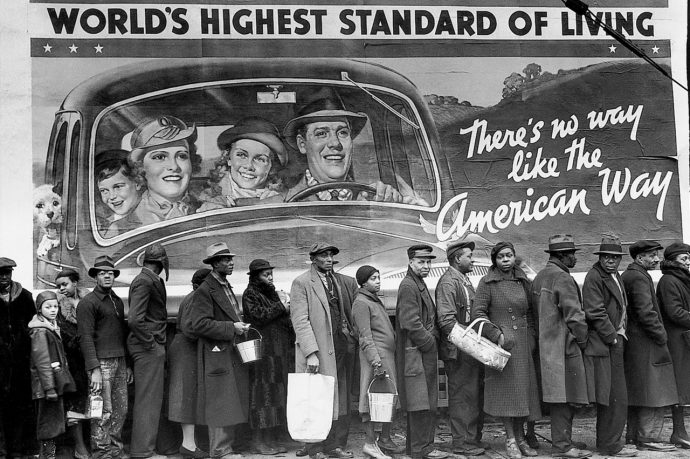

The public debate about how best to address poverty seems too often like a partisan cage match. Political liberals assign responsibility to the state, while conservatives double down on the argument that the private sector—churches and private enterprise—can better relieve the suffering of citizens.

During the 1930s, these competing visions were put to the test in especially brutal fashion. The lessons learned—and the myths propagated—are the subject of a fascinating new study.

Alison Collis Greene is Assistant Professor in the Department of History at Mississippi State University. Her book, No Depression in Heaven: the Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Transformation of Religion in the Delta, tells a story of faith, famine, and the fight for survival in the Great Depression South.

RD’s Eric C. Miller spoke with Greene about her project.

No Depression in Heaven: The Great Depression, the New Deal, and the Transformation of Religion in the Delta

Alison Collis Greene

Oxford, December 2015

Your book issues a corrective to one popular but inaccurate narrative about the Great Depression and those who struggled through it. What is that narrative, why is it inaccurate, and how did it come to be so popular?

The book opens with what I call the myth of the redemptive Depression. I guess you could call it our nation’s welfare origin story. Basically, it’s the idea that the Great Depression really wasn’t all that bad—or it was bad, but from adversity came redemption. People gave up luxuries they didn’t need, turned to their families, their communities, and their churches, and together rediscovered a simpler life and also maybe Jesus.

But then, the story often goes, Franklin Roosevelt took office and put the government to work to end the Depression, and maybe people needed a little help getting back on their feet or maybe not, but either way, he really should have left things alone after a year or two. But he didn’t. So even though the Greatest Generation came through the Depression and WWII strong and self-sufficient, their kids and even more so their grandkids were weak and came to depend on all kinds of extra help from the government.

I think it’s fairly obvious why this narrative is popular. It falls in line with a general nostalgia for a simpler time and with complaints about big government and welfare dependents. And it’s a very comforting story of triumph over adversity.

“Religious leaders—conservative, Southern ones—led the call for federal intervention because they were powerless in the face of suffering.”

But it mostly skips over the adversity, in part because that’s not a fun part of the story, or one people like to remember. The Depression brought the kind of suffering that tore families and communities and churches apart as often as it brought them together. Mothers handed over their starving children to orphanages because they couldn’t feed them; fathers hit the road to look for work and didn’t come home. That local supply chain fell apart in villages and small towns where drought ravaged the crops, falling prices made the rest worthless, and bank failures wiped out people’s savings. The churches that were for many rural people the only place to turn in crisis were broke too.

In fact, I found over and over that religious leaders—conservative, Southern ones—led the call for federal intervention because they were powerless in the face of suffering. They applauded the New Deal, even claimed it as a religious accomplishment modeled on the social teachings of the churches.

You note that, initially, many Southern clergy judged the Depression to be a religious problem with religious solutions—prayer, repentance, revival. They often claimed that the government “dole” posed a more serious threat than poverty. What changed their minds?

They changed their minds for a few reasons: people needed help and churches couldn’t provide it. Calls for revival didn’t bring in either souls or dollars. A widespread critique of capitalism reemerged to characterize suffering as a result of systemic rather than personal failings.

It’s also worth noting that most folks didn’t change their minds entirely. In general, clergy still opposed direct aid to the poor—the dole—because they thought poor people were irresponsible. The New Deal only provided such aid briefly, in limited fashion, and at the discretion of local administrators. Roosevelt instead touted “the joy and moral stimulation of work,” and that was his real focus—work relief was popular among Americans of all classes. Of course, other programs regulated the economy and protected workers, and then Social Security created a social safety net. But it was based on a payroll tax and really a very conservative program.

In many ways, the New Deal seemed to many religious reformers to be an extension of what churches had been doing as they had helped patch together a limited safety net in the early twentieth century. Many southern cities did not offer municipal relief. Instead, denominations and municipalities provided institutional care: poorhouses, hospitals, settlement houses, orphanages, and so forth—all of them segregated, with far more resources for whites than for blacks. Local churches sometimes helped people with food, clothing, and fuel.

At its best, religious aid was limited, and churches scrambled for donations to keep benevolent institutions afloat. Then the bottom fell out. The stock market and agricultural markets crashed, unemployment soared, banks failed, and a drought withered a year’s crops. National income dropped by 50 percent. People were starving, and sick, and broken.

Churches weren’t doing well either. Until 1933, church giving held steady as a proportion of national income, but that still meant a 50 percent loss as demands on church resources peaked. Churches cut benevolent spending first, so now there were more people in need than ever before, and they had nowhere to turn.

Churches that could no longer offer help began to ask for it. Religious leaders spoke less about the inadequacies of poor people and more about the inadequacies of a system that kept people poor. Alongside many other Americans, clergy began to demand that the federal government intervene to aid the suffering.

I wonder if you could say a bit more about that tension between personal responsibility and systemic injustice. If conservative clergy were open to recognizing the systemic nature of injustice under capitalism during the Depression, they did not remain so for long. Why not?

Well, religious leaders talked a lot about personal responsibility, and even Southern liberals distanced themselves from the Social Gospel, or the idea that churches should address problems at the social as well as the individual level. But some also understood that sometimes people faced problems that weren’t their own doing. It was hard to blame a starving child in the street for her misery. So the largest black and white Protestant denominations built institutions like those I’ve named above to protect people they thought vulnerable. Catholics and Jews did still more, and often also proved readier to talk about the hazards of unfettered capitalism.

Many black religious leaders recognized the limits of Jim Crow capitalism, and they further understood that religious charities were often ameliorative rather than corrective. A prominent member of the National Baptist Convention warned in 1931, “The ruthless money-makers are financing our charitable agencies which are caring for the victims of the pitiless economic struggle. . . charity does not make for economic justice.”

Meanwhile, whites moved from arguing that “the first taste of charity is as dangerous as the first shot of ‘dope’,” as the head of a Methodist aid agency put it in 1927, to a concern with systemic problems. The head of the chronically underfunded Memphis Community Fund said in 1931,

I am heartily in favor of bigger and better smokestacks, of more beautiful and taller skyscrapers, of ribbons of concrete threading our country. . . But the man or city which becomes intoxicated for the possession of these while hunger dwells unrequited, while the lives of little children are blighted for want of a chance, is the man or city in which life becomes a hollow mockery and which ultimately loses the material things he has grasped, as he has sluffed off the spiritual.

It was not a complete shift—most Southern religious leaders wanted to salvage capitalism rather than abandon it, but they supported the regulation of business and banking, protections for workers, and the gradual extension of a limited social safety net. They voted for Franklin Roosevelt because he was a Democrat, but also because he promised those things, albeit in vague terms.

Except for the most conservative among them, white clergy actually remained pretty willing to talk generally about systemic injustices throughout the 1930s. But most refused to critique the South’s central systemic injustice: Jim Crow segregation.

Yes. Though Southern conservatives did come to embrace certain of Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, they insisted on local administration that protected and reinforced Jim Crow. How are we to evaluate the virtues and vices of the Southern churches with regard to race?

Southerners adored Roosevelt. He won 96 percent of the vote in Mississippi in 1932! And white Southerners didn’t just embrace the New Deal—they helped create it. Ira Katznelson calls this the New Deal’s “Southern cage”: Roosevelt relied on the support of powerful Southern congressmen who crafted economically progressive but racially restrictive legislation. They demanded local administration of federal programs, and also imposed restrictions that directly affected black Southerners—like excluding agricultural and domestic workers from Social Security.

“Black clergy hoped that federal programs would push beyond the regional constraints of Jim Crow, but feared that local administrators would find ways to deny assistance to African Americans. They were right on both counts.”

In 1935, Roosevelt wrote letters to over 100,000 American clergy and asked for their thoughts about the New Deal, especially the just-enacted Social Security Act and the new Works Progress Administration. A staffer tallied the first 12,096 responses and found that eighty-four percent approved, albeit with some critiques (mostly complaints that Roosevelt ended Prohibition). Across lines of class, race, and denomination, clergy enthused about Social Security in particular. One black minister called it a “divine revelation.”

Black and white clergy embraced the New Deal for different reasons. Black clergy hoped that federal programs would push beyond the regional constraints of Jim Crow, but feared that local administrators would find ways to deny assistance to African Americans. They were right on both counts.

As white Protestants began to divide over the New Deal, leaders of less powerful churches—Pentecostals, independents, black Protestants—built new relationships with the federal government. For instance, Arenia Mallory, an important leader in the Church of God in Christ, pulled her denomination into the New Deal coalition as she formed friendships with Mary McLeod Bethune and other black activists. Mallory visited the White House, and Eleanor Roosevelt supported her work—Anthea Butler has written a lot about these connections. So even as it bowed to white supremacy, the New Deal opened opportunities to black church leaders.

White Southern clergy took note. Many—including Christian socialists and progressives—pushed the New Deal to do more. Methodist Will Alexander headed the Farm Security Administration and tried to ensure black Southerners could access its programs. Others complained that the New Deal threatened white supremacy. They saw their own moral authority in danger, both from the federal government and from churches unlike their own. So some whites broke with the New Deal coalition, but it would be easy to overstate their number. Even those who worried about the New Deal’s racial implications were overwhelmingly supportive of Roosevelt’s policies well into the 1940s.

In recent years we have been muddling through a “Great Recession” in which many of the problems and the arguments of the 1930s have been resurfacing. What can this history teach us about our present political-economic situation?

The Great Depression revealed the inability of voluntary agencies to care for people in a crisis. It showed that churches could provide a place of refuge for the suffering, but they could not alone alleviate that suffering. The New Deal provided the foundation for a welfare state that five decades of Republican and Democratic presidents worked to expand—from Republican Dwight Eisenhower’s work to expand Social Security and raise the minimum wage to Democrat Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society, which brought Medicare, Medicaid, Head Start, and more. These programs were broadly popular, and—for better or worse—encouraged increasing collaboration between the state and religious agencies that helped deliver its programs.

At the same time, a coalition of business and religious conservatives worked to rewrite the history of the Great Depression, to minimize its sorrows and to characterize the New Deal as unnecessary government intrusion. This brings us back to the myth of the redemptive Depression: the idea that the Great Depression taught people self-sufficiency and, when that failed, brought communities together to help each other, and that was enough. The problem with the New Deal was not that it did too little—a more common complaint in the 1930s—but that it did too much.

That narrative shaped the response to the Great Recession. Churches once again called, mostly in vain, for cleansing and revival, but fewer rallied behind any comprehensive effort to address growing economic or social inequities. States like North Carolina and Mississippi—my two home states—have enacted punitive policies that target the poor and minorities as inequality grows ever deeper. Rather than trying new solutions to economic crisis, we continue to roll back old ones. The New Deal was a failure, the logic goes, so let’s toss it all out.

These conservative resurgencies, carefully crafted and long in process, have not gone unopposed. Some of the most powerful advocates for justice during the Great Depression were people who acted from deep moral or religious concern for others but did so outside churches that deemed them too radical, too dangerous. North Carolina’s Moral Mondays movement has likewise made an urgent moral argument for protecting civil rights, a social safety net, a strong public educational and health system. It is a movement steeped in history, and one that demonstrates the best of the lessons we can take from the Great Depression, and from both the New Deal’s successes and its failures.