The title of Ingrid Ricks’s memoir Hippie Boy: A Girl’s Story comes from the nickname Ricks’s father, Jerry, gives her as a young girl with long, tangled hair. It’s the story of a family in Logan, Utah whose profound dysfunction is rooted in part in religion and in part in the economic and social upheavals of the mid-twentieth century. Born illegitimate in Austria at the beginning of World War II, Ricks’s mother relies on religion to give her life stability and converts to Mormonism when she is 16. A few years later, she meets Jerry Ricks, a handsome LDS missionary who sends her a plane ticket to Utah after he leaves Austria.

Jerry’s stint as a missionary exacerbates his hatred of rules; he’s unhappy to find himself saddled with a wife who insists everyone pray six or seven times a day and get out of bed early each morning for an hour of scripture reading. His wife, for her part, is beyond disappointed to find herself married to a man who cheats on her, uses his job as a traveling salesman to escape his obligations to his children, and rarely sends money home. During Jerry’s rare visits home, the parents’ fights are so destructive that Ricks and her sisters “often locked ourselves in the bathroom for protection when they started in on each other.”

Things improve when Ricks’s mother gets a job as a nurse and divorces Jerry. Too quickly, however, she reaches a point where she “didn’t want to make the decisions any more” and becomes desperate to marry a Mormon patriarch who will make decisions for her. And so, after dating him only a month, she agrees to marry Earl, a parasitic, abusive opportunist whom her children justifiably hate.

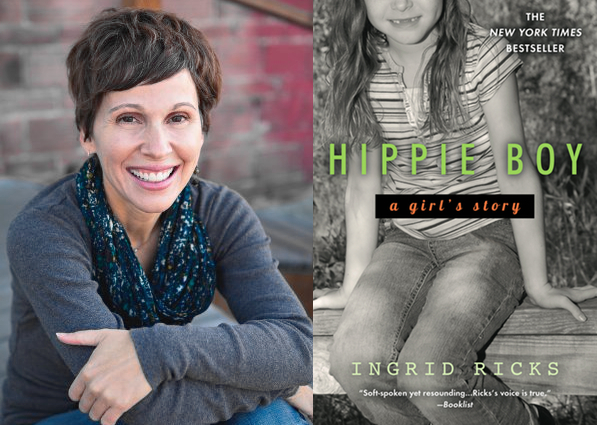

Unable to find a press interested in publishing a Mormon memoir, Ricks self-published Hippie Boy in 2011. Shortly thereafter, Seattle-area teacher Margie Bowker gave the book to her at-risk high school students. They had no problem relating to Ricks’s protagonist, a young girl trapped rather than supported by the safety net religion is supposed to supply, trying desperately to acquire some security despite parents who repeatedly put her in harm’s way. Ricks’s memoir inspired students to begin writing themselves; some of their short memoirs are compiled in a collection called We Are Absolutely Not Okay. Bowker and Ricks also produced a study guide for other teachers interested in using Hippie Boy and their approach to student writing.

Thanks to its popularity with teachers and students and Ricks’s own aggressive marketing, Hippie Boy ended up on the New York Times Best Seller list for e-book nonfiction in 2012 and was subsequently acquired by Penguin, which released the book under its Berkley imprint earlier this year.

I spoke to Ricks recently about the way religion functions in her memoir and how readers respond to her depiction of it.

Hippie Boy has been used in high school curricula for troubled youth. How do they respond to the religious aspects of the book?

Some have had very similar extremely religious experiences, but from Born Again backgrounds. A couple of them have similar experiences from a Mormon background. A lot of the kids relate to having an Earl character in their lives; they’ve had a stepdad who abuses power. Or they relate to having a mother who is powerless to it all and can’t protect them. Or they relate to the poverty. When it comes to religion, some of them say right off the bat, “Yeah, that’s my story.” Others say, “That’s my story—just replace it with this addiction.”

So they see religion as an addiction?

They see religious extremism as an addiction. I also see it as an addiction—at least my mother’s approach to religion. The church always came before her kids and her family. And because of that, there was nothing empowering to me about the religion.

Your mother realizes on the honeymoon that she’s made a huge mistake by marrying your stepfather Earl, but says she can’t do anything about it because she “couldn’t just tell the bishop that I wanted to get another temple divorce.” What sorts of beliefs and fears compelled her to try to make the best of what she knew was a terrible situation? How did she perceive what was supposed to be a loving, empowering religion as one that did not allow her to admit or correct mistakes?

Everybody—including my dad’s mom, who my mother was close to at the time—told her, “Don’t do this. Don’t marry him.” And Mom said, “No, I’m marrying him.” I think as much as anything she was ashamed and didn’t want to admit that she’d made a mistake—particularly since she takes those temple vows so seriously and had committed to Earl for time and all eternity. So the idea that she could go back and say, “I screwed up”—for her, it was easier, at least initially, to just go with it than to admit that she was so wrong and that everyone who had been warning her against him had been right.

The church advocates fairly rigid roles, but people in your family stepped out of their roles in all sorts of ways. Your mother was the breadwinner, and your older sister, Connie, was the protector. This was done so that Earl could maintain the most important role of patriarch and leader, even though he did not fulfill any of its concomitant requirements: he didn’t provide for the family financially or protect anyone from danger. Why was his role as head of the house so important to your mother?

When she says she wanted someone to lead her, I think that says it all. She let me read some of the journals she kept at that time and she did complain about how authoritarian he was. And you also have to look at it in contrast to the dynamics with my dad. My dad hates rules of any kind. His personality isn’t to be domineering—he’d just leave. So it’s like, be careful what you wish for, right?

And then this guy comes in. And she wanted that priesthood holder, the guy who would sit next to her at church, she wanted that so desperately. She quickly found herself powerless because he used his position as a weapon. And when that was so much her belief system—that as a priesthood holder he held that power over her—I think she felt she had no choice but to be submissive.

I have to remind myself that your mother was abused from the day she was born in Austria in 1940, on top of which, she grew up in a war zone.

She just had such a hard, hard childhood. Religion even then was the only place where she found solace. She was Catholic as a child, but converted to Mormonism at age 16, after missionaries from the US showed up at her door. The Church became her family. Then she met my dad, who was serving a mission in Austria, and he helped her come to the U.S. It was supposed to be a dream come true for her—to marry a returned missionary from Utah. But my dad wasn’t the devout rule-following, church-going husband she had counted on. They were like oil and water and my dad was so unhappy that he quickly began leaving for months at a time. So here she is, alone in this strange foreign country and with this husband who hurt her in so many ways.

For many years I punished her for her decision to marry Earl and turn her parental power over to him because it hurt so much. But when I look at it through an adult lens, I understand that she felt so down and so powerless that she couldn’t stand up for us or protect us—because she couldn’t do it for herself.

Tell me about responses you’ve gotten from people who have read Hippie Boy.

The truth about your personal story is, until you start telling it, you think you’re alone, and then you realize, this is commonplace. My situation isn’t isolated to Mormonism. But to suggest that it doesn’t exist in Mormonism is just bullshit. Abuse of power happens in every religion. And when you give someone absolute power, absolute power corrupts. That more than anything is what frustrated me, because there’s still this sense of denial.

On Amazon at first I had a string of one-star reviews from people saying, “This doesn’t happen in Mormonism. If you want to know the truth, go to Mormon.org.” Or someone would say, “I can tell just from reading the description that this woman knows nothing about Mormonism. She ought to study what she’s writing about.” At first I was really hurt, but then you realize, well, it is what it is. But the idea that because it’s not someone else’s experience, they try to deny that it could ever happen, well, that allows it to keep happening.

Tell me more about the abuse and what it did to your relationships with your siblings.

I write about incidences between Earl and my sister Connie, or Earl and me in the book. I also write about once incident where I heard him hitting my little brother. But even more than the physical abuse was the psychological. And for me, part of the problem was that my mom enabled it. She let me read her journals and it got to a point where every other line was, “Poor Ingrid, she has Satan inside of her.” And that hurts. She really thought I was possessed because I wouldn’t conform, wouldn’t adhere to Earl’s authoritarian rule, wouldn’t call him “Father”—the name he demanded that I call him to show my respect.

You provide an afterword, informing readers that your father eventually made his million dollars and that your mother achieved a happy marriage with a Mormon man who was the husband she’d been looking for. It’s very satisfying to know that yours was not the only happy ending to emerge from the painful stories in the book. But can you tell us a little more about what your relationship is like with each parent?

I love both of my parents and have a great relationship with each of them. My relationship with my dad has always been an easy one because in some ways, we are very similar. We both hate rules, we are both dreamers and we both believe in “live and let live.” Our politics and many viewpoints are completely opposite, but it doesn’t matter because we respect each other and feel there is plenty of room for differing belief systems.

It’s been more difficult between my mom and me because she is still extremely devout. It’s hard for her not to continue to push her religious viewpoints on me because she believes my eternal salvation depends on it. But she’s really trying. Ironically, it took her going on a Mormon mission to India with her third husband for us to begin to develop a friendship and appreciate what we have in common.

Her mission was a public health mission and she wasn’t allowed to proselytize or even say anything about religion in her emails home. As a result, her emails were filled with stories about the people and life in India. I’ve traveled to Africa to write stories on behalf of a relief organization and we discovered that we are both adventurous, are both drawn to third world countries, and both deeply care about the struggles faced by people living in third-world conditions. Since then, we both do our best to focus on all of the wonderful things we have in common vs. those that polarize us.