Reading the headlines this election cycle, two broad generalizations about Trump’s candidacy appear: women hate him, while evangelicals continue to support him. If these generalizations are true (even though there are notable exceptions), what can we make of the voting group that embodies both extremes: evangelical women?

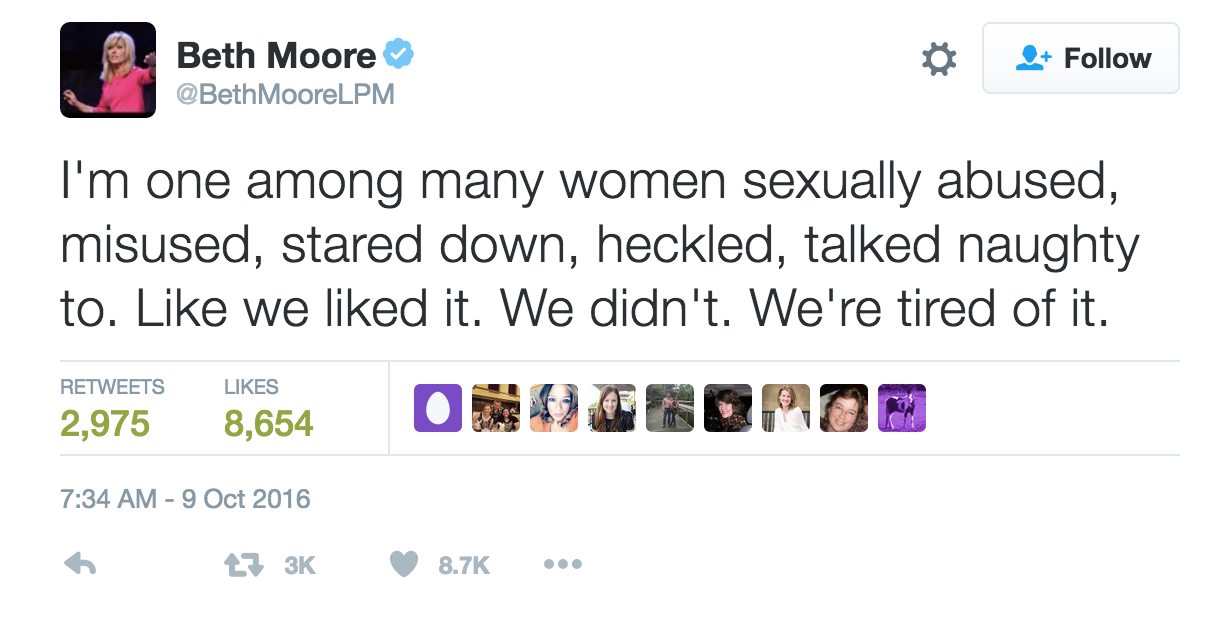

The weekend after Donald Trump’s leaked 2005 audio recording where he brags about sexual assault, evangelical superstar Beth Moore posted a tweet that can only be read as an admonishment of Trump’s defense of those tapes.

Moore writes, “I’m one among many women sexually abused, misused, stared down, heckled, talked naughty to. Like we liked it. We didn’t. We’re tired of it.”

As a nonbeliever (and feminist and queer and liberal sociologist), I have very little in common with Moore, yet I have a strange affinity for her. I first learned about her in 2009 when I was a graduate student with a budding interest in gender and evangelicalism. As part of a research project, I observed her women’s bible studies series, titled “It’s Tough Being a Woman.”

It was during those bible study groups that I first confronted evangelical women’s peculiar relationship to feminism and those issues touted as “women’s.”

Moore herself is theologically conservative, believes in a wife’s submission to her husband, and repeatedly emphasized in the study materials that God created men and women differently. Yet, “It’s Tough Being a Woman” also suggests that women are strong rather than weak, brave rather than fearful. I was puzzled and surprised when the women surrounding me—a group of “submissive” Christian women—clapped and cheered at Moore’s declaration at the end of the first lesson, “We’re going to be some dangerous women for God!”

As a voting block, evangelical women do not appear to vote significantly differently from their male counterparts. This is not the same in the public at large, where pollsters have observed a “gender gap” in voting trends since the 1980 Presidential election. In 2012, this gender gap was at its largest, with 54 percent of men voting for Mitt Romney and 56 percent of women voting for Barack Obama, and it seems likely that this gap will be even larger in this year’s election. Women, as a group with clear electoral patterns, tend to support Democrats over Republicans. Religiosity is also a strong indicator of voting patterns, with weekly churchgoers more likely to vote Republican.

Yet within the evangelical tradition, as political scientist Melissa Deckman observes about the 2008 election, men and women did not have significantly different voting patterns. The gender gap, Deckman finds, is present for secular voters, but not evangelical ones. Though this year’s election seems to defy election expectations in many ways, it is similar to 2008 in that the Republican nominee is not an obviously evangelical candidate (in the way that Reagan or G.W. Bush were). It is likely that evangelical women will draw on their conservative theology to support the conservative candidate.

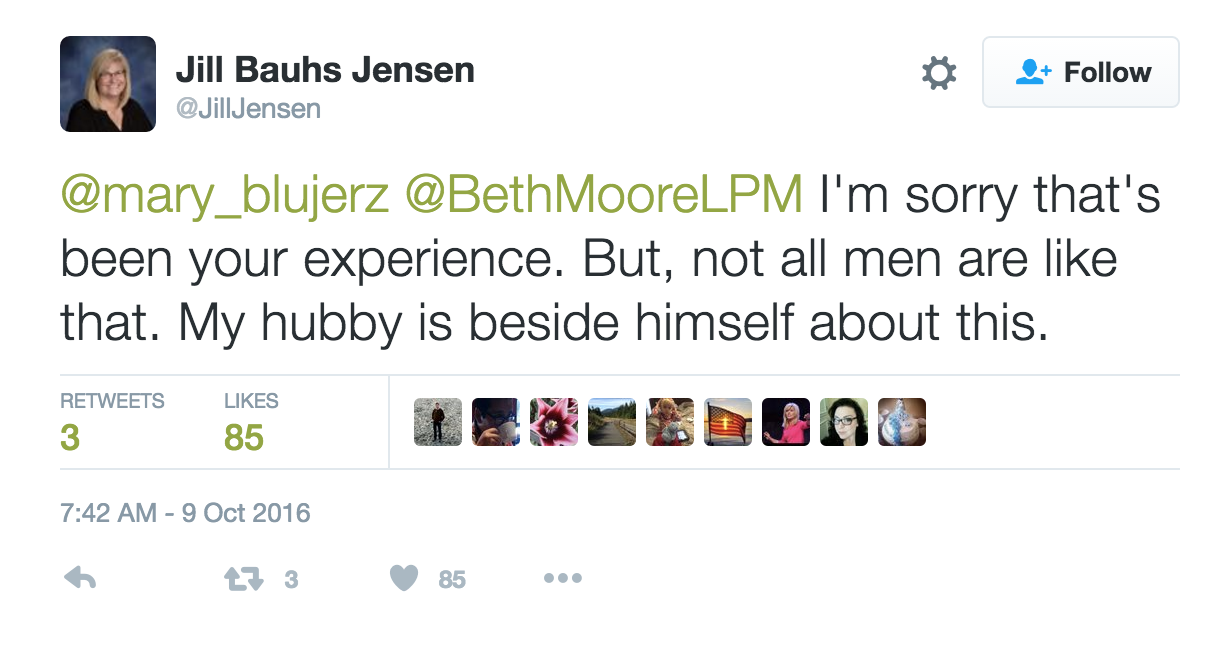

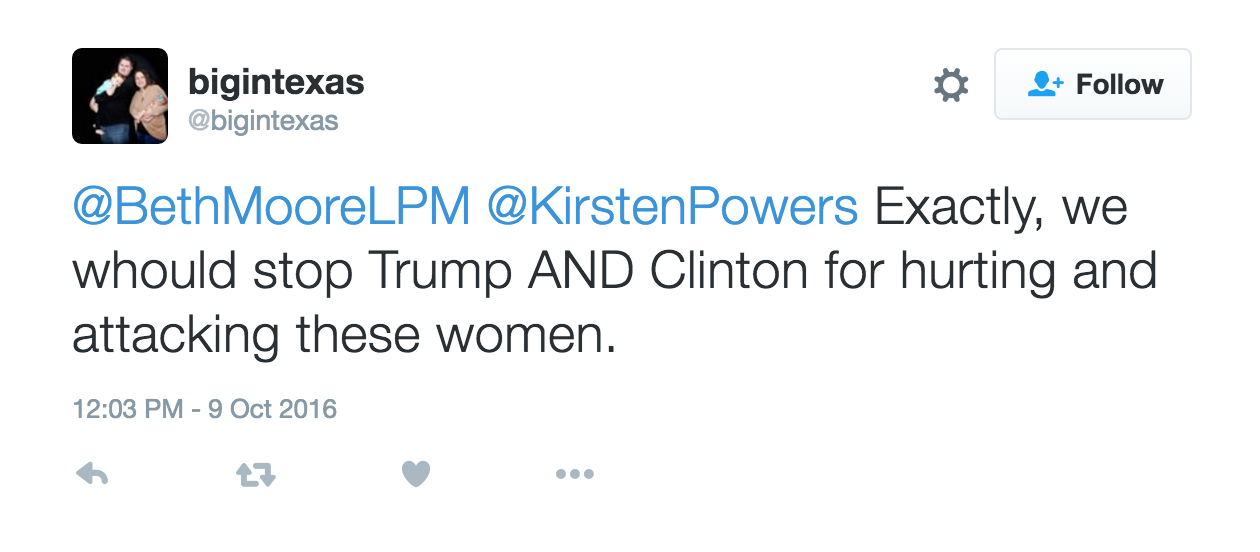

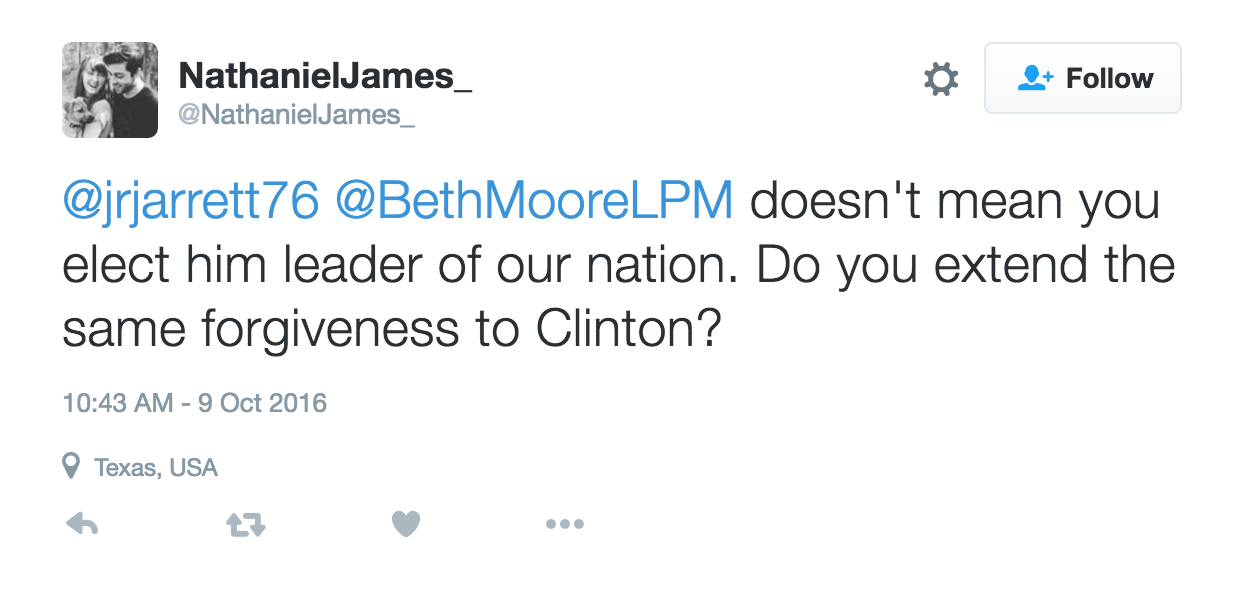

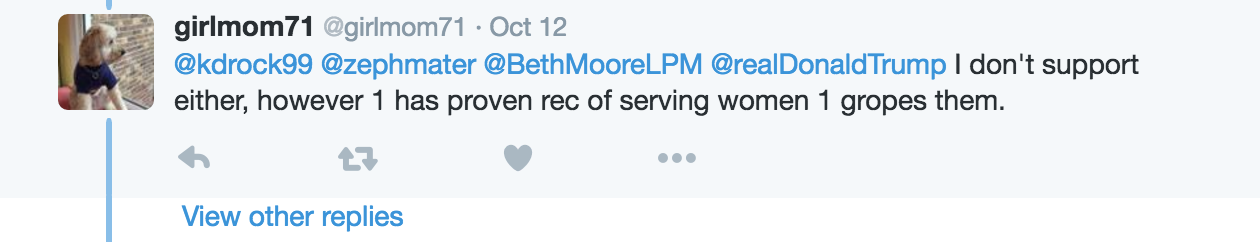

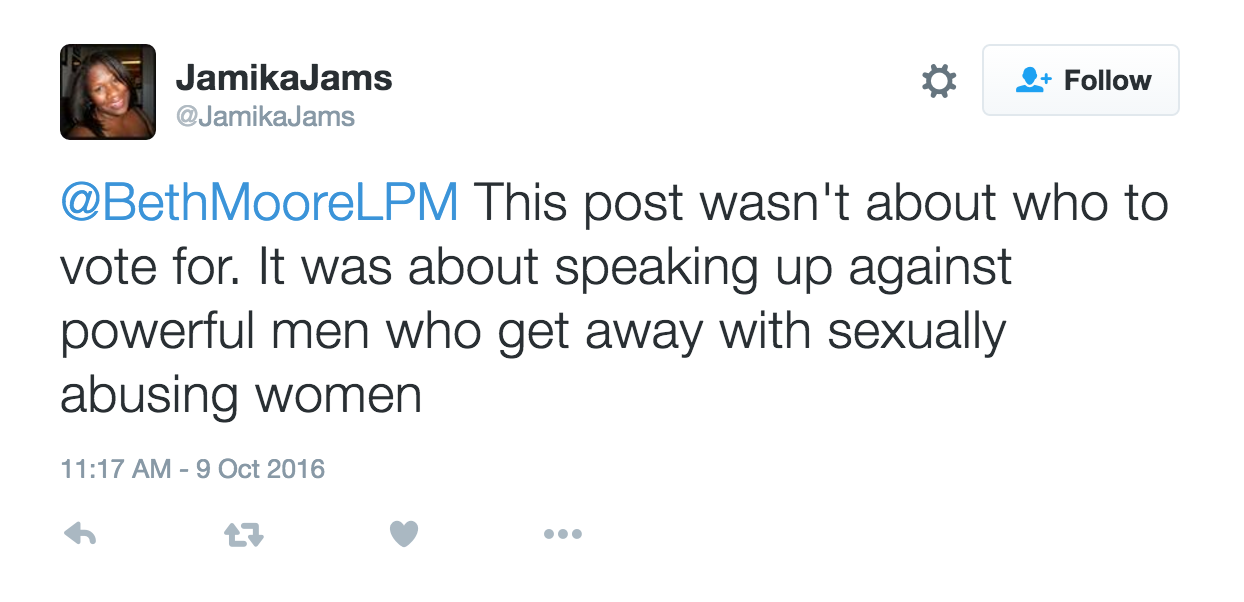

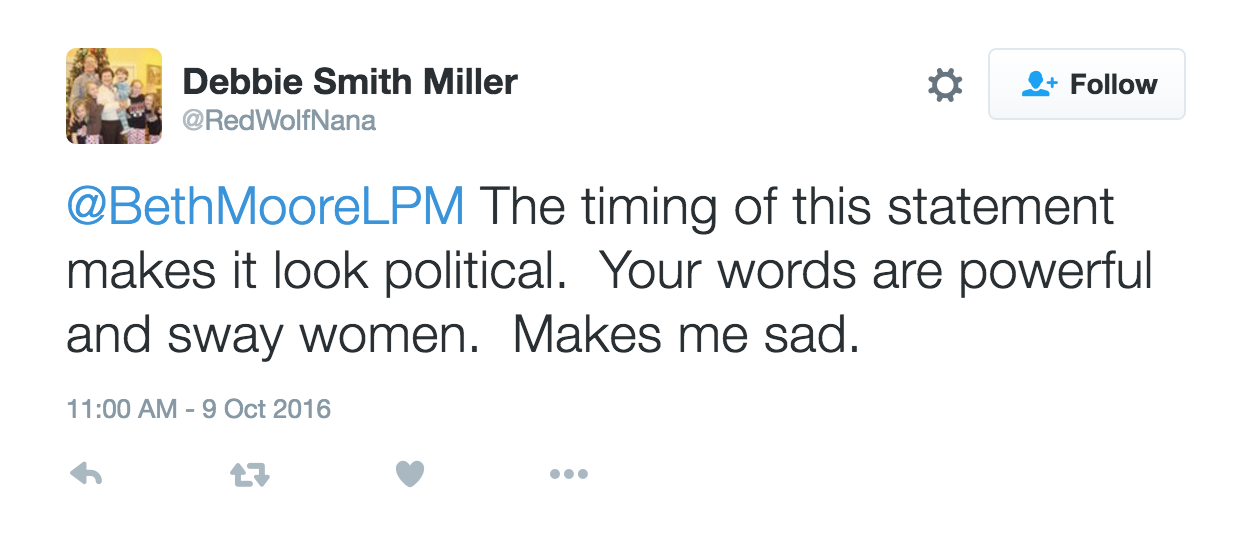

Yet, evangelical women are not a uniform group. Let’s return to Moore’s tweet and the thread that followed. Reading the many, many replies could suggest that all of the following are true:

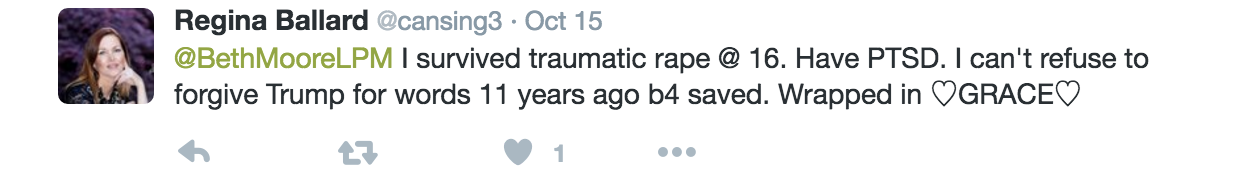

(1) Evangelical women can agree with Moore, while still supporting Trump’s candidacy.

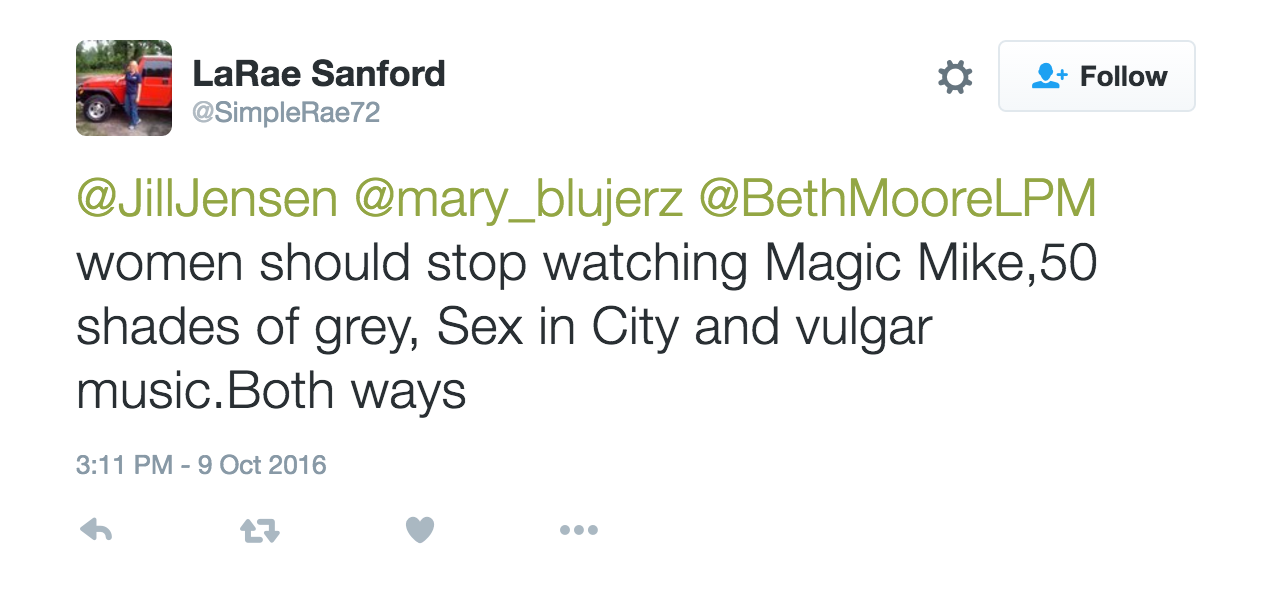

(2) Evangelical women can agree with Moore, while denying the existence of patriarchy, misogyny, or rape culture.

(3) Evangelical women can agree with Moore and reject Trump’s candidacy.

(4) Evangelical women can agree with Moore and choose Clinton as the preferable candidate.

In my research on evangelical women, a lesson I have learned is they can simultaneously live in, observe, and critique what feminists call “the patriarchy,” without ever naming it as such. Instead, they can pivot to a target more universal for evangelicals: secular culture.

But whether it is the secular world, the patriarchy, Satan, or Donald Trump himself, these women’s stories sound remarkably similar to the ones I have read from secular progressives responding to the #trumptapes (examples here, here, and here).

My analysis of the sexual histories of many married evangelical women revealed shared experiences: some were forced without their consent to have sex; many felt pressure to “choose” to have sex even when they didn’t really want to; most struggled with body image and were angry about beauty standards that are impossible to achieve; and all realized in adulthood that sex should feel good for them and they have the right to pursue and achieve their own pleasure.

The common thread in all of these stories, in the words of Moore: “It’s tough being a woman.”

What this teaches us is that the polarizing language we so often use to describe our social world—secular/religious, feminist/traditional, progressive/conservative—may not actually reflect such disparate experiences of living in the world. Yet these divisions remain real, especially when it comes to the ways people vote.

Will evangelical women shift their votes to align more with secular women than religious men? Probably not, since women like Moore can denounce Trump’s deplorable statements, while remaining committed to a conservative faith and rejecting an alignment with a progressive movement. In other words, they can talk about politics, without talking about Politics.

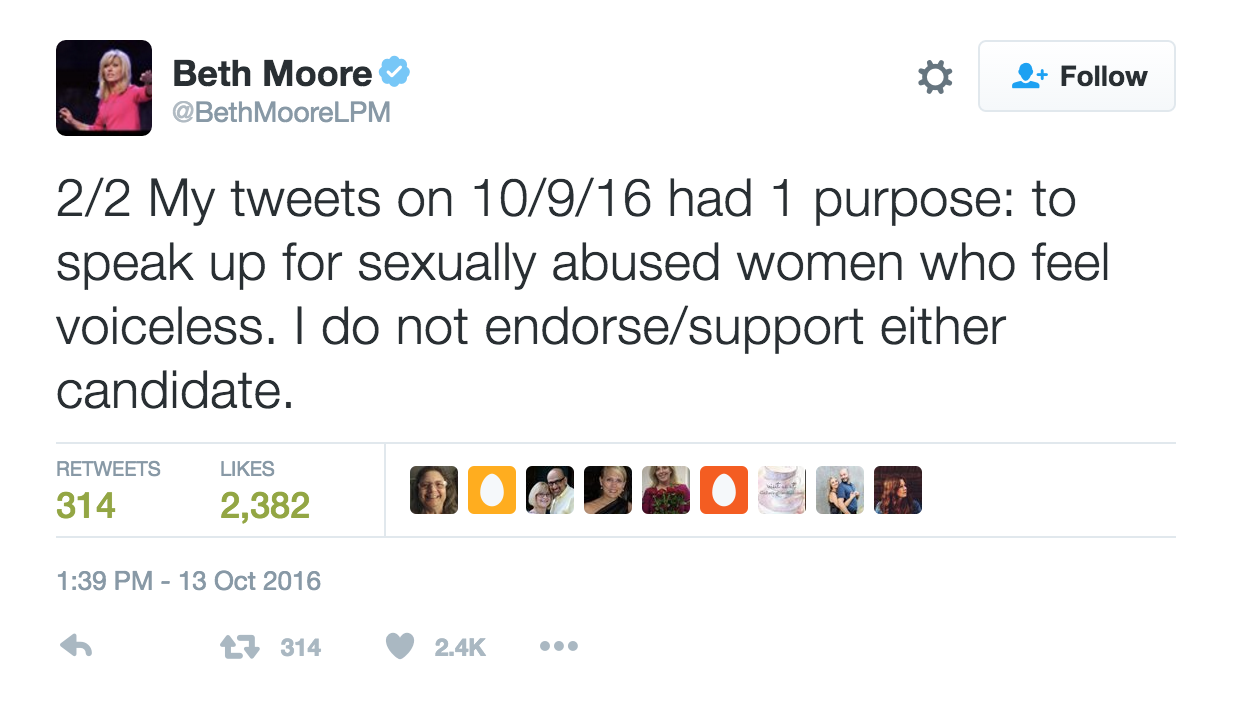

Notably, Moore never referenced Trump directly in her tweet. She later tweeted a clarification: “…I do not endorse/support either candidate.”

She later wrote a blog post that further distanced herself from her perceived critique of Trump, positioning the election as inconsequential compared to the quest of living a faithful Christian life.

That post is currently pinned to the top of Moore’s twitter feed. The tweet that critiqued Trump (and looked like it might be the start of a significant public discussion) is buried far below.