What inspired you to write Race and the Making of the Mormon People?

Let me be a bit confessional. I’m not a Mormon, but Mormon culture has probably formed me more than any other religious culture (even my own). When I was very young, living in Wyoming, my parents were in the midst of an acrimonious divorce. During this time, I spent many hours with Mormon playmates. The contrast between our home life and the loving and caring home life of my Mormon friends endeared me to Mormon culture. It also made me curious about the history that created such a culture—a culture that is welcoming and loving but can be/is often rigid, patriarchal, tribal, and reluctant to change.

Similarly, there is the influence of my one-time stepbrother (of blessed memory), the great Broadway star Jason Raize (Rothenberg) to whom my book is dedicated. When I was a pre-teen, I watched Jason struggle with his own racial and religious identity as he tried to fit into a broader culture that was suspicious and threatened by his unparalleled talents and charisma.

Race and the Making of the Mormon People

Max Perry Mueller

UNC Press

August 2017

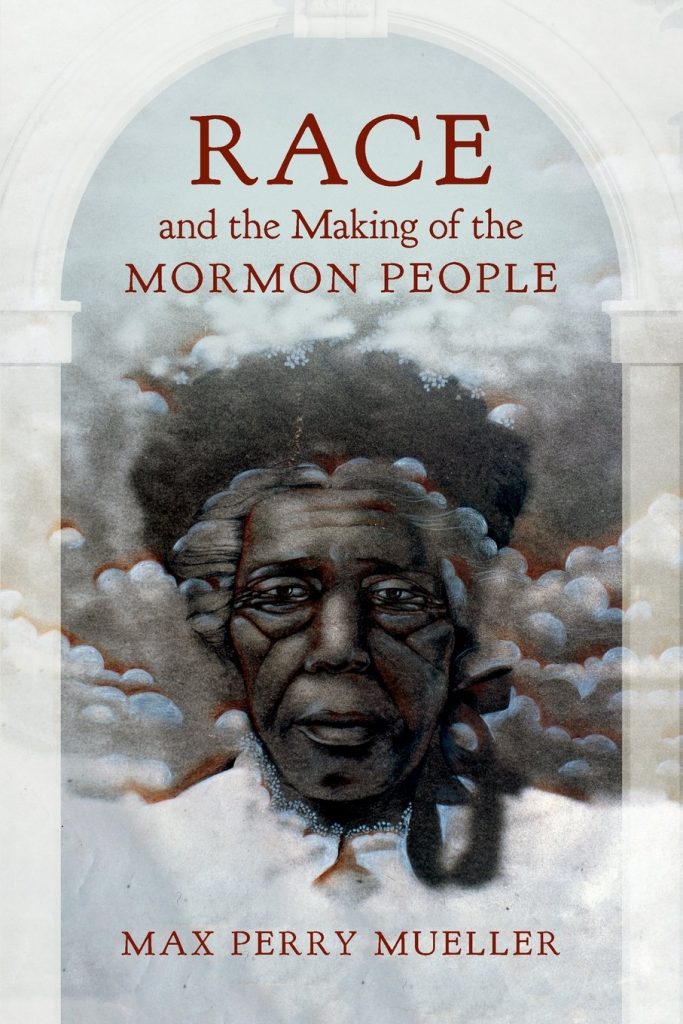

These personal experiences with religious and racial “others”—the Mormons and Jason—primed me to fall in love with the story of Jane Manning James (a painting of James graces the book’s cover). In the early 1840s, as a young, single mother in Connecticut, James converted to Mormonism. She then led most of her family members on a cross-country trek to join with the Mormons in Nauvoo, Illinois. There, she befriended and lived with Joseph Smith, Jr. and his wife Emma Hale Smith. After Smith’s assassination, James was a member of the first wave of pioneers to Utah in 1847 where she remained a faithful member of the church until her death in 1908. Yet by the time she died, the LDS Church had abandoned the (relatively) racially inclusive policies and theologies of its earliest years. Instead, the church practiced and began to formalize the racist theologies and practices for which it would become infamous during the twentieth century.

Initially, I wanted to write a book exploring why James stayed in a church that initially embraced her but, by the time she died, made it clear to her that it no longer wanted her (or at least her racial kind) as a member. However, diving into the rich history of Mormonism and race, the story revealed itself to be much more interesting and complex than a declension narrative from inclusion to exclusion. And “race” in the Mormon context, as it is in the wider American context, is much more complicated and interesting than the “black/white” binary that often dominates our historical and contemporary conversations. Exploring this history helps us understand, I hope, that what we today call the “black” and “white” races emerged out of very specific cultural and legal histories—histories that I argue actually began as religious histories. The book is an exploration of these racial “origin narratives.”

Initially, I wanted to write a book exploring why James stayed in a church that initially embraced her but, by the time she died, made it clear to her that it no longer wanted her (or at least her racial kind) as a member. However, diving into the rich history of Mormonism and race, the story revealed itself to be much more interesting and complex than a declension narrative from inclusion to exclusion. And “race” in the Mormon context, as it is in the wider American context, is much more complicated and interesting than the “black/white” binary that often dominates our historical and contemporary conversations. Exploring this history helps us understand, I hope, that what we today call the “black” and “white” races emerged out of very specific cultural and legal histories—histories that I argue actually began as religious histories. The book is an exploration of these racial “origin narratives.”

In the Mormon context, the beginning of these narratives cannot be understood without a robust and close reading of the Mormon movement’s seminal text: the Book of Mormon. The book presents itself to be an origin story of America’s native peoples and a prophecy about the sacred covenants (religious, legal, and matrimonial) that these Natives would form with America’s white colonizers in history’s latter days. Yet, I argue that the book also has a lot to say about the past and future of America’s three “original” races: “red,” “white,” and “black” (though it’s key to point out that people of African descent aren’t actually present in the book. More on that in a bit).

What’s the most important take-home message for readers?

Americans cannot understand our race past and present without grappling with the power of religion—in particular religious writings—to unify and divide. If race is primarily a construction of culture, then the original construction site was on the page, in particular, as I mentioned before, on the pages of our religious writings. And I’m not just talking about sacred scriptures. I’m talking about all the writings that America’s religious people produce in relationship (intertextually) with their religious scriptures. From public writings like sermons and legal codes, to private writings like journals and letters, these writings all make up what I call the “Mormon archive,” which is a smaller part of the “American archive.” The archive, I argue, is not just a physical and metaphorical space where (race) history is preserved. It is also where (race) history is made.

Exploring the “race of the archive,” as I call it, is a way into studying race as a “metalanguage” to which other (religious, economic, and gendered) divisions have often beeen subsumed. Since race is such an all-consuming category, isolating it in the Mormon context, I hope, allows us to better understand the audacity of Joseph Smith, Jr.’s (self and/or divine-ascribed) mandate to end all schisms within the human family and the failures and limitation of his and his community’s attempt to do so.

More broadly, the take-home message is that, in many ways, the Mormon race story is the American race story. It is story of an ideology of equality—but one that has not only never been realized, but for a period of time, also served to exclude, sequester, enslave, and even kill racialized others.

Is there anything you had to leave out?

Relying on the written archive, as all historians of marginalized communities realize, inevitably leads to the exclusion of certain peoples and the emphasis of others. I tried to foreground the (few) stories of non-white Mormons that we have in the archive, to better understand how they—by fighting against, acquiescing to, and/or accepting—Mormonism’s racialized theologies and practices, greatly influenced the history of race within the Mormon movement. In other words, people like Jane Manning James; Sally Kanosh (Kahpeputz), Brigham Young’s adopted Paiute daughter whom his family bought as a young child from Ute slave traders; and Wakara, the onetime Mormon elder, Indian slave trader and Ute warrior chief, were active historical agents in the race histories that affected their lives.

But the (written) archival sources are limited. In particular, I wish I could have written more about the enslaved Native American women and girls like Sally whom the early Utah Mormon pioneers “bought into freedom” from their Indian captures. We know very little about their fate (though we do know that many died of disease and many ran away. Many also remained indentured to their Mormon masters. Some became plural wives). I wish I could have written more about their stories.

What are some of the biggest misconceptions about your topic?

Let me list a few:

1. That Mormonism is a “white religion.” To be sure, Mormons have historically been predominately white; that is, in the way Americans understand “whiteness.” But Mormon whiteness has always been contested (see W. Paul Reeve’s amazing book on the Mormons’ struggle for whiteness). What’s more, today most Mormons are non-American and likely non-white (the biggest Mormon growth areas are in the African diasporas of Central and South America and Africa). The Mormon people and the LDS Church itself has always grappled seriously with the implications of its racist past and continue to do so (see the church’s statement following the recent white supremacist march and terrorism in Charlottesville as a case in point, in which the church directly confronted the small, but prominent group of white supremacists among its membership. The church told them in unprecedentedly clear terms, your views have no place among us).

2. That the Book of Mormon is simply an anti-African-American text. The Book of Mormon has many troubling passages that speak to the superiority of whiteness. It also has a few (infamous) passages that describe blackness as savage, evil, and cursed. But people of African descent aren’t directly included in the Book of Mormon’s past and prophesied future (which can be, of course, a troubling point to make in itself). Still “race” in the Book of Mormon is not about static phenotype (“white”-skinned people as good and godly; “black”-skinned people as evil and heathenish). Instead race is about dynamic narratology. As I write in the book, race “is less about skin and more about stories—stories about how racial differences came to be in the past and how such racial differences can be overcome in the future” (34).

3. Relatedly, that the Book of Mormon isn’t worth studying. Race and the Making of the Mormon People contains the most sustained analysis of Mormonism’s foundational text of a history of race and religion published to date. Yet my book comes out during something of a “Book of Mormon” moment. Literary scholars are beginning to study it and teach it as a peculiar and deeply complicated text. This is new. It’s a break from the more than century-long tradition of intentional Book of Mormon illiteracy among serious readers (inaugurated by Mark Twain’s famous quip that the book is “chloroform in print,” which was sustained by the likes of Harold Bloom, who said the book does not hold up to a close reading). I hope that scholars and students are now demonstrating that the book does indeed hold up to rigorous analysis. Whatever one believes about its origins, it’s a book of great importance to American and global history. Its global presence, perhaps, is reason enough to study it. It’s been translated into more than a hundred languages. And only after the Bible and the Quran, it’s the third most reproduced religious text in the world.

Did you have a specific audience in mind when writing?

My first audiences are the descendants—spiritual and biological—of the historical figures about whom I write. First among those are the descendants of Jane Manning James and the other black Mormon pioneers (I’m so blessed to have had the support of James’s great-great-grandson, Louis Duffy, as a research partner and confidante during much of the writing of the book). And I’ve befriended many of the contemporary black Mormon pioneers and their allies within and outside the LDS Church who turn to James as a spiritual matriarch. My hoped-for audience also includes Native American Mormons as well as the descendants of Native Americans whom the Mormons displaced, enslaved, and killed to make way for their Zion in the Great Basin. I hope all Mormons who read the book see their history fairly depicted, even (or especially) if they find this history unsettling.

Second, my intended audiences are other scholars of race and religion in American history. Here’s hoping that this book does meet its goals of illuminating something new about how we understand the origins of “race.” And here’s hoping that, armed with this knowledge, we can do something to dislodge “race’s” seemingly intractable grip on the American experience. I also hope the book makes a theoretical contribution to scholars interested in the colonial power of the archive as a tool—wielded in concert with arms of war, alcohol, and disease, and “civilized” notions of dress, farming, and religion—of empire building.

Are you hoping to just inform readers? Entertain them? Piss them off?

I have just spent a decade researching and writing about white supremacy, specifically in the Mormon context. But like a lot of us (by “us,” I mean white folk; non-white folk have always been awake to this truth), Trump’s election woke me up to white supremacy’s enduring hold on our society. I hope that—be they Mormon or not—in the act of getting informed about the relationship between race and Mormonism, readers do get “pissed off,” to use your term. Not at the Mormons specifically (many Mormons—especially non-white Latter-day Saints—are among the wokest people on race around). But instead, I hope readers get upset about how corrosive white supremacy is for all of us—us who have benefited from it, too. Getting “woke” to one’s own implication in this system of oppression is the essential first step to dismantling it.

What alternative title would you give the book?

Jane Manning James told a friend near the end of her life, “I am white with the exception of the color of my skin.” This is a stunning and heart-wrenching confession. But one that encapsulates much of the theology that I explore in the book. I thought about titling the book with this powerful quote. But, as a title, it’s a bit unwieldy.

How do you feel about the cover?

The University of North Carolina Press was very supportive of my decision to place Jane Manning James, who is the heart and soul of my book, on the cover. Ever since I saw this painting of James (which belongs to the LDS Church museum), I loved it. However I worried that it was too hagiographic. But my fears subsided when I discovered that the 1905 pioneer photo (which is included in the book’s opening title page and in the prologue) was the inspiration for the painting. The painting—from the deep, beautiful lines in her face to the flowers in her bonnet—is a faithful rendering of James in the photo, which was taken not long after she described herself as “white.” Though it makes us squirm in our seats today, clearly whiteness meant something different to her than it does to most of us today. Grappling with that reality is one of the challenges of the book.

Is there a book out there you wish you had written? Which one? Why?

There are hundreds! Let me name two. First’s there’s Jill Lepore’s The Name of War. It’s the book that is the most direct (I hope not derivative) influence on Race and the Making of the Mormon People, especially in its analysis of the relationship between the written word and the construction of racialized bodies.

And second, Tom Perrotta’s The Leftovers, and not just because of the licensing checks from HBO! Since my own teen again conversion to evangelical Christianity out of fear of the Rapture and since I returned to Christianity during this slow-moving secular apocalypse that is the Trump-era, I’ve been long obsessesed with the End Times. Yet, Perrotta’s book is actually less an examination of apocalypticism and more about theodicy—why do bad things happen to good people and good things happen to bad people? Perrotta’s observation is that the rapture happens everyday in individual lives when people face meaningless tragedy and suffering.

What’s your next book?

Jane Manning James is the main character of Race and the Making of the Mormon People. But Wakara (1808-1855), the Ute warrior chief, Indian slave trader, famous horse thief, and onetime Mormon who eventually led an Indian uprising against his Mormon brethren when they began to threaten his Ute way of life, plays a key supporting role. My next book, Wakara’s World, focuses on him.

During the 1840s, Wakara was one of the richest, most influential, and feared men—white or Native—in what would become the American Southwest. But few have ever heard of him. Wakara was a founding father of the states we now call Utah, California, and New Mexico. He also stole horses by the thousands from the California missions and enslaved hundreds of Paiute Indians, whom he sold at slave auctions in New Mexico and Utah.

Wakara was a great and terrible man. But we know little about him. And what we know comes from the archive of his exploits—often called “Indian depredations”—recorded and stored in the colonial archive. Wakara’s World attempts to get around this problem of the archive by studying Wakara’s material legacy. Each chapter of the biography focuses on one material object—from “Wakara’s Fish,” the sacred foodstuff of the chief’s tribe that was decimated by the arrival of the Mormons’ irrigation ditches in the mid-nineteenth century, to “Wakara’s Skull,” which late nineteenth-century anthropologists from the U.S. Army Medical Museum dug up from the chief’s elaborate burial site in order to compare its cranial volume with other races.