Tonight, Faith in Public Life, one of the major organizations in the religious left, is…well, let their email tell you:

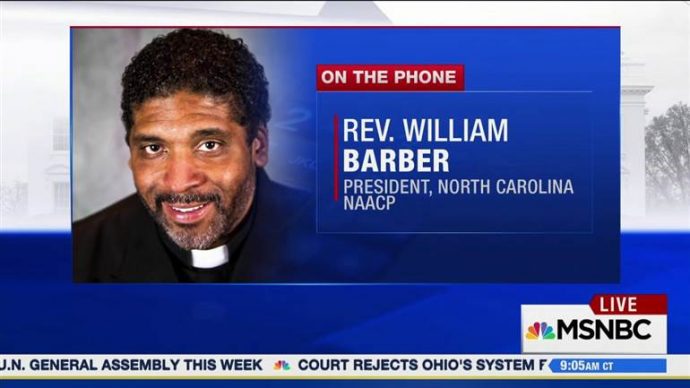

Join us Tuesday night at 8 p.m. EST for a strategy call with Rev. Jennifer Butler and Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II, president and senior lecturer of Repairers of the Breach and leader of the Moral Mondays movement, to outline steps we can take right away to protect our neighbors and our nation from suffering and privation. We need to mobilize now, and this call is the first step.

This healthcare bill is not a Republican versus Democrat issue. The attack on poor and vulnerable children, families and seniors is an issue of morals — right versus wrong. We cannot stand idly by as extremists in Congress and the administration further enrich the wealthiest few at the expense of the sick, the poor and working people.

Together we can awaken our nation’s moral conscience.

It’s significant that Rev. Barber is connecting with the broader religious left movement, something we haven’t seen much of lately. I’ve been wondering when someone would try to roll out the “Moral Mondays” model nationally. This might be it.

But the parts highlighted above are really the ones worth further discussion.

Let me say at the outset that I have no issue with faith communities organizing to fight the AHCA, surely one of the most heartless bills to come out of Congress in recent years—and that’s saying something. If Faith in Public Life and its associated groups have a winning strategy, that’s great! But I suspect they don’t. Admittedly, I’ve been a persistent critic of the religious left for a while now, so take that with the requisite grain of salt. But I don’t think they do, which points to a bigger problem with liberalism in the age of Trump than a mere tactical disagreement.

It’s simply nonsense that the AHCA isn’t a “Republican versus Democrat issue.” True, the bill is widely unpopular and has been attacked from all ends of the spectrum. Even Breitbart hates it. But the legislation itself has been pushed strictly along party lines, as has the entire “Repeal and Replace Obamacare” project. The debate within the Republican party has been largely been about whether supporting it or letting it wither on the vine will create a bigger bloodbath for the GOP in 2018.

That is, what’s to their partisan advantage?

Not to put too fine a point on it, Paul Ryan does not give a shit if he doesn’t get a single Democratic vote for this monstrosity. Ryan is driven by an ideological obsession with cutting taxes and the social welfare programs they support. He can pursue that vision because he has solid backing from the Republican party. (He has had, anyway. Some of them may jump before he drives the bus off a cliff.) Republicans support Ryan’s vision because they, too, are ideologically driven by it. It’s an idea that defines their party.

Why are they so committed to that idea? Partly because that’s just their philosophy. Partly because it won’t affect most of the people who voted for them. And why is that? Because the nation has been gerrymandered and segregated beyond all recognition.

In making that assessment, I am agreeing with my long-time friend and colleague Martin Longman, who has been warning about Dems’ structural geographical weakness, as compared to their demographic strength. The short version of Longman’s argument is that Democratic constituencies are naturally concentrated in urban districts, a segregation (pun fully intended) worsened by Republican gerrymandering. That leaves the GOP with a strong numerical advantage because they can rack up victories in rural districts. That in turn means Republican incumbents are pretty well insulated from accountability, even when they commit egregiously bad legislation.

In order to stop something like the AHCA, Longman suggests, liberals have to make conservatives fear a general election more than a primary. To do that, Democrats will have to contest Republicans in suburban and rural districts. Running up the numbers in the cities just won’t cut it.

So there’s problem one: the AHCA is very much a “Republican versus Democrat issue.” It wouldn’t exist without the extreme partisan divisions that exist today in the US, which are regional as much as numerical. Maybe I’m wrong, and this strategy call has some kind of secret weapon to overcome those divisions. Prayer and appeals to common values won’t do it, and unless they have something that will, the project is going exactly nowhere.

Problem two is this: American self-segregation and gerrymandering are irreducibly a matter of race. It’s not a coincidence that the strongest and most firmly gerrymandered Republican seats are also overwhelmingly white. Add to that courts in North Carolina and Texas finding that those states’ voting laws disproportionately affect African-Americans and other minorities, and the stark racial divides between the two major parties.

I’m about as pessimistic as Martin Longman on Democrats’ ability to address racial differences while avoiding white backlash in the very districts they need to pick up. Like him, I’m convinced that they need more than just better messaging if they’re going to take rural seats. “Awakening the nation’s moral conscience” really isn’t going to work as a frame. Neither is asking WWJD or appealing to shared religious values.

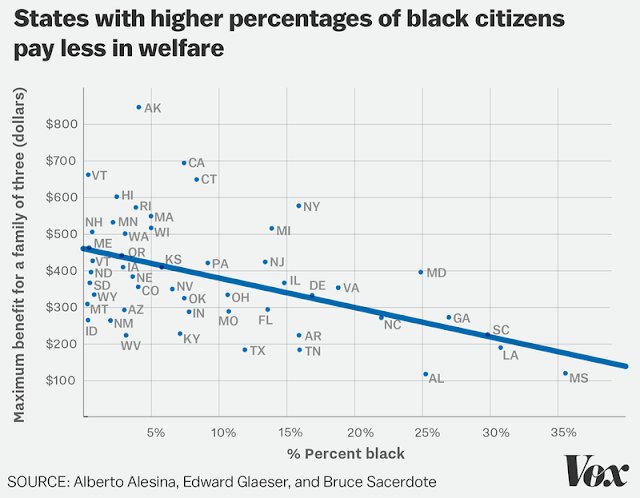

There simply is no trans-partisan set of values that will magically unlock conservative whites from the GOP. Here’s why: “the higher the percentage of black residents in a state, the less its government spends on welfare payments.”

You will notice that with the exception of Maryland, all of those states down in the lower right-hand corner are filled with good Christian evangelicals. Race drives partisanship drives law-making in the U.S.—not faith. As long as that’s the case, people will deflect, deny or find excuses for their racial tribalism, no matter how religious they are.

The herrenvolk have exquisitely woke consciences—but only for the people who look and talk like them. They lump the others into the category of “the undeserving poor” and seek to cut their benefits, a story going back at least to the New Deal. The idea that faith can dislodge this kind of white supremacy and privilege on an electoral level is nothing more than wishful thinking. These people have faith, but it fuels a politics of resentment that isn’t susceptible to change.

Perhaps Democrats will get “lucky” and Republicans will find a way to pass the AHCA despite their best efforts to shoot themselves in the foot. In that case, 17,000 people die in the first year, around 25 million will lose insurance, and the GOP will cease to exist as a national party.

More realistically, liberals are going to have to do some very heavy lifting over the next few years. It’s going to be much harder work than letters and phone calls to Congress, protests, or meetings with like-minded friends.

You can point to the successes of Rev. Barber’s “fusion politics” in North Carolina, but the fact remains that the state GOP passed almost all of their legislative agenda, and has nearly hobbled the incoming Democratic Governor. Ditto, unfortunately, the protest movement that sprang up everywhere after Trump’s inauguration. It haS pushed back on a few things, but regulatory rollback proceeds apace, and it looks like the GOP will get credit for submarining its own legislative agenda.

In any case, this is all really very simple: partisan problems have partisan solutions. To stop the extremist conservative agenda, Democrats have to step through the minefields of race and religion to take more than just a few conservative districts away from the Republican party. That’s the very definition of a partisan project, and it’s the only thing that will work. The only way “to protect our neighbors and our nation from suffering and privation” is the application of raw political power. That takes votes and money above all else.

Again, maybe I’m wrong. Maybe Faith in Public Life intends to pull a strategy for raising money and registering voters out of their hat. I hope they do. But I doubt it, and unless it does, it’s just going to be another in a very long list of progressive attempts that didn’t even lay a glove on the nation’s problems.