In nearly four decades as a journalist, I have observed that religion professionals of all traditions suffer from a constant case of academy-speak. In fact, one of my greatest challenges as a religion writer has been to translate what theologians say so that readers can understand them.

So while I’m delighted with Religion Dispatches’ recent essays encouraging theologians to get down with contemporary media, I fear that using new media won’t be effective without some changes in attitude and approach. Therefore, as a practicing journalist and lay minister in my own Christian denomination, I make so bold as to offer the following guidelines for theologians trying to connect with us common folks in the pews, temples, synagogues and mosques of the world.

1. Get a media mentor.

Many seminaries and universities are still wedded to a high-literate culture that’s fast fading away. This is blasphemy to academics, but the message here is: Leave the books on the shelves and get on the Internet, pronto. Those who don’t know how to get online (for shame!) should get a colleague or student to teach them. In fact, why not get students to help produce a “talking about God” multimedia moment? The result may convince a seminary or university to add contemporary communications as a required subject.

2. Talk to us, but don’t talk down to us.

Wait, this isn’t an anti-intellectual screed. High-level intellectual discussions about religion stimulate many of us, but such dialogues aren’t going to help religion penetrate contemporary culture. Not only must theology be relevant to contemporary culture, it must be understandable by those in the culture. Otherwise, we faithful won’t be moved to apply our beliefs in search of a common good.

3. Check the literacy level.

I once edited a theologian’s commentary that tested out at a post-doctoral reading level. Since most U.S. citizens’ reading comprehension has now dropped to between 6th and 8th grade level, how well would the theologian’s essay have been understood in its original form? Fortunately, there are plenty of online resources that will test a manuscript’s reading level. Try writing for a maximum 10th grade comprehension.

4. Think “story.”

This caveat flies in the face of rational Enlightenment academia, but that’s not the audience being sought. Telling stories – jokes, family tales, urban legends, television, movies, books, Internet – has been the primary way that people have shared information since the dawn of civilization. Only in the past 500 years has our inherent gift of story been downplayed by detached rational argument. Nonetheless, an undercurrent of storytelling survived and thrives today as people are surrounded by narrative in multiple media. Thus a theologian’s message needs a good narrative hook to get people’s attention.

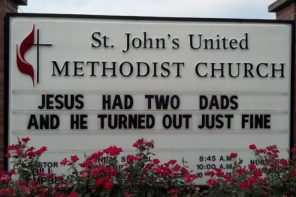

5. Think “image.”

Image and story are inseparable. Jesus’ parables remain effective after 2,000-plus years because they so skillfully combine real-life images with challenging theology. Do thou likewise.

6. Think “music.”

One of the fastest-growing forms of Christian worship today is the “U2charist,” an order of worship developed around the music of the Irish rock band, U2, and its frontman-philanthropist, Bono. This contemporary Eucharist emphasizes compassion and includes an offering for ONE, the global campaign to end poverty. Gimmicky? Yes, although the gimmick was created by an Episcopal clergywoman in Maryland and not by the band. The point is that the form gets people’s attention, combining ancient Christian worship with memorable music and achievable mission. What music, what lyric, could help frame public theologizing in new media?

7. Be a real-live action figure.

We live in a world desperately seeking to cope with what’s facing us. Our times may be no more fraught than any other period in history, but we have something that no other era of civilization has had – the ability to document issues and events instantly as they happen through global media. Therefore, it is no longer sufficient for an expert simply to lay out an argument; one must suggest at least one concrete action to embody the idea. Furthermore, those who counsel us common folk to rise up on behalf of the poor had better be prepared to climb the ramparts with us. Better still, get out in front and lead the way (film at 11, YouTube 24/7/365). See Martin Luther King Jr., William Sloane Coffin and Mohandas K. Gandhi.

8. Emulate John Wesley.

Methodism’s founder, an Oxford don, gained ground in his spiritual movement only after he agreed to “suffer myself to be more vulgar,” that is, to preach in the open air. Wesley didn’t know how to reach the masses when he began his ministry, but he learned quickly. We Methodists often joke that Wesley, a devoted pamphleteer, never had an unpublished thought. If he were alive today, there’d be a “Grace-Upon-Grace.com” web site emitting plenty of tweets, pokes and emails. Follow his example.

9. Lose the old polarities.

Again, ’tis sacrilege to suggest that liberal-conservative poles no longer define theological argument. However, the waning influence of the religious right, demonstrated by the election of a U.S. president who’s trying to reach beyond partisanship, shows that old polarizing arguments are fruitless today. If theology is to help us find a way out of the mess we’re in, it must get beyond the stalemate of liberal vs. conservative thinking.

10. In the words of Star Trek’s Captain Picard, “Engage!”

Put another way, a theologian is toast if s/he doesn’t respond to comments on a blog, or include a Q&A in video, or put her/his email at the end of each article published in any medium. The ivory tower of solo scholarly contemplation has been succeeded by the discourse of the public square, which is now found on the Internet.

Granted, engaging in theological discussion with laypeople may be foreign territory for some scholars. And no, we laypeople probably can’t outline the history of Christianity in 500 words, or recite the Upanishads from memory, or translate the Codex Sinaiticus from Greek. However, theologians who would like to influence public policy and social change will find us laypeople a bountiful resource as well as an audience.

We can tell you what it’s like to sit up all night with an ailing, aged parent and still have to go to work the next day because there’s no compassionate family leave policy. We can tell you what it’s like to take home-cooked food to an AIDS hospice, and dine with dying people who have been beggared because there’s no national health care. We can tell you about building a Habitat for Humanity house for a divorced mother with three children, who had been living in rat-and-roach-infested public housing because there was no decent, low-cost housing available.

In other words, we laypeople often embody the divine about which theologians teach. If we are to move from the moment’s charity to a changed future, isn’t it about time we collaborated through today’s media?