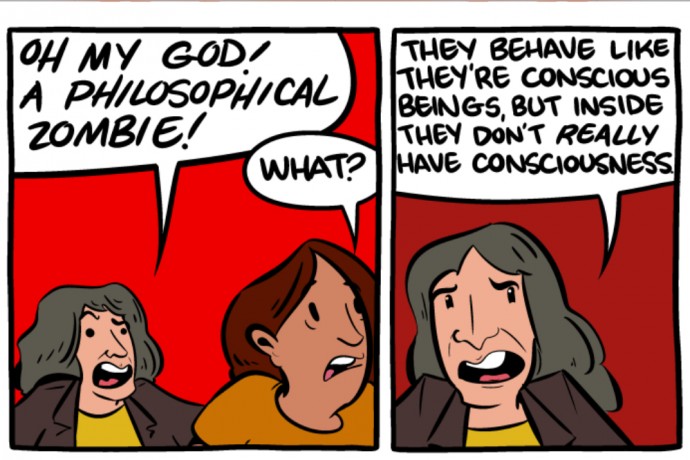

Could we be living in a simulation created by an advanced civilization? Philosopher Nick Bostrom argues that it’s possible, at least in theory, to create a program in which artificially conscious beings inhabit a simulated world. If that’s the case, humans may eventually create a multitude of these simulations—and it’s possible that we are simply someone else’s artificial world.

This is a difficult, technical concept—the kind of stuff that gets kicked around in university seminar rooms, but rarely jumps the walls of academia. Or that’s what I thought, until a scholar friend of mine was talking over dinner about the simulation hypothesis and someone exclaimed, “Oh, yeah, I saw that on a Rick and Morty episode!”

Rick and Morty, a show about a scientist and his grandson’s interdimensional adventures, is more often associated wth crude humor than metaphysics. Intrigued, my friends and I found the episode in which Rick creates a world of conscious beings in order to power a battery. Those beings created another simulated world to power their batteries, and so on and so forth.

It was, indeed, the same theory my academic friend had been describing, except this time it was appearing on Adult Swim, not in Philosophical Quarterly.

***

Some have argued that public philosophy is in decline. Harvard philosopher Michael J. Sandel has suggested that civic leaders in the United States dodge serious moral and religious discussions, and legal scholar Richard J. Posner has lamented the dearth of proficient public intellectuals.

But these doubters clearly need to turn on their televisions. Using the technologies of animation, cartoon creators are engaging in a kind of metaphysical and philosophical playfulness that’s more serious than it might seem at first. These shows can offer crude and silly entertainment. But, increasingly, they’re doing something else: offering a prime place in contemporary culture for theological and philosophical exploration.

Some of these cartoons are intended for adults, and tend to include a lot of cursing and dark humor. This group includes Futurama, Bojack Horseman, and Venture Brothers. The most cerebral of them is probably Rick and Morty. The title characters traverse space and time in episodes that almost always center around an intellectual theme. In one typical episode, Rick creates a being that exists only to serve others and eventually just wants to kill itself. In another, he invents a device that makes the family dog intelligent (it eventually becomes horrified that his species has been enslaved and degraded for so long).

There are also a number of “children’s cartoons” that are really aimed at older children and adults, meant to speak to both groups on different levels. Cartoon Network’s Adventure Time, for instance, is a children’s fantasy show in which a boy and his dog go on quests. The stories are simple enough to appeal to a younger audience, but the writers manage to throw in a good deal of mulling over fifth dimensional objects, alternate timelines, and questions about whether anyone is essentially good or evil. Finally, anime shows, which aren’t expected to fit into the neat categories that most American cartoons are, include dozens of spiritual and philosophical cartoons, including Bakemonogatari, Psycho-Pass, Kino’s Journey, and Japanese anime series Mushishi, which is set in a world where a man named Ginko solves Shinto-esque spirit-related problems

Finally, anime shows, which aren’t expected to fit into the neat categories that most American cartoons are, include dozens of spiritual and philosophical cartoons, including Bakemonogatari, Psycho-Pass, Kino’s Journey, and Japanese anime series Mushishi, which is set in a world where a man named Ginko solves Shinto-esque spirit-related problems

So what makes the medium so ideally suited to metaphysical musing? I can think of at least five reasons:

1. There are no physical limitations.

You can make cartoon characters grow, shrink, turn into things, toss around the Sun like a football—whatever you want. Any thought experiment that can be visualized can be animated.

For instance, in one episode of Adventure Time, a boy creates a fourth dimensional object that turns into a black hole and sucks up the world:

When considering metaphysics, you roll the universe into a ball. You toss around atoms and stars, black holes and the space in your mind behind your eyelids. Scenarios like these are impossible to show in real life and hard to show in live action, but they’re the pencil and ink of cartoons. Thanks to the freedom of animation, Adventure Time writers are able to create a neat reflection on experiencing more than three dimensions.

2. Nobody’s tuning in to watch Matt Damon fight ninjas

Sure, you can have two cars turn into giants and attack each other using Krav Maga before exploding in a fiery blaze that covers the Earth, but nobody watches cartoons for cool fight scenes and explosions. That stuff is just too easy in cartoons, which are plenty bright and flashy when two characters are just sitting and talking to each other. In the cartoon short Manley, for example, a fight scene plays second fiddle to a sort of vision quest:

In one Mushishi episode, a fungus-like spirit kills children and shapes itself into the form of its victims to get protection from mourning mothers. But the show doesn’t focus on an exciting battle between humans and fungi. In fact, the scene where Ginko vanquishes the fungus is quite mundane; Ginko just calmly injects the fungus with a formula. The scene’s most dramatic moment comes in a trippy conversation between Ginko and the fungus. The fungus argues that it deserves to live just as much as humans do. Ginko agrees that neither humans nor fungi are at fault. “However,” he explains, “We’re stronger than you are. That’s why you’re going to die”:

Nor do people watch cartoons for hot actors because, you know, there aren’t any. You usually don’t even know who is voicing a role. People watch cartoons for the ideas: the worldviews, the jokes, the conversations.

3. Cartoons don’t get hung up on words.

“The Tao that can be spoken is not the eternal Tao,” says the Tao Te Ching. The idea that can be named is not the eternal idea. When you take an idea and shape it into letters, you lose something. You pitch it into a world of yesses and nos, of ones and twos.

Perhaps that’s why, when people try to discuss philosophy, they often end up fighting over semantics. Does Cartesian dualism really oppose all conceptions of metaphysical unity, or is that just how Descartes was trying to express an idea about the existence of the supernatural within the limits of language and the ideas he knew? Or are we running into problems in translation? Or disciplinary gatekeeping?

Did you understand that last paragraph? Philosophical writing can be inscrutable for non-experts. And God help you if you’re trying to compare Western philosophy to Eastern philosophy to theological texts to anthropological journals about Siberian Shamanism to neuroscience to quantum physics. It’s a nightmare.

Cartoon writers bypass all these problems by showing you directly what they’re thinking about. In cartoons, you don’t have to box ideas into familiar divides or argue over definitions. You don’t need to know about kami or the Tao Te Ching to see the river of light in Mushishi. You don’t need to have read Kant to smile when Futurama robot Bender realizes that he’s just been imagining his last adventure, and perception is what you make of it. Nor do you have to subscribe to philosophy journals to understand Rick’s world within a world within a world, each with progressively fewer cool spaceship ramps. It’s about the ideas, not the jargon.

4. Weird is normal.

People accept weirder things when they come in cartoon form.

Most television shows and movies fit neatly into a genre, or at least one consistent storytelling mode. Seinfeld never got in a spaceship; Dr. House never spoke to the camera.

But with cartoons, there’s not so much concern about genre-mixing; it’s okay to blend daily life, sci-fi and fantasy. Jesus, a magical unicorn and a time machine can all show up in a single scene of Family Guy, and it feels totally natural that the rest of the episode is about going to the dentist. American Dad is a family comedy about work, school and relationships—in which one of the characters happens to be an alien. Half of one Rick and Morty episode can be about interdimensional travel, and the other half about a teenager upset with her parents, and that’s okay.

This sort of weirdness means writers don’t need to separate the mundane and the transcendental. It means that, when his sister threatens to run away from home, Morty can point to his own grave in the backyard and explain that he and Rick once bailed on their own reality and came to this one, in which he and Rick were already dead. They buried their bodies and took their places:

“Nobody exists on purpose, nobody belongs anywhere, everybody’s gonna die,” Morty says, so, “come watch TV.”

5. People aren’t offended by stuff that happens in cartoons, so there’s more room for moral ambiguity.

Think about South Park. Or take the Rick and Morty episode in which Rick creates a new, lumpy form of life in his laboratory. Rick pets it, comfortingly, and then puts it under a laser beam that burns it alive. Indie pop plays in the background. Then Rick attempts suicide.

If Rick and Morty were live action, that would have been a horror scene. But in a cartoon, it was relatable and, well, kind of funny.

Normally in television (and real life), there’s a limit on how much you can do so without being labeled a sociopath. Cartoons provide a cheerful face to dark, complicated things—death, violence, destruction, the nature of reality—without requiring emotionally investment. In fact, jokes have fun with death. In South Park, Satan’s the king of the underworld, but he’s also a guy with relationship problems.

Heavy ideas often make people uncomfortable. Just having a different political view from a friend can lead to some awkward conversations, even if you’re just arguing over how you think a new tax will affect the job market — let alone bringing up the possibility of a lonely, mad scientist-like creator god. But in cartoon world, it’s all kosher.

***

Cartoons don’t look like photos, and that matters. A cartoon tree isn’t a tree; it’s the idea of a tree, sort of like a Platonic form. It’s about what the tree means, not what it is.

As cartoonist Scott McCloud puts it in Understanding Comics, “By stripping down an image to its essential meaning, an artist can amplify that meaning in a way that realistic art can’t.” It instantly becomes easier to explain ideas visually. Another way to put it: cartoons are theoretical by nature, so they turn into theory easily.

A rich, new form of philosophy is on the rise in the public sphere, and it’s got a lot of bright colors and anthropomorphic animals. This democratization of philosophy matters. It means that talking about a show you saw last week can easily turn into a philosophical discussion, and one not weighed down by elitism. It means that people who never thought about metaphysics are thinking about it, and from a very young age.

Cartoons provide a vehicle for philosophy that’s more playful and open-ended than the sort in sermons or journals, one that doesn’t attach “-isms” to itself, demand its audience take metaphysical sides, or even take the questions too seriously.

Big questions are tough. Questions about the nature of reality, the existence of a God or gods, death, souls and the essence of morality are hard to even talk about, let alone answer. If you don’t want to get bogged down by the very philosophical heaviness you’re traveling through, it’s good to take along a couple of giant googly eyes and Dr. Seussian twisty shapes to loosen your convictions, and to point the way.

After all, they’re just cartoons. They’re not real.

Right?

Also on The Cubit: Does a Star Wars videogame invite players to the Dark Side?