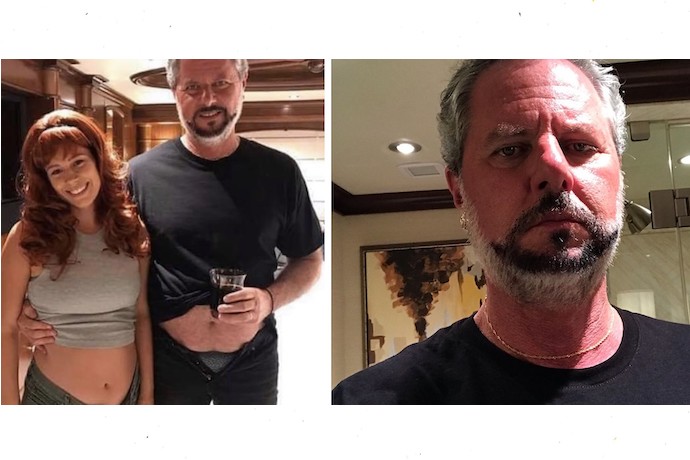

When news broke this past Friday that a controversial Instagram photo would result in Jerry Falwell, Jr. taking an “indefinite leave of absence” as president of Liberty University, it was only the latest in a string of incidents with Falwell at the center of the public spotlight. The offending picture features Falwell holding a dark-colored drink (which he calls “black water”) and his arm around a female friend’s waist. Falwell’s pants are unzipped, with his stomach and underwear intentionally exposed in a way intended to mimic his friend’s similarly-bare pregnant belly.

This photo may strike some as a relatively tame reason for Falwell to be ushered from the stage, at least compared to his other, more controversial statements—including everything from calling the threat of Covid-19 an overblown political hoax to posting overtly racist photos on social media—but there’s an irony here that begs to be considered.

Since President Trump has an even more consistent history of doing such controversial things, and since many white evangelicals (including Falwell) still staunchly support him, it might seem odd that Falwell, of all people, ended up being the one to make evangelicals flinch to this degree. Was the issue really that he was a bad role model—that his clothing and mystery beverage were in violation of Liberty’s student code of conduct (as some students were quick to note)? Or was this just the final straw in an already-collapsing heap of negative attention?

As a scholar of religion and American culture, I would argue that these aren’t the most helpful sorts of questions to ask. Rather, if we want to understand what’s going on here, then we need to think of this photo as a moment exposing a contradiction that coexists somewhat uncomfortably within evangelical political circles about how to handle male indiscretions—particularly those of a sexual kind.

This contradiction involves telling two conflicting stories about manhood. One version of this story views men as natural leaders whose masculinity also makes them virile and sexual. In this telling of the story, male sexuality is understood as a natural, positive, god-given force, the simple outcome of “boys being boys.” It is this power that makes productive societies and productive (read: heterosexual) families.

But all men’s sexuality isn’t equally valued, of course, and so another explanation must be available. This second tale understands the male libido as a type of distraction or weakness, a force that moral discipline cannot harness. For those familiar with evangelical subcultures, these are described as normal desires contorted by sin; descriptions reserved, for instance, for gay men, for those who create unwed mothers and broken families (read: Black men), or for those who use porn.

Both sides of this story are necessary to sustain the political landscape; one can only claim the right to power if one can also claim to know the difference between its good and bad versions. The critical question, then, is which type of story the public wants to believe about Falwell and his legacy.

As I discuss in my recent book, Compromising Positions, on American political sex scandals and the influence of evangelical culture, this two-pronged story has been at the center of the way that many Americans have responded to their leaders’ sexual indiscretions. Even though many evangelicals have built their cultural capital on a platform of straitlaced sexual morality, there’s been extraordinary tolerance among this group for politicians who commit what are traditionally considered immoral sexual acts—so long as they meet certain conditions.

If the politicians in question are white, straight, and come off as “tough guy” protector types (think Roy Moore, Arnold Schwarzenegger, or Donald Trump), a persona more common among conservatives, then such politicians need not apologize for, nor even confess, their sexual wrongdoing, which can be read as an admission of weakness. When they break the sexual rules, this is often seen simply as a side-effect of their powerful masculinity—the same force that compels them to conquer and protect.

On the other hand, there are plenty of politicians who are not understood in this more righteously aggressive, hypermasculine way (think of Democrats John Edwards and Anthony Wiener). Their political fate was sealed, and negatively so, not because their sexual violations were considered particularly heinous, but because neither one built their political personas around threats of an impending national enemy. As a result, there’s no other way to talk about, or justify, or translate their wayward sexuality that can redeem them as strong, national protectors.

With this in mind, what that photo exposed is far more than Falwell’s underwear. Rather, it exposed the fact that playing political hardball involves a tricky calculus regarding which story about masculinity the public will more readily digest. More to the point, that story is only palatable to the extent that it can assure that same public that it can idolize these forms of masculinity while also convincing itself that it still has moral standards.

To be certain, the Falwell photo hardly constitutes a sex scandal, unless one is measuring it by the Jimmy Carter scale (and here I refer to Carter’s non-scandal, or the 1976 Playboy interview when he admitted to lusting after women not his wife and thus committing “adultery in my heart.”) Nevertheless, it’s quite clear that the abandon with which Falwell put his body on display forces the question of which story the conservative public is willing to tell not so much about Falwell, but about themselves.

Even though Falwell has made plenty of brash moves that might connect him more closely with “tough guy” status, he’s not a politician who can be vicariously associated with national pride, but a university administrator at an institution known more for its extremely rigid rules than perhaps anything else. And though his family’s legacy is deeply responsible for the contemporary drumbeat of Christian nationalism that’s been so vital to the popularity of people like Donald Trump, the conservative public doesn’t read Falwell as a vicarious extension of itself in the ways that Trump commands.

Plainly spoken, Jerry Falwell, Jr. is not understood by the broader conservative public as a type of national treasure. He doesn’t personally mean enough to conservative Americans to preserve him as an ideological leader, and thus he will go the way of many others who also couldn’t be easily understood as a symbol of national strength. Although no one knows what his future holds, at the moment it’s far more politically expedient to sacrifice Falwell than to perform the political gymnastics necessary to save him.

Following those many politicians whose sex scandals end their careers, Falwell has already begun to submit to his fate by apologizing repeatedly and promising to be a “good boy” in the future. Politics is a power game, after all, and those who show weakness are often already dead in the water. In this sense, Falwell’s cultural situation reveals much more about the moving target of morality than any one single photo might suggest.