New York City has the reputation of a place with absolutely zero patience for BS. This is a money-city, a global financial center driven by real estate, banking, and the stock market. Yes of course New York is the American center of theater, fine art and publishing; but even with these folks the talk is of money, financing, advances, sales figures. The pandemic will change a lot of things about New York City, but not its obsession with money.

Of course, I can think of a few complicating factors. The outgoing president is the Emperor of BS, and he is, or was, a New Yorker. (Florida can have him.) The second is that finance itself often seems like a kind of magic; Marx writes of capital’s “occult quality of being able to add value to itself.”

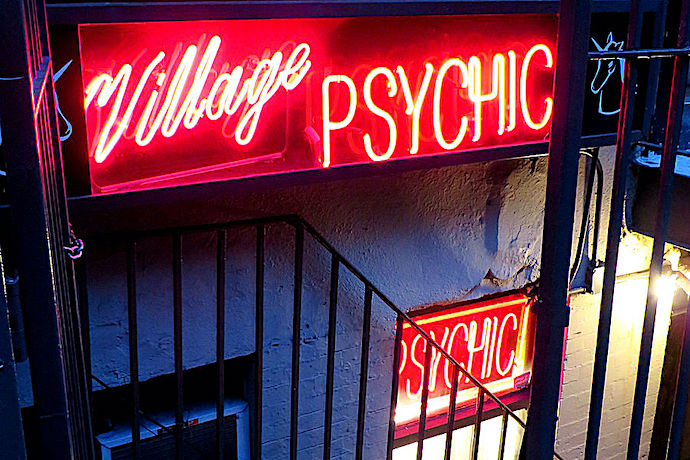

But I’m leading up to something else: magic. Not rabbits and hats, but actual supernatural practices beyond the orthodox religions—mesmerism, spiritualism and the like. Because New York City has long been a magnet for those seeking access to hidden forces, or to reveal them. Whether we believe in it or not, there’s no denying that magic runs through the history of New York City like one of those freshwater springs beneath the Manhattan asphalt.

Kevin Dann’s new book, Enchanted New York: A Journey Along Broadway Though Manhattan’s Magical Past, looks to bring this idea to a wider audience. The book is a kind of travelogue of the city’s magical places and events, demonstrating that from the American Revolution to the Red Scare of the 1950s, “both witting and unwitting actors have engaged in magic, often with enormous historical consequences rippling out far beyond Manhattan’s shores.”

The question arises, at least for me, of what Dann means by “magic.” He means “mind over matter,” that the “subtle always and everywhere rules over the dense” (his italics). According to Dann, “spirit is the superior agent, so all activity that works directly with spiritual forces and beings is inherently magical.”

With such a vague definition, it’s not surprising that the author sees Manhattan as swimming in magic. He starts his journey with George Washington’s 1789 inauguration at Federal Hall. Apparently the first president himself was a magical actor with his frequent references to “Providence” and his friendship with the Marquis de Lafayette, who had a deep interest in mesmerism and “animal magnetism.”

It’s a stretch. Washington’s religious beliefs were on the milder side of deism, and Lafayette never could convince Washington to delve into mesmerism. Still, the digressions are fun. Another stop on the tour is 293 Bleeker St., where Thomas Paine lived a few grim years toward the end of his life. Paine, of course, loathed anything that smacked of “mystery, miracle, and prophecy”; but it is interesting to consider all these spiritual strains—Freemasons, Episcopalians, and diehard deists like Paine—all coexisting in the city at the same time. (I was also delighted to learn that Bleeker Street was called Herring Street in the early nineteenth century.)

For Dann, there is magic even in science. Samuel Morse, the prototype of the American scientific entrepreneur, appears not once but twice in Enchanted New York—his daguerreotype studio on Nassau Street and his Wall Street telegraph company office. According to Dann, early photography seemed magical to “rural Americans” and “native peoples.” As for the telegraph, which was arguably one of the most important inventions ever, it was apparently a mere “mechanical simulacra of clairaudience, clairvoyance, clairsentience.”

Moving uptown and through the centuries, Dann points out sites related to Freemasonry, mesmerism, phrenology, Swedenborgianism, psychometry, Rosicrucianism and anthroposophy. Which is all fair enough, as each had firm adherents in New York City, or very strong associations, as in the case of theosophy (in fact, the New York Theosophical Society-owned Quest Bookshop continues to do business at its 240 East 53rd Street location).

I also enjoyed learning about the preponderance of texts that were birthed in New York City—books like Art Magic, published in 1876 by Emma Britten, a medium of English origin who lived at 206 West 38th Street; and the famous Theosophist magazine The Path: A Magazine Devoted to the Brotherhood of Humanity, Theosophy in America, and the Study of Occult Science, Philosophy, and Aryan Literature, which in 1890 had an office at 35 Broadway.

There was plenty of New York magic in more recent times. The New Age text A Course in Miracles—famously popularized (some would say appropriated) by former presidential candidate Marianne Williamson—was started in here in 1976, when the voice of Jesus of Nazareth first came to Helen Schucman, a psychologist, in her apartment in the Beresford, at 211 Central Park West. (Maybe Jesus found it convenient for Zabar’s.)

Not every reader will be up for Dann’s imprecision when it comes to magic. But Enchanted New York is full of wonderful anecdotes, and personally I enjoyed seeing how many of these addresses were still extant. It’s a nice mental ramble in these claustrophobic times.

I’d leave it there, but there’s a significant blind spot at the heart of this book. Enchanted New York is, by design, a patchwork history of American spiritualism. But it’s supposed to be about magic. Thus I found it mystifying that Dann’s magical New York is distinctly white and mostly devoid of the magical iterations of minority religions like Catholicism and Judaism.

To be fair, the introduction discusses the 1712 Slave Uprising, and the African Burial Ground at the corner of Broadway and Duane Street, where many were buried with what appear to be magical devices—“iron spheres, quarts and round disks,” a “string of blue and gold beads and cowrie shells.” And the only truly startling fact in the whole book comes when we learn that “every fifth person living in the city in 1789 was a slave.”

But Broadway started as a Native American path. Lower Broadway wasn’t far from Five Points, the nineteenth century home to poor Irish, Italians, and Blacks. It runs through Little Italy and Chinatown. It runs only a few blocks from the former Jewish enclaves of the Lower East Side or the Irish one of Hell’s Kitchen. Broadway runs through Black Harlem and Spanish Harlem. All these communities, religions, and ethnicities have their own folk-religions and magic. But their sites are invisible in this Grand Magical Narrative.

One final point. Aside from vague references to New York City as a “magnetic center,” Dann doesn’t explain why the history of Manhattan is braided with the supernatural. But I’d venture a simple explanation that hearkens back to what I wrote above—that Manhattan is the place where, since Henry Hudson first sailed by, people come to turn a buck.