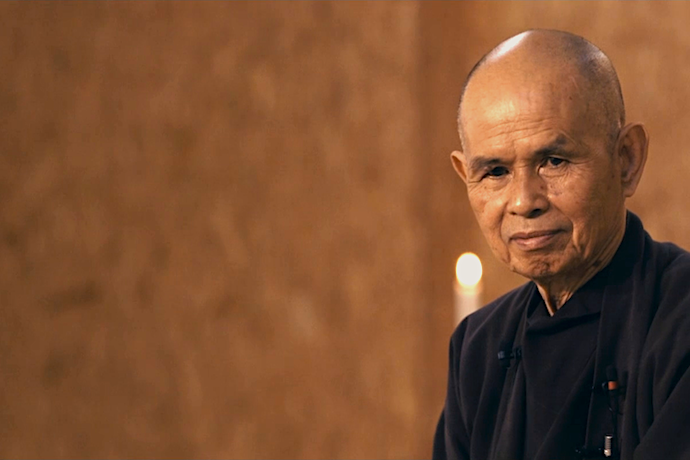

Thich Nhat Hanh, the Vietnamese Buddhist monk who joined the ancestors earlier this year, was profoundly influential for Black Buddhists who’ve struggled under the weight of systemic racism and intergenerational trauma. Thay (as he was affectionately known) coined the term “Socially Engaged Buddhism.” Black Buddhists have adopted many of his teachings and applied them to the specific suffering of living in a system of white supremacy.

Insight meditation teacher Devin Berry, co-founder of Deep Time Liberation retreats—which are oriented towards healing Black peoples’ ancestral trauma—reflects on the practice of applying Thay’s teachings to a context in which the legacies of historical slavery are still present. Indeed, while there are many differences between forms of Buddhism in the United States, in many ways the practices of Black Buddhists closely mirror the practices of Asian Buddhists, particularly with regards to devotional rituals to venerate ancestors and community.

Berry describes how Thay’s commitment to honoring ancestors within a Buddhist practice of deep listening was formative as Berry participated in rituals during meditation practice. “I’ve always felt a deep sense of spiritual urgency to engage the ancestral realm,” Berry says. “There was a flavor of sorrow and of strength that I felt within me growing up, and it felt like it ran through my family across generations. My Grandfather called himself the ‘KinKeeper,’ one who gathers the family in all manner of ways. That’s me now, only I gather the ancestors. I gather by deep looking and listening. I learned this from Thay’s teachings.”

Berry uplifts these ancestral practices within Buddhism as foundational for healing intergenerational trauma in the African diaspora, in lineages of families torn apart by the Transatlantic Slave Trade, the auction block, and the Great Migration. Indeed, Buddhism provides teachings and practices that facilitate turning towards suffering and learning how to stay present with the trauma that has arisen from fractured families, secrets, and lack of connection and information.

For Berry, the practices taught by Thay, which emerged from the context of being exiled from Vietnam during the war, are relevant—indeed vital—in a U.S. context. People of African descent still suffer the intergenerational trauma of slavery, Southern and Northern segregation, mass migration, persistent poverty, and mass incarceration in the present day.

The particular suffering of Black people has fueled the desire for dharma teachers such as Berry to make Buddhism relevant to Black communities. Uplifting the celebration of ancestors is central to this work. Berry’s own process of making Thay’s teachings known to Black people has evolved from his own journeys to Southern plantations in Virginia and the Deep South. Berry speaks of how his commitment to ancestral practices grew during a retreat with Thay, in particular during a “Touching the Earth” ceremony. Berry says: “I resonated with bringing in all of these folks that were my family, historical people, including abolitionists, suffragists, and spiritual ancestors.”

For many years, Berry embraced the “Touching the Earth” ceremony as a daily practice. The deep bow that’s central to the ritual felt like “completely giving myself to the ancestors and the earth.” Berry describes this prostration as a heart-opening, humble practice that aligned Buddhism with his African-American heritage in an embodied way.

In addition to embracing “Touching the Earth” as a daily practice, Berry traveled to Virginia, to the land of a friend whose family had owned a plantation, to engage in Tonglen (a practice that means “sending and receiving”),* “Touching the Earth,” and Vipassana (clear seeing). Thereafter, he went to a three-month retreat at Insight Meditation Society (IMS). He told me:

“Knowing that I now had the capacity and depth of practice to center blackness, to center the ancestors while the mind is quieting, the body softening, and the heart opening, and being able to practice directly with all that comes into my purview, was profound. I discovered that I am my own healer. That was a profound shift in my life.”

Berry, who co-founded Deep Time Liberation retreats with Insight teacher Noliwe Alexander, now seeks to make ancestral practices in the tradition of Thay’s Buddhist teachings accessible to other Black people seeking to heal intergenerational trauma. Since 2017, he and Alexander, along with dharma teacher and psychotherapist DaRa Williams and drummer Rosetta Saunders, have offered twice-yearly retreats to people of African descent.

In DTL retreats, the Black body is embraced as a vehicle for liberation. Indeed, these three themes—healing intergenerational trauma, honoring ancestors, and uplifting the Black body as a vehicle for liberation—are consistently uplifted by Black Buddhists in the U.S.. Berry says that he’s cultivated the capacity to be present with every feeling that arises, as a result of his ancestral practices. He states directly:

“My ancestors are with me, to bear witness. I’ve practiced on the grounds of the places my ancestors were enslaved—the source of trauma—and flipped it. Those places are sacred to me. I honor my ancestors’ legacy. The sacred places have become an altar. There isn’t anywhere that I actually feel unsafe in ways I previously had, as I have my ancestors with me always.”

Berry’s experience of honoring ancestors and healing the trauma caused by intergenerational trauma—using the teachings of Thich Nhat Hanh—illuminates how the practices of Black Buddhists are indebted to the teachings of Asian Buddhists. And, as Black Buddhists establish retreats and organizations, their distinctive practices are becoming more visible, culturally accessible, and spiritually relevant to Black religious seekers.

###

*Tonglen refers to a practice in which a meditator breathes in the pain and suffering on a specific person and breathes out wishes for happiness, well-being, and health. It is fundamentally about an exchange of energy, in which a meditator intends to take on another’s suffering and subsequently fill them with joy, happiness, and peace.

This article was made possible in part with support from Sacred Writes, a Henry Luce Foundation-funded project hosted by Northeastern University that promotes public scholarship on religion.