The US has had to deal with a home-grown attempted coup for the past two years. This week, Germans awoke to headlines that gave them a taste of what their American friends felt on January 6, 2021 as Germany saw its largest anti-terrorism operation carried out by police in recent history. Three thousand police officers searched 130 sites and 25 people have so far been detained by law enforcement on suspicion of the attempted violent overthrow of the government.

Aspects of the plot—to storm the German parliament and take members hostage—seem to echo what some rioters had planned for members of Congress on January 6th. But while the German terror group was stopped before they could reach the steps of the Reichstag building in central Berlin on this occasion, their plans were even more extensive: For at least a year, as they had conspired to establish secure IT structures and communication channels, they conducted shooting drills, plotted the overthrow of the democratically elected government, and planned attacks on critical infrastructure like the power grid, in order to create civil-war like scenes. (Coincidentally, the power grid in Moore County, North Carolina had apparently been attacked just days earlier leaving around 40,000 people without power.)

That degree of plotting would be troubling in itself, to put it mildly. But there’s another aspect that makes these thwarted right-wing terror plans particularly frightening: This was no plot designed by your classical neo-Nazis: young, male, out of work, on the fringes of society. This was a terror plot planned by those the German media refers to as “the bourgeois center”—the middle of society—not its fringes. A judge and former MP, policemen and members of the military.

Pia Lamberty is a trained psychologist and the CEO of the Center for Monitoring, Analysis and Strategy, a German non-profit inter-disciplinary think tank which combines expertise on conspiracy theories, disinformation, antisemitism and right-wing extremism. She explains that many still have faulty preconceptions of what a right-wing extremist looks like or what part of society they belong to:

“There are many clichés about right-wing extremists. Often, these don’t represent reality: right-wing extremists are present in all parts and areas of society. To believe that academic credentials or a certain societal standing makes a person impervious to radicalisation is a fatal misconception and just plain wrong. We have to understand that right-wing extremism is part of society and emerges from all of its parts.”

Parallels to January 6th are visible here as well where the rioters were older and from a higher social class than most right-wing terrorists have been to date, according to a survey conducted by the Atlantic. The men and women who stormed the Capitol had well-paying jobs, were middle-aged—and a concerning number were former members of the military and law enforcement.

Many things about the attempted coup in Germany remain unknown, “especially regarding the groups’ specific plans and inner-group dynamics,” says Lamberty.

“However, several participants aren’t unknown to those monitoring right-wing extremism, and have been spreading conspiracy myths and narratives belonging to the sovereign citizens’ movement. Some of them made their world view public on social media. Often, this was not taken seriously, and the danger was underestimated.”

In their midst, the terror group had a special asset: a former member of parliament and sitting judge, Birgit Malsack-Winkemann. She had been reinstated as a sitting judge by the Berlin administrative court, after she had been suspended over her right-wing remarks while serving as an MP by the Berlin administration of justice.

Malsack-Winckemann once served as a member of parliament for the right-wing Alternative for Germany party, the AfD. The terror group had already distributed amongst themselves important government positions in anticipation of their success and Malsack-Winkemann was supposed to lead the new Department of Justice. She is an avid markswoman, according to media reports, owns several guns, and has been described as esoteric by other party members.

As a former MP, she also has intimate knowledge of the layout of parliament, which would have been crucial in an attempted storming of the Bundestag. According to the Tagesspiegel, Malsack-Winkemann urged the group to act on their plans to overthrow the government soon. The Landgericht Berlin—or Berlin’s regional court—has now suspended her permanently.

In addition to having an insider, the group has, according to investigators, strong ties to the “Reichsbürger” movement, a German version of the “sovereign citizens’ movement.” Both movements refuse to pay taxes or accept government authority, and have demonstrated a willingness to use violent force, as well as the belief in conspiracy theories. Reichsbürger believe that Germany, rather than being an independent country, is actually still governed by the United States; that it’s not a country but a company (I won’t go into the absolutely unhinged “reasoning” behind this claim).

In short: They wanted to overthrow our current government and establish a new “Reich.” The terror group apparently also wanted to renegotiate Germany’s post-World War II settlement. The suspects are connected to conspiracy theories of the QAnon-kind—once again proving that right-wing radicalization is a global phenomenon with little respect for borders. Two other suspects were arrested in Kitzbühel, Austria, and Perugia, Italy.

The groups’ alleged ringleader is a man named Heinrich XIII Prince Reuss (Heinrich XIII Prinz Reuß zu Köstritz in German) who had dreamt of becoming the new emperor. He belongs to the former ruling aristocratic family of Thuringia, one of the German states—meaning that his “hunting castle” near Bad Lobenstein was searched as well as his other properties. The terror group used to meet in the castle on several occasions, according to information obtained by the MDR Thüringen.

Reuss has been a known part of the Reichsbürger scene since he held a talk at the Swiss “world web forum” in 2019, during which he claimed that Germany wasn’t a sovereign state but a “commercial structure.” Reuss claimed that foreign powers—namely “the international financial interest” which includes the Rothschild family—had in fact instigated World War I in order to “end the monarchy,” a narrative that manages to push several prominent antisemitic conspiracy theories.

Reuss had already made headlines earlier this year when he attended a summer party with Bad Lobenstein mayor Thomas Weigelt, who then proceeded to physically attack a reporter who tried to film him and Reuss together. Reuss is also accused of having tried to contact Russian government officials to support his political project.

Nuremberg 2.0

The German Verfassungsschutz (Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution) estimates in a 2021 report that 21,000 people belong to the “Reichsbürger” movement, of which it categorizes 1,500 as “right-wing extremists.” The report counts 2,100 people as “ready to potentially commit violence,” referring to known actors in the scene who have committed violent acts in the past or are known for violence-inciting speech.

The number of crimes committed by Reichsbürger has risen over the last couple of years, reaching 1,011 in 2021, including 184 violent crimes, and 500 currently own weapons legally. In 2016, a “Reichsbürger” shot and killed a police officer. During a protest against Covid-19 restrictions in 2020, several people managed to enter the Reichstag building of the German parliament and hundreds with ties to the “Reichsbürger” were arrested.

The terror group seems to have followed prominent QAnon beliefs of the “Deep State.” According to Lamberty, the timing of the attack is no coincidence:

“Especially during the pandemic we could see an increase in the number of sovereign citizens and a merging of their milieu with QAnon. Conspiracy theories like QAnon carry with them a strong potential for radicalisation: They suggest that the individual is partaking in a fight against allegedly evil forces. QAnon is very compatible with the Sovereign Citizen milieu. Both ideologies see the democratic state as illegitimate, both believe an underlying conspiracy is at work. Unfortunately, right-wing extremism is often not understood in its modern forms. Especially when a conspiracy narrative is central to an ideology, people often wave it off as ‘crazy’ instead of taking the dangers that emanate from these ideologies seriously.”

And according to reporting by Die Zeit, one of the suspects posted in a Telegram channel on Wednesday morning (shortly before the raid):

“Everything will be turned upside down: the current public prosecutors and judges, as well as the heads of the health departments and their superiors will find themselves in the dock at Nuremberg 2.0.”

This, of course, is hinting at mass executions, referring to the Nuremberg trials, which led to the sentencing and executions of prominent Nazi war criminals. “Nuremberg 2.0” has become a popular cipher during the pandemic amongst Covid-deniers, who use it to both relativize the Holocaust and threaten their perceived enemies—doctors, politicians, public health officials, hospital staff, and journalists.

Many, including a former military officer arrested during Thursday morning’s raids, have been openly calling for a “Nuremberg 2.0” for months. But since there were no consequences they felt safe enough to spread their violent fantasies of tribunals publicly.

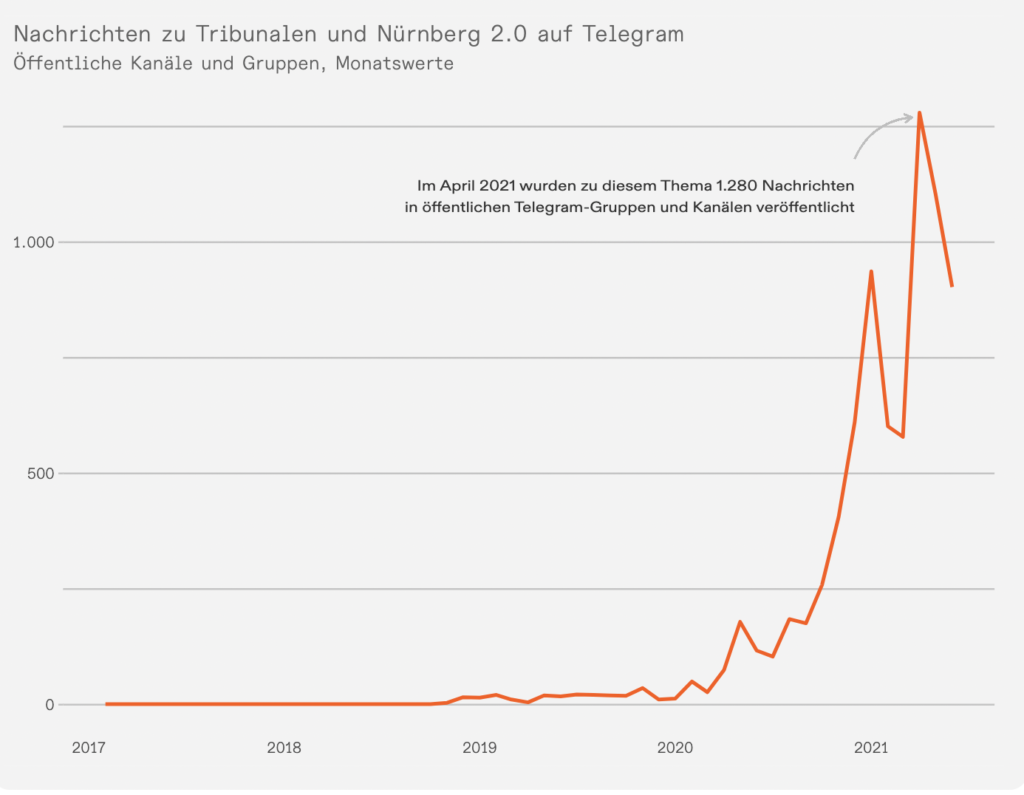

The think tank CeMAS notes an immense increase in use of “Nuremberg 2.0” in monitored Telegram channels since 2019, reaching a peak in April 2021 with 1280 messages that contained mentions of “tribunals” or “Nuremberg,” which are closely related to the Sovereign Citizens’ movement:

Source: https://cemas.io/blog/nuernberg-2-0/

A publication by CeMAS analyzes the connection of “Nuremberg 2.0” to one of the central sovereign citizens’ websites in their report:

“Since 2012 the website staatenlos.info mentions ‘Nuremberg 2.0’ as a necessary step ‘in freeing Germany and Europe from fascism and Nazism via the establishment of the SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) and SMAD (Sowjetische Militäradministration in Deutschland) courts of law with international law enforcement for all Nazi- and war criminals by the Allied High Commission.’ By fascism and nazism, staatenlos.info is referring to the Federal Republic of Germany. According to them, Germany is a ‘fascist colony,’ that needs to be de-nazified by Russia on the basis of national socialist laws, in order to answer the ‘German question’ and to re-establish a ‘German homeland.’ The ‘German question’ means the territorial unity of Germans in the form of a state and is a central topic in the sovereign citizens’ milieu, especially amongst ‘Reichsbürgern’.”

Because the “Reichsbürger” don’t accept the constitution or the laws of the Federal Republic of Germany they’re easily led to the fringe as their ideology gives them the permission structure to use violence. To them, the current government is illegitimate, an occupying force, so to speak. Violence is justified in its removal, which is often framed as self-defense or the liberation of the German people. Like QAnon adherents in the US, some Reichsbürger have stood trial for murder and attempted murder.

During the pandemic, the Reichsbürger milieu attracted more people than ever before, with their vocal opposition to the government’s public health safety measures to stop the spread of the pandemic. The pipeline between anti-vaxxers, esotericists and right-wing extremism can be very short, as the previous years have shown.

Inadequate denazification

You may still wonder how this could have happened. These events might seem especially bizarre from an international perspective, which might view Germany’s attempts to come to terms with the horrific history of and its role in the Holocaust as impressive.

However, all too often, this reckoning with the past has remained somewhat superficial. Some anti-Covid-measure protestors, for example, wore the star of David, effectively claiming that anti-vaxxers are as persecuted as Jews had been under Nazi rule—a clear relativization of the Holocaust. Many conspiracy theories around the vaccine have an antisemitic core, as does the German word “school medicine,” which was used by the Nazis to discredit what they referred to as “Jewish”—or evidence-based—medicine.

Evidence-based medicine was unpopular amongst those who favored a bogus “race-science”—hence their enthusiasm for exploring “alternative” medicine, such as homeopathy (which has no effect apart from the placebo effect), which is still very popular in Germany today. Homeopathy, experts warn, can be a vessel for anti-vaccine sentiments and a gateway to the far-right. And yet, to this day, it’s subsidized by the German health care system, with a whopping 6.7 million Euros in 2020 alone, although the minister of health is investigating whether this should be the case in the future. In parts of German society, pre-existing esoteric beliefs form a fertile ground for far-right recruitment—particularly in trying times like a pandemic.

While the “denazification” of German institutions was enacted through the Allies, it turned out not to have been extensive enough. This was mainly due to practical reasons: Their anti-fascist impetus had to be balanced with their simultaneous attempt to prevent the administrative state from collapsing, in order to not further destabilize an already volatile political situation post-war.

Therefore, a lot of former Nazis who weren’t in the high command or very public figures got away with a slap on the wrist, or were able to return to their positions after a while, leading to a continuum of right-wing ideology being represented in many German state institutions, especially in and around law enforcement. German law enforcement has long had a problem with reactionary elements whose actions tend to get played off by conservative and even centrist German politicians as “isolated incidents,” or the so-called “Einzelfälle.”

Within the last three years, security agencies have counted 327 instances of far-right incidents within the German police, the military and the Verfassungsschutz (Federal office for the protection of the constitution)—a number three times higher than under the previous administration’s report. The latest report also details ties to the Reichsbürger milieu. Experts attribute the stark rise in numbers to a heightened awareness and the agencies’ attempts to reduce the number of unreported cases.

The conservative Minister of the interior of the previous Merkel administration, Horst Seehofer, had always refused to conduct a study of right-wing sentiments in the police and military, in spite of the warnings of social scientists who urged him to commission one. For years, Seehofer claimed falsely that there was no “structural problem” regarding right-wing elements within law enforcement, although the “isolated instances” kept mounting.

The head of the Militärischer Abschirmdienst (Military Counterintelligence Service, MAD) of the Bundeswehr had warned in 2020, that the military had been infiltrated by right-wing elements, naming 600 pending cases where suspicion of right-wing sentiments was being investigated. The military’s special operations unit in particular, the “Kommando Spezialkräfte” (KSK), had been under investigation; 20 soldiers were under investigation recently, while the total number of suspected cases within the KSK amounts to 50.

Be it Nazi symbols on police seats, far-right messages in secret chat groups, swastikas, or Hitler imagery—again and again politicians claimed that German law enforcement and the military had no structural problem with far-right elements. For years, journalist and researcher Dirk Laabs warned of potential future terrorist attacks by highly trained soldiers. Two years ago, he told Deutschlandfunk:

“There have been early warnings since the 1990s. Back then, the MAD, which is supposed to make sure that no extremists join the ranks of the Bundeswehr, said: Special operations are particularly attractive to right-wing extremists, because they feel safe there, they have a structure, and because they can live out their beliefs that they’re better than everyone else. It makes sense to check closely that you don’t recruit the wrong people for this.

But there’s another problem when you consider a unit like the KSK: You’re asking the people in it to do extreme things (…) Officers told me ‘you can’t be surprised that there are unstable people amongst them, that’s what we want: people who do what normal people wouldn’t.’ Meaning: constantly risking your life under extreme circumstances abroad. That means that, for years, no one looked closely when it came to the selection of candidates for the unit.”

According to investigators, the conspirators were willing to use violence to achieve their goals, including murder. Their organization seems to have split into a “Rat” (Council) which was responsible for the organization and a “military wing” which was supposed to violently overthrow the government. The military wing seems to have been led by a former colonel who once belonged to the Fallschirmjägerbataillon 251 in Calw, which changed from an elite group of paratroopers to the special forces unit “KSK” in 1996.

According to the Süddeutsche Zeitung, he was suspended from the Bundeswehr after a violation of gun laws. Another current member of the KSK’s logistics unit was arrested by the special forces unit of the police, the GSG9 anti-terror-unit, which also searched the KSK’s premises.

Both-sides-ing a coup

The public debate in Germany during the last couple of weeks had been dominated by conservative, right-wing and centrist politicians trying to whip up a fear of zealous, but peaceful climate activists belonging to the group “Last Generation.” Conservatives had warned of what they called an emerging “climate RAF”—referencing the “Rote Armee Fraktion” (often referred to as the “Baader–Meinhof Gang”), a left-wing terror group responsible for the destruction of property and a number of deaths in the 1970s.

While teenagers were gluing themselves to the street in a desperate cry for climate justice, right-wing terrorists were plotting the overthrow of the German government and the execution of their enemies. Their preparations took at least a year—and included the establishment of a secure IT infrastructure, shooting exercises, the procurement of weapons and the recruitment of members from the ranks of police and the military.

It seems unlikely, however, that conservative forces will see reason when it comes to their lack of awareness regarding the clear and present danger of the far-right. The editor-in-chief of the conservative newspaper “Die Welt” wasn’t deterred by this close call: Within hours of the nationwide arrests, after the biggest anti-terror-raid in the nation’s history, he published an op-ed that only required two sentences to arrive at both-sides-ism, claiming that there is “brutalization and conspiracy thinking (…) not only on the right.”

Germany has a right-wing extremism problem—and it’s essential that law enforcement agencies and politicians finally take it seriously. Because this was simply a warning shot. For now, bloodshed has been prevented. As for the pundit class: If an attempted overthrow of the government isn’t enough to make them reconsider their stances, nothing ever will—whether in the US or in Germany.