In The Family (now also a Netflix series), journalist and author Jeff Sharlet wrote about his experience of going undercover as a young man in a secret, elitist organization of the American Christian Right. It was, in many ways, the opposite of his latest book, The Undertow: Scenes From a Slow Civil War.

The Undertow: Scenes from a Slow Civil War

Jeff Sharlet

W. W. Norton & Company

March, 2023

We tag along as he learns about the violent symbolism of the all-black American flag; visits Lauren Boebert’s infamous “Shooters” restaurant (where waitstaff carry guns); speaks to people who’ve turned their unprocessed grief into anger and violence; and listens to sermons that speak of a coming war.

Having met Jeff in person for the first time a year ago when we sat on a panel at a conference on White Christian nationalism at Yale University, I was curious to get a sense of what it was like to spend months traveling the country searching for the ghost of an insurrectionist, chasing down fascist flags, and knocking on the doors of the people displaying them in an effort to understand what lies beneath.

The following has been edited and condensed from a pair of conversations that took place over a two-week period.

When did this meditation on a brewing civil war begin to take shape in your mind? And how does one choose the best travel route when following an insurrectionist’s ghost?

This broad movement that we might describe as Christian nationalism is very complex and filled with many tributaries. That was the backdrop. So some of the early pieces in the book are from that work in its different forms—and when Trumpism comes down that golden escalator in 2015, he is a figure that I recognize instantly as the “Strongman” of the sort that American fundamentalism has exported: The dictators that we’ve propped up in the Philippines and Somalia and Indonesia.

And here it was. We’ve had extreme right-wing politicians. But not that kind of figure who combines buffoonery and menace. That’s an alert that now we’re moving into what I understand as fascist aesthetics.

So I started paying attention to that, because I was frightened and fascinated. I think I started understanding that this was going to be a book in 2018, and that I was going to bring these strands together, through that metaphor of “the undertow.” People are saying, “Where has Trump come from?” Well, we’ve been headed there for a while.

Much of the book takes place after January 6th, 2021. I had a destination—Sacramento, California—to attend a rally for Ashley Babbitt [who was killed by a capitol police officer during the January 6 insurrection and who has since become a martyr on the Right]. And then I drove east. I think of the ways in which some people say: Why did you choose to speak to all these people? Because they were [right] there. We don’t have to go looking under rocks. This is the mainstream now.

For a long time, you didn’t use the word “fascism” to describe the movement that we’re seeing. What made you change your mind?

So in 2008, I wrote this book called The Family, and there’s a chapter called “The F Word”—the F word, of course, being fascism. That chapter is not about the contemporary moment of this Christian nationalist organization, which is the oldest and arguably most influential in Washington. Its focus is mostly global and international. Where I really had to contend with the Family’s fascism was in the postwar era.

The organization was founded in 1935, but in 1945 they immediately started recruiting senior Nazi war criminals. There’s one, Ulrich von Gienanth. And I wonder—do these guys show up in the New York Times? [It turns out that] their deportation made banner headlines. They were running the SS operations in the United States, probably participating in far more extensive sabotage within the United States leading up to the war.

Then, much more contemporary memory hits: Nazis were blowing shit up in America and recruiting folks. That’s who this organization brought in. Well, the Family didn’t bring von Gienanth in to advise U.S. congressmen because he wasn’t allowed into the United States, so they brought the U.S. congressmen to Germany for von Gienanth’s great insights. Now, how do I say that’s not fascism?

The Family to this day says, to understand Jesus, look at Hitler, look at Stalin, look at Mao. What they liked is authoritarianism and strength. They said Jesus is an iron fist. The particular nature of the iron fist—is this a fascist fist?—not as important. And in fact, in that book I argued that fascism was impossible in the United States. Even saying that now makes me cringe. It wasn’t.

Look, fascism has always been present in the United States. We know that the Nazis drew on the American example. There were elements of it, but it was impossible as the reigning full-on paradigm. The experience of so many communities of color was one of living under fascist control. So many sheriffs in their counties ruled with fascist power, but a full-on fascist government? No, we weren’t going to get that. And the reason was the same thing that makes the United States unusual amongst developed nations. Our particular devotion to God.

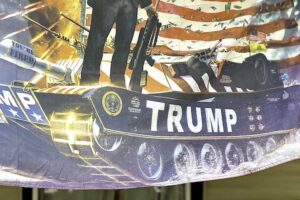

Trump banner. Jeff Sharlet/Twitter

And some people may ask, oh, isn’t that super Christian nationalist stuff just fascist? Well, it used to get in the way of actual fascism. As I understand it from the scholarship that I read, one of the hallmarks of fascism is a cult of personality. And that cult of personality isn’t just a figurehead, it’s a license. You need that earthly avatar of this absolute power—that Übermensch, I guess, if you will—in order to license all the Hitlers, all the little Trumps, a million little Trumps. And so that was my argument; I said they would not switch out father for the führer. And I was wrong.

When did you realize you were wrong? That fascism was not impossible in the US?

In 2015, when we watched Trump come down the golden escalator. This is the strongman that the fundamentalists I’ve been writing about have supported in Indonesia and Brazil. And Guatemala. And Honduras. And the Philippines. And Uganda. The reality is, George W. Bush and George H.W. Bush, both of whom I marched against—I got beat up by cops because I was so furious about what they were doing in the Middle East in particular—they were not fascists. They were imperialists. And there’s more than one kind of bad under the sun. I might still argue to this day that George W. Bush’s place in line to hell is in front of Trump’s (may the dead haunt him). But it wasn’t fascist.

And when Trump came down the golden escalator, that was the fascist aesthetic. Because until then, in America, even with Reagan, we didn’t quite have the cult of personality. We had the founders, we had the myth, and we had violence. We had so much violence. But we believed in ourselves: A peaceful city upon a hill. Well, the violence of Trump was [about] pleasure. It still is. And, as I argue in The Undertow, it’s a cult of militant eroticism.

What’s your response to the sixty-four thousand dollar question so often asked since his arrival as a viable candidate: why do evangelicals still like Trump, despite being a thrice-married, gleefully vulgar man who is open about his multiple affairs?

I’ve been around these folks enough to say: Boy, do they like talking about sex a lot. The sex you shouldn’t have is one of their favorite topics, along with exactly the way to the sex you shouldn’t have—and they can go into detail.

This tracks with my experience of reading evangelical marriage advice and dating books for research purposes. They’re full of sex, and for those who aren’t familiar with the culture, it’s surprisingly explicitly sexual. But then—is it really surprising? Isn’t sex inherently part of the human experience? Why should that be any different for evangelicals, why should that be any different for the fascists you met on your travels?

I think this is the failure when we consider these fascists the other. As a writer, I always start with the body. Remember the body. I also always say that I’ve never had an original thought in my life and I never will. And what a blessing! Because it means anything I’m thinking someone else is too. I’m never alone! If I ever have an inappropriate sexual thought, everybody else has too. That includes evangelicals, right? And Trump gave them license. He gave them license for the inappropriate sexual thought. He gave them license for the fascist thought.

The first time I saw how this fascist aesthetic and the license were received, was in 2016 at a rally in Youngstown, Ohio, a former steel town. Youngstown is a post-apocalyptic place. There’s nice things there too, but there is true devastation. And from this devastation, the crowds of Youngstown—not just White, by the way—had waited for hours for Trump to come.

I remember this from the book—you’d been chatting with this elderly couple as they waited for Trump to appear when, suddenly, violence entered what had been a pleasant conversation.

And then, this Grandpa says: “I can’t wait to get a hold of a protester so I can beat the shit out of him and get on CNN.” His wife, bedecked in turquoise jewelry, says: “Oh, Jean.” And I thought: She doesn’t like this. And she smiles. It’s like this intimate moment between them. And then she leans into me—this is weird shit, okay? This is like a threesome, right? They’re pulling me in. She’s got one hand around Jean, and now she pulls me in and she whispers in my ear something very vulgar. I don’t think she’s spoken like this most of her life. She hates Hillary. She says: “Don’t she look like she’s been rode hard and put up wet?” I recently published a portion of that stuff in the New York Times. And we had a lot of debates about whether I could include that.

Really?

We eventually decided I could include that—because it was a reference to equestrian sports. [He laughs] Really. If we were very insistent that there was no sexual innuendo whatsoever… Certainly not! Just a saddle used and put away! It’s about the mainstream media and the things that it’s afraid to talk about.

So why have so many mainstream media outlets been hesitant to use the word fascism? And since you changed your mind what kinds of reactions have you been seeing? Has it affected the way journalists from those outlets react to your writing?

A good friend of mine, the writer JoAnn Wypijewski, has a book called What We Don’t Talk About: Sex and the Mess of Life. She’s written about the ways in which we separate sex from politics. I’ve seen this in my own reporting about The Family, which nobody gave a damn about until a number of Family members started getting caught in affairs. You know, did they care [that The Family was] providing lists of communists to Suharto for the genocide? Or about total war in Somalia?

I remember a producer saying to me, and I kid you not: “What’s a Somalia?”

What’s a Somalia?

But! Oh, he had sex with someone he wasn’t married to! Who? Tell us more! We all have those prurient interests. So I think about this after that Youngstown rally—I go to the bar to get drunk, because I’ve just been at a rally that I realized was a fascist rally. And then I realized: the preacher had started but the press was sitting back there looking at their phones not paying attention. This the most right-wing preacher I’ve ever heard—he’s screaming [for] Holy war—and they didn’t cover it! And then they ask, where did the evangelical support come from?

So I go to the bar to get drunk. There’s some other people with the same mission. Amongst them, some former steelworkers. They hate Trump and they know Trump’s a racist, but they will vote for him, because he lies to them about the steel mills coming back. They know it’s a lie, but they’re like, What the fuck else do I have now? Let me find the part the Times wouldn’t let me include.

[Sharlet thumbs through his copy of The Undertow] I’ve decided that my new plan with this book is to burn all bridges. So that I can’t publish anywhere and I can live a peaceful life.

[Finds the right page] So they say, this is just inappropriate, it should not be in the paper of record, I don’t think this has anything to do with why Trump was elected.

I’m bracing myself.

So we’ve got these three guys in the bar, right? Yeah. One of them, the bartender, he can’t believe his friends are crossing over. [Reads from The Undertow]:

“Trump’s not just a racist. He’s a fucking psychotic racist!”

“So are half the people who walk into this fucking bar!” Shawn shouted back.

“But they’re not running for president,” said the bartender.

The bartender is from Youngstown and he’s holding down the fort for old Youngstown Democrats.

“OK,” said Shawn. “What about Michelle Obama? She’s a racist!”

“What?” said the bartender? “One—no, she’s not, and I don’t know what you’re talking about. Two, it doesn’t fucking matter, because Michelle Obama isn’t running for president.”

“Well,” said Shawn, grinning as he wound up what he considered a zinger, “she sucks the president’s c*ck, don’t she?” It was the essence of Trump’s rhetorical style: vulgarity masquerading as candor. That the accusation made no sense only made it, in Trumpian terms, more “perfect,” since, lacking any appeal to logic, it could not be rebutted. [Closes the book.]

No, [the New York Times] shall not have Michelle Obama and that other word together even in the vicinity of the paper—that is surely not part of Trump’s appeal. [Scoffs.]

And, since we’re talking about the hatred of the Obamas: You know what would’ve made Barack Obama [feel] a lot safer for the racists? If he wasn’t so just goddamn good looking, you know? If they didn’t know that some of the women in their lives are saying: that is a good looking man. And that some of the men (who would never say it) think: that is a good looking man. And then they’re looking at Michelle Obama; they call her a baboon, everything else. Why are they doing that? It’s the flip side of the lynching story, which is the sexualization of Blackness; Blackness is a threat to the innocent White womanhood of Ashli Babbitt.

And yet, at the same time, [they] imagine that Blackness is a sexuality [they] can hold at bay but occasionally peek at. And that comes to a head in the Omaha, Nebraska section where a White pastor claims he learned to preach in North Omaha Black churches, though he’s a full-on fascist Civil War preacher.

And I’ll say this—It’s like Elvis and Chuck Berry, right? Elvis rips off Chuck Berry. We know that. That’s settled. But Elvis is also pretty good, right? So this pastor, Hank, he’s pretty good at it. He can do it. He can preach. Which is why he has a very diverse congregation. And he makes it sexual.

With a background in researching German fascism, the encounter you describe at the Lord of Hosts Church in Omaha, Nebraska, was to me one of the most bone chilling ones of the entire book. Not only were you physically threatened—they threw you out of the church—but also because the inherent violence of the sermon, which is clothed in layers of plausible deniability and an onslaught of fascist kitsch, was intended to get listeners high on the ecstasy of fascism. Can you tell us about that?

So, Pastor Hank is talking about this church as a militia. Like more and more churches around the States, they don’t just support guns, they have guns. (At the Church of Glad Tidings in Yuba City, California, Tuesday night is militia-recruiting night.)

Lord of Hosts in Omaha, Nebraska. No fringe church; nice suburban megachurch. This is a diverse church and the pastor himself—pastor Hank Kunneman, he’s a White man. But he speaks of himself as a Black man.

Pickup truck. Jeff Sharlet/Twitter

I don’t mean that figuratively. He talks about “I was lost. I was a white man. I went to the black church and I was born again. The left think it’s theirs. It’s ours.” So suddenly, we’re in the space of remaking. And he says those men in the back, those men with guns, you know; why are they there? The church is armed because the angels are armed. But you can’t see the angels. So why do we need gunmen? So that you can see. Same reason why we have the cross, so that you can see.

They were the armed forces of this church by rod and staff. They honor the gun. Those men in the back, he says, let me explain it to you with Psalm 23. And then he says—and I didn’t put this in the book, and this is my regret—I tried to show not tell, and I should have told. He says, “thy rod and thy staff” And then he does a fucking Elvis hip thrust. Thy rod is thy gun and it is the phallus. It’s the misogyny that rules.

To them, the gun is the tool of innocence; so many of these armed men said, “the gun is the promotion of peace.” But it’s also simultaneously the transgression. That’s what the thrust of “Thy Rod” and the sexual innuendo of it means—the way that’s also the transgression of a White man who’s doing his best James Brown imitation. Because in that imagination, Blackness is a kind of sexuality, and Kunnemann possesses that potent sexual power in the same way that he claims he has a mandate for war. To take back the nation. And he does not mean that figuratively. (I didn’t include the whole sermon in the book.) He is openly saying “war is coming. We’re going to fight a war and we’re going to win.”

[The mandate for war] is given to him by two visions. One of Christ in combat fatigues and a tight white t-shirt. Again, not just militaristic but he’s sort of sexualizing the figure. But then, even more interestingly, he has a vision that the roof of the sanctuary lifts off and a Native American warrior with the biggest headdress he’s ever seen comes and hurls a spear—we’re talking spear of destiny here—hurls the spear at his feet and he takes up the spear. It’s the Indigenous man passing on the weapon to the White man who shall wield it for the nation.

This is to me the black hole, the gravitational pull of American fascism. I describe this in the book as the latest American contribution to fascism ( I say “the latest” because, as, scholars have noted, Hitler was borrowing from the United States when it came to racial purity laws). I do think that this is a White supremacist movement, but like our friend Anthea Butler says, it works through the promise of Whiteness.

And the latest American contribution to fascism is that it absolved fascism of its need for racial purity, which was necessary for it to succeed in the United States.

There’s another chilling episode in your book where you find yourself invited into the house of a militia leader who shows off his gun collection. What does this encounter reveal about the far-right ecosystem’s ability to hold contradictory views at the same time?

I think of meeting a militia commander named Rob Brumm. He was there [at the January 6 insurrection] and yet he says the whole thing was a hoax.

Simultaneously, I think of the Church of Glad Tidings. The speaker, a prominent sovereign citizen, says that Trump is still president. And that of course we all know that Trump’s the 19th president because all the others since [the 14th Amendment] have been illegal. And I’m looking around and it says 45 on his hat. Can this be? Yes, it can.

We’re starting to speak of that kind of evangelical and Pentecostal church experience where many truths can be simultaneously true, right? You can be White supremacist and—like Julius, who I met at the Ashli Babbitt rally—a Black man. Half the speakers at the Ashli Babbitt rally were people of color.

Rob Brumm is the leader of a White supremacist militia. Rob also considers himself Jewish. He did some ancestry and discovered that maybe he was Jewish, and that was exciting to him. His daughter most definitely doesn’t [agree]; she has a tattoo of a German flag with the iron cross. She is not Jewish. She’s very resentful of the notion that she would be considered a nazi because of that tattoo, but fully fascist in her views.

And Brumm says he’s against abortion, but it’s your own business. But we’re going to need Black bodies for the war with China, we can’t lose these Black bodies. We need our Black brothers in arms to be the frontline soldiers. This is not the purified White nation—Brumm opposes abortion because he has a delusional idea that it’s much higher in the Black community than it is amongst Whites. He wants more Black people for America.

Liberals and the Left, we’re so intent on the old model, the Ku Klux Klan model—which is alive and afoot in the land, but we can only see that. So we insist that this movement must be White supremacist. And it is White supremacist. But then we think, therefore it must be all White, so we don’t see the 30% of Latinx voters who turn to Trump, we dismiss the—whatever it is, four or five percent—of Black male Trump voters.

It seems like an oxymoron—but, as you noted earlier, scholars like Anthea Butler have argued that “Whiteness” is a promise of power, a promise of innocence. It hides behind “color blindness,” but that doesn’t make it less White supremacist. It allows for the cognitive dissonance of absorbing Black people and people of color into the movement as long as they are dedicated to upholding the structures of the White supremacist system.

The all-black American flag. Jeff Sharlet/Twitter

The most important thing to understand about how American fascism works is how it absorbs people of color. I write about a rally in Sunrise, Florida. You expect to see Cubans there, but you’ll also find a huge Venezuelan American community, a huge Nicaraguan American community, a huge Puerto Rican American community—all there for Trump. One of the most militant rallies I’ve seen. But elsewhere it inoculates everyone from the R-word: How can Kyle Rittenhouse be racist when some of his best friends are Black? How can we be racist when we love Candace Owens?

That’s exactly how Eric Metaxas introduced a Black pastor at a Jericho March rally before Jan 6th: they call us racists, but here is a Black pastor.

Yeah, [how can we be racist] when we might vote for Tim Scott! The fact that so many of these rallies went unremarked-on in the American press; so much of the book is trying to show that there are things going on here that you’re not paying attention to.

[It may be] Black or Latino pastors [who speak], but the crowd in Youngstown, Ohio is White.

I think the answer to all of these things is the “intersectionality of fascism.” That term, intersectionality, that we think belongs to the Left but, like so many, has been co-opted by the Right. Or accelerationism—this Marxist idea that right-wing intellectuals adopt, saying “Yes, you’re right, democracy is too slow. Let’s speed it up.”

What do you think are the core ideas we must grasp in order to understand the broadness of American fascism?

Is it Whiteness? Is it class? Is it gender? Misogyny? Is it the exhaustion of the pandemic? Is it screens? Is it climate grief? Yes, absolutely. The common denominator is grief, unprocessed loss—whether it’s the loss of privilege attendant to Whiteness, whether it’s real economic loss (which is there), or whether it’s the loss of a belief in the future.

Whether, like Ashli Babbitt, it’s the crushing debt that she’s in and the surging homelessness that she’s around, that she can’t understand. She lacks a structural language—a man defecates in her yard. She says I’m tired of compassion, I’m tired of swimming against the undertow. The undertow is drawing her out toward rage, which I can understand as a form of love. So the common denominator—from their perspective, love, from my perspective, grief—curdles into rage.

The undertow is not just going to drag you out. The undertow will carry you. And a lot of people are tired and they want to be carried. I say that with no sympathy—because that’s why [folk singers like] Harry Belafonte and Lee Hays are [so desperately needed]. You don’t get to be carried, right? The struggle is long. You’ve got to fight.

It drives me nuts that the American Left says “Is it motivated by race or class or gender?” Yes! In that answer, you hear it all. “Thy rod is thy gun” with a hip thrust—that is the intersectionality of fascism. I hope there’s enough about the militant eroticism in this book for people to understand that.

That’s something I really noticed when I read your book. When it comes to religion, ecstasy has always been a theme. But I found it striking how intertwined violence and sexual pleasure are here. By the way, we’re going off on a tangent, but I think this might be interesting to you. As a joke, I started a project with a colleague of mine for which I had to read this Trump romance novel. The series is called Maga Hat Romance. Then we do a feminist analysis of them in a podcast.

[Googles it.] MAGA Hat Romance by Liberty Adams!

Yes, exactly. And doesn’t the guy on the cover look just like [former GOP representative] Madison Cawthorn?

I’m just seeing it—oooh wow.

We read Christian romance novels to decipher what they convey about love and relationships. And it’s disturbing how closely linked very graphic descriptions of violence are in Christian romance novels with sex. It really shows that the fascination with the flesh—what you can do to human flesh, be it through sex or through violence—is really at the core of this.

Oh, I’m going to write that down. That’s a very good line. The fascination with the flesh and what you can do to the human flesh. And when you frame it like that, it really erases the distinction between hate and love. Ashli Babbitt, her first tweet is hashtag Love and Trump. But she tweets it at a point where her anger has become this ecstatic pleasure of anger as love. And to go back to that question of using the term fascism, the reason I did is partly the cult of personality that licenses it, but also the pleasure in violence, the fascination with the flesh and what you can do with it.

It’s still, to this day, not much reported on. Trump spends so much time describing sex crimes and murders. He doesn’t just say “Isn’t it terrible that this happens?” I write in the book about a particular rally where he went on for 20 minutes, describing decapitations, disembowelments, a “bad hombre”—a Brown man—crawling through a broken window while a traveling salesman is away. Which is also the sort of fascinating riff, the traveling salesman. Do these still exist? I think the last time I heard of a traveling salesman was when I was 13 and I found this magazine by the river.

It’s the pornography and the fantasy life that he grew up on. It’s about what could happen, right? It could be sexual, it could be violent. It could be a decapitation. That includes death, that includes their fascination with it, which is another element. I think this brings us across the border from authoritarianism or neoliberalism into fascism. Neoliberalism is violent. But it doesn’t celebrate and revel in violence. Neoliberalism is abstraction. Fascism is a kind of fever dream, corporatization.

If you try to put it into a picture, when it comes to fascism, the jackboot relishes in anticipation of the crushing of the skull, essentially.

And the jackboot is shiny. And I say this as a writer—you know, that’s the nature of my writing. I’m attracted to shiny things. I don’t actually like going to Trump rallies, because I don’t like going where other reporters are—but they weren’t actually there. They stayed in a metal pen. So I could roam and I would be the only person there. To Ashli Babbitt, there was solace and comfort [at Trump rallies]. This is comfort, chaos, solace of the surreal. I don’t share it, but I have felt it. And I think that the reason I haven’t indulged in it is—because we make an effort [not to].

People who become captive to pornography, the incels and men’s rights activists—they never enjoy romance and sex with women they claim to desire. Elliot Rodger, the so-called “supreme gentleman” and wealthy, smart guy, couldn’t get the Barbie Doll girlfriend he thought he deserved. And so he goes and kills many people instead.

I think one of the arguments of the book, and especially with Ashli Babbitt, is that they’re experiencing this great relief and pleasure—What if I stop trying to be good? Stop trying to free myself? They know that Michelle Obama isn’t a racist and that their vulgar shit has nothing to do with it. But it feels good. It’s the gross thoughts. What if, what if, instead of trying to set myself free to organize with others to make a new Youngstown… What if I just stayed in the dark? It says a lot about the love of the strongman. The way the guns, a weapon, make you feel something.