In February 2023, Tenzin Gyatso, the 14th Dalai Lama, appeared in Dharamshala, India at an event sponsored by the M3M Foundation, a philanthropic initiative established by the M3M Group—real-estate developers committed to “magnificence in the trinity of men, materials, & money.” By April, this local event had sparked a global controversy. A video clip from the event shows a boy of about 7 or 8 asking to hug the Dalai Lama, after which the Dalai Lama tells the boy to suck his tongue. Released into the online ecosystem, the video predictably went viral, launching a heated debate.

Supporters rushed to the Dalai Lama’s defense, noting that his actions were normal within Tibetan cultural practices and that the video was promoted by Chinese agents and sympathizers in order to impeach his character in the West. Indeed, according to Vice, professor of China studies Timothy Grose believes that “the interaction is being weaponised by sympathisers of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).”

In other quarters, accusations of pedophilia, “grooming,” and sexual assault flooded comment boards. In a matter of days a globally recognized religious figure is reincarnated in the public perception as a sexual predator; yet another man whose sexuality had been warped into something pathological by the toxic combination of religious authority and institutional celibacy.

Online siloed constituencies quickly materialized around the dueling hashtags #IStandWithDalaiLama and #DalaiLamaPedo. Whatever the truth may be—how that boy experienced his physical encounter with the 14th Dalai Lama or what his intentions were—the controversy demonstrates the long-standing practice of constructing the Dalai Lamas according to the cultural and political prerogatives of the West.

It was not so long ago that the cause of Tibetan independence and its avatar, the 14th Dalai Lama, were celebrated by influencers of the old technological regimes, cinema and popular music. Between the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the end of apartheid legislation in South Africa, the early 1990s were heady days for the democratic West. It was in this moment that the Dalai Lama and awareness of the so-called “Tibet question” exploded into mainstream Western awareness. In 1989, the Dalai Lama received the Nobel Peace Prize “for advocating peaceful solutions based upon tolerance and mutual respect in order to preserve the historical and cultural heritage of his people.”

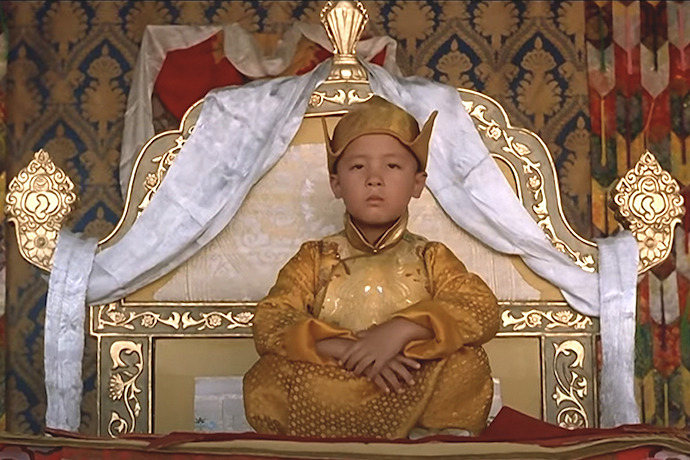

Seemingly overnight, this religious figure exiled from a remote Central Asian territory was mixing with the Western glitterati. He was the subject of two Hollywood feature films, both released in 1997. Sony Pictures released Seven Years in Tibet, starring Brad Pitt as the Austrian mountaineer and member of the Nazi SS Heinrich Harrer, who discovers the joys of fellowship and fatherhood through his friendship with the child Dalai Lama in a utopian Tibet. Buena Vista Pictures released Martin Scorsese’s opus Kundun, a lavish and politically pointed biopic based in part on the 14th Dalai Lama’s autobiography, My Land and My People (originally published in 1962 but revised and republished in 1997), punched up into a screenplay by Melissa Mathison.

The same year, New York City hosted the second Tibetan Freedom Concert, a benefit to support Tibetan independence spearheaded by Adam Yauch (aka MCA) of the Beastie Boys. The inaugural concert in San Francisco the year before drew 100,000 people and featured some of the biggest names in music at the time: Yauch’s Beastie Boys, Rage Against the Machine, Smashing Pumpkins, A Tribe Called Quest, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers. The films and concerts spurred the growth of the Students for a Free Tibet youth movement and shaped awareness of the Tibetan political cause and the 14th Dalai Lama for a generation. Who among those youthful Gen Xers earnestly grooving to the Beastie Boys’ “Bodhisattva Vow” or the Chili Peppers’ “Suck My Kiss” could have foreseen the current controversy?

There is, however, another—much longer—timeline against which to consider the current controversy. For centuries, Western perception of Tibet, Tibetan Buddhism, and the Dalai Lamas was subject to the now moribund technology of print. With a curious consistency, Tibetan Buddhism and the Dalai Lamas were represented as Asian corollaries to the Catholic Church. Jesuit observers like John Grueber (1623-1680) saw a distorted mirror image of themselves in Tibet, reporting that Tibetans celebrated Mass with bread and wine, blessed married couples, gave extreme unction to the dying, set up nunneries, and consecrated Bishops. Tibetan Buddhism appeared as a demonic doppelganger of the true Catholic faith, a perverted version of the truth, complete with its own devilish Pope, the Dalai Lama.

Protestants likewise perceived and represented Tibetan Buddhism according to their own image of Catholicism, which was of a corrupt Christianity sunk under with superstitious ritual and priestcraft. Projecting their own self-image, Protestant authors such as Laurence Waddell (1854-1938) cast Tibetan Buddhism, with its own “priesthood,” as a superstitious deviation from the authentic original—a corruption of the rational, moral teachings of the Buddha. The perception of an equivalence between Tibetan Buddhism and Catholic Christianity has proven to be remarkably resilient. To this day, the Dalai Lama is understood in the popular imagination as being the Buddhist Pope.

Needless to say, the Dalai Lamas are not a Tibetan corollary to the Bishop of Rome (they aren’t even promoted to the position from the clerical ranks). The Dalai Lamas are not the authoritative leaders of Buddhism as a global religion or even of Tibetan Buddhism as a regional iteration of Buddhism. Tibetan Buddhism consists of multiple schools, but the Dalai Lamas aren’t even the head of their own school of Tibetan Buddhism known as the Geluk (or Gelug).

The Dalai Lamas are tulku, each identified in their youth as a reincarnation of the previous Dalai Lama and raised and trained accordingly within the monastic institutions of the Geluk school of Tibetan Buddhism. The Dalai Lamas are also manifestations of Chenrezig, a bodhisattva incarnation of the Buddhas’ infinite compassion, progenitor of the Tibetan people, and patron deity of Tibet. According to one interpretation, Chenrezig appears in the world to slake the suffering of benighted sentient beings who are able to experience him only according to their own ignorance-driven faculties of perception. In other words, one perceives Chenrezig’s manifestations according to one’s own karmic propensities.

At a cultural moment in the West inflected by public awareness of the sexual abuse of children by Catholic clergy and its coverup by the Church; when systemic abuses within the Southern Baptist Convention have come to light; and when false pizzagate pedophilia conspiracy theories and incel panic ricochet in media echo chambers; it feels almost inevitable that the 14th Dalai Lama would be understood by many as a sexual predator. Yet whether we see the 14th Dalai Lama as a democratic champion for human rights struggling to preserve the political and cultural autonomy of Tibetan peoples or whether we see him as the sexually twisted product of anachronistic and abusive religious institutions, we perceive him according to the karmic propensities of our own political and cultural moment.