Over the past few years purity culture has become a hot topic in the secular press. The harm it inflicts on White women has been explored by a number of scholars and survivors in books (both popular and scholarly), on TV, in movies, and elsewhere. But one aspect of purity culture that remains largely unexamined is the way that it’s woven into many of our national myths about a pure White race—myths that have fed White supremacy in the nation’s past and continue to do so today.

Sara Moslener, who’s been studying evangelical purity culture for over 15 years, noticed this gap during interviews with BIPOC individuals who’ve lived through it, and explores these histories in her new podcast Pure White, which trains its focus on evangelical purity culture as a racialized concept.As a queer woman who studies the effects of purity culture on LGBTQ+ youth I was eager to sit down with Moslener to learn how Pure White came to be and what impact she hopes it will have on the discussion moving forward. During the course of our conversation we talked about Lady Liberty, White women on January 6th, the Cold War, and what White people absolutely have to understand about Whiteness.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You’ve talked about how some of our national myths are tied to White supremacy and Christian nationalism. Would you talk a little bit about how purity culture and purity as a theology and social policy is inherent to these myths?

Yeah, absolutely. This idea of connecting Christian virtue with national greatness was something very much a part of 19th century Protestantism. As the White middle class grew and became prominent, White Protestants were sort of anointed to be the national leaders in the United States. And as far as virtue goes, the greatest amount of virtue was on the shoulders of White women through the concept of sexual purity, which was part of Victorian gender ideologies. (And of course, it was an ideal, so it had nothing to do with White women’s actual experiences.) But it presumed that White women were dispassionate, were uninterested in sex, and therefore were more virtuous and more moral than men.

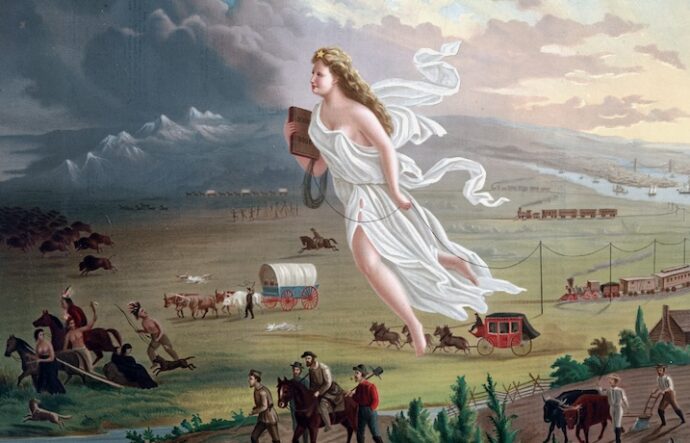

If you go back to the 19th century and look at personifications of the United States, they’re White women. You have Lady Temperance and Lady Liberty. You have John Gast’s [1872 painting, depicted above] “American Progress,” which features Columbia, this White woman drifting from the East coast to the West; behind her the sun is rising, and there are ships, commerce, and men cultivating the land with domesticated animals, while before her are Indigenous people who are being driven off like wild animals. The landscape is dark and forbidding and foreboding.

This was part of a Victorian gender ideology that even White women would come to use in their own political work, asserting that White womanhood is the high-mark of civilization. This is the origin of the myths of innocence I’m looking at, because of course, none of that would work if women weren’t presumed to be sexually pure.

As a teenager I had friends who signed these purity pledges, but it was never really a part of my Catholic experience. It wasn’t until a couple years ago that somebody showed me how purity culture is connected to the social purity movements of the 19th century. For people who are unfamiliar, how is your podcast a way into that history?

Yeah, so we start from the beginning. We start with the True Love Waits pledge and their goals. In 1994, True Love Waits brought around 200,000 pledge carts and displayed them at an event that was co-sponsored with Youth for Christ in Washington DC. They were put on little stakes and tapped into the lawn of the National Mall. So, there’s an image of this lawn with all these cards, and then behind it, the Capitol building, right? So, [my producer] Brad and I actually start with that image. Already the question of White Christian nationalism looms really, really large. Why is this a national issue? Because this wasn’t just about getting more attention, this was about making a political statement.

True Love Waits placed more than 200,000 purity pledges signed by teenagers on the National Mall in 1994. Image: LifeWay Christian Resources

At the time, President Clinton was in office. In fact, during the event, some SBC [Southern Baptist Convention] youth and Richard Ross, who started True Love Waits, met with Clinton, but they weren’t satisfied because they were there to lobby for increased funding for abstinence-only education. Clinton’s response was, “you can’t legislate morality.” Watching archival footage of this event, I was reminded how much evangelicals hated Clinton and how vilified he was despite being an SBC member. [I picture Richard Ross saying] “Hey young people, you’re doing better than your elected president in terms of protecting the nation.” This idea of protecting the nation through sexual purity is Cold War rhetoric. This is stuff that goes back to Billy Graham, and this is part of what I talk about in Virgin Nation, because Billy Graham would say, the communists are going to destroy us unless we get our moral house in order.

But once the Cold War was over, that language still lingered and was picked up by religious groups saying that in order for the United States to be a strong nation, it needs to have a moral core. And that moral core is best defined by evangelical Christian teachings. So, there you have this formula that allows White evangelicals to demonstrate their right to political power: If we don’t have political power, everything’s in trouble.

So again, this is the White Christian nationalism that works, not just on the popular level, but also on the political level—and this has been so firmly ingrained in US political life.

And we’ve already seen the disastrous implications. The overturn of Roe v. Wade was exactly that, as is the anti-trans legislation that’s happening. So, this is about White evangelicals and their allies—Catholics as well. I mean, anyone can be a White Christian nationalist, even though its roots are in Protestantism. Now there’s more allyship politically between religious traditions than within them, so conservative Catholics and conservative evangelicals are working hand in hand.

It’s really fascinating. This podcast is very well timed and important as we witness growing attention on the experiences of those who have been raised in purity culture and on the rise of the Christian Right in the United States. What do you hope will be the impact of this podcast?

I’ve always had a specific audience of people who grew up in and out of purity culture who’ve been following these conversations for so long on social media. I’m looking at what’s missing [from purity culture research and deconstruction]. The focus is always on gender and sexuality, but very few look at sexual purity as a racialized concept. So what I want listeners to understand is that, as we were being formed through evangelical purity culture, it wasn’t just our sexuality, our gender identity that was being formed, it was also our racial identity. And the best way to see this especially is to look at people of color who grew up in White purity culture and how they experienced it.

That’s been my work, trying to understand the racial habits of those of us who were socialized into purity culture, and I think that’s a lesson for lots of people—especially in a moment where we need to be doing a lot more work around White racial identity and understanding its formation. Even though we came into a moment in 2020 of White people thinking about Whiteness and White privilege and White fragility—and I think a lot of that stuff is really good work—if it’s not grounded in an understanding of the historical construction and the political and legal construction of White racial identity, it’s no good because the psychology of it doesn’t just exist out of context. There’s a reason why Whiteness is what it is today. And so, this is my approach to teaching. I think it’s really important for White people to understand the history of Whiteness.

You mentioned there’s this allyship among conservatives across religious traditions, which is something I learned from my research on radical traditionalist Catholicism and its alignment with conservative evangelical Christianity. How do you see this White purity culture and this racialization of purity theology extending beyond evangelicalism?

The myths around White womanhood exist and function in any context, religious or not, so I think it’s important to see the way that, while this was started in a particular religious context, it’s also a national myth. One of the things that I’ve also been trying to understand is January 6th and thinking about White womanhood. So again, regardless of White women’s sexual experiences and their beliefs about it, White women can step into a position of moral correctness simply by asserting their virtue and their innocence. This is the legacy of sexual purity.

When we look at the history of lynching, we see how that exact thing was weaponized to maintain the racial order—that White women’s presumed sexual purity was a way to perpetrate anti-Black mass murder. That is deep in our cultural DNA, these myths of White women’s innocence. That’s what I’ve been looking at—the ways that these innocence myths defeat us and are dangerous. January 6th is an interesting example, the amount of delusion that it takes for people to accept the Big Lie.

You already have a place [the Capitol] where these national myths are coming to the fore and people willing to commit violence. I was really interested then in looking at the White women who were involved. When Ashli Babbitt was killed, I paid attention to the way people responded. And on the Right, she immediately became a martyr and was described as “a girl.” She was described as unarmed, which she wasn’t. She was a military veteran, but she broke the law. She broke through a window and was part of a mob.

So, I started looking at other White women who were part of January 6th, who represented themselves as innocent of wrongdoing or as ignorant of what they were doing so they weren’t responsible. And not only that, but when they went to court, their lawyers also represented them that way. They were presented in relationship to their husbands or people they cared for. And so, therefore, sort of incapable of doing something that on a national level could be a form of treason.

This idea that White women could turn against the nation when White womanhood was constructed to be the national emblem is an internalization of the myth that White women cannot be capable of betraying their nation. And yet, that’s exactly what we saw on January 6th. That’s where both my book and the podcast end.

For those encountering your podcast, people like me who are White women in America, you noted that parts of these discussions are likely to be uncomfortable. What do you hope that White women, but also White Christians as a whole, will take away from Pure White at a time when discussion has increasingly been devoted to the way that Whiteness operates within North American Christianity.

So, I think for people who are in deconstruction mode [i.e., rethinking and often losing their beliefs], whether identifying as former evangelical or ex-vangelical, I think this is a tool for grounding that reflective work within a broader history. I’ve been in groups with evangelicals who are saying, “oh, I don’t want to think about the past anymore. I only want to think about where we’re going.” I knew what they meant was, let’s not dwell on the things that have really harmed us, but as a historian my response is: no, we need to go deeper into the past because that’s where we understand the roots of all of this and where we can really break free of it. I think because we live in the United States where everything is hyper-individualized, we think of ourselves as being ultimately responsible for everything that’s happened to us and we don’t see ourselves as part of broader cultural movements.

So, for people who are deconstructing, I want them to know this isn’t about you failing to live up to a certain set of standards. You were set up to fail. This was a political project that you were a part of because you were born into it, or you were drawn into it. Evangelicalism is so totalizing in terms of belief, in terms of community—so to lose that you lose so much, and so one must grieve. That’s one of the reasons I want people to be gentle with themselves, to listen and take breaks if they need to.

Also, there’s an extended episode on True Love Waits (episode six) focusing on the clergy sex abuse crisis in the Southern Baptist Convention. I read some of the True Love Waits materials, and it’s straight-up victim blaming. No wonder they’re treating the survivors the way they do—because they believe people are making it up. I’ve really struggled with my anger toward the authors. Episode six is difficult if you’re a survivor or sensitive to narratives; that’s one to take very slowly.

For people who are worried, every podcast has a description, so you can know what to expect. When it comes to triggers, it could be so many kinds of things. And when you’re in it to the degree that I have been, you get so numb to it. I do appreciate that people can read this first and get sort of a deeper sense of the topics we’re going to be talking about. This was made for all the Gen X kids—so yeah, it was a little existential.