Cloying sentimentality, saccharine pablum, ridiculous camp and embarrassing kitsch—in the contemporary moment the word “angel” hasn’t fared well among those who describe themselves as sophisticates or intellectuals. To many, angels don’t simply conjure superstitious beliefs, but embarrassing superstitious beliefs. Faith in God doesn’t quite raise as much opprobrium, if only because such beliefs may be recast in more intellectually sophisticated philosophical arrangements.

But for those who affirm that they’re beyond such things, angels would seem to be beyond redemption, and belief in them understood as immature, dim-witted, and déclassé. The sort of subject left to supermarket tabloids like The Weekly World News, which in 1996 breathlessly declared, with tongue only partially in cheek, “Airline Pilot Photographs an Angel!,” between a blurry “photo” and a pull quote informing readers that the “FAA launches top secret investigation into incident.”

To those who dismiss any sort of faith in angels, they belong to a category that also includes ghosts and UFO abductions, clairvoyance and Sasquatch. There are reasons for such dismissals, of course. Many pop cultural representations of angels borrow extensively from Victorian sentimentalism. Such angels are on sale at reduced price; cheap wares for cheap faith.

It would be an error, however, to fully dismiss pop culture angels. Despite the fact that representations of angels in film and television, comics and music, paperback novels and posters, are filtered through market concerns, such pop culture can still speak to human meaning—and because of that they merit our attention. Besides, the bulk of art made in any time period is going to be bad; we’re only aware of all the kitsch produced in our own era because we happen to be witness to its creation.

For every hokey Touched by an Angel episode or Thomas Kincaid painting, there are works which convey a theological significance that’s every bit as pertinent and moving as works that happened to survive from centuries long ago. Valery Rees argues in From Gabriel to Lucifer: A Cultural History of Angels that angelic pop culture serves to foray “into the world of the unseen… [to] serve as a reminder to keep the imaginal world within our vision while we continue to make good use of our rational capacities.”

Indeed if any more respect is given to literary and artistic representations of the demonic than that of the angelic, it’s because the very nature of the former is automatically more engaging to audiences. Easier to render, too. To make great art out of the angelic is its own burden and difficulty, and yet goodness itself is always infinitely interesting in a manner that evil simply isn’t. Perhaps actors enjoy playing villains more, and maybe that says something of human nature, but evil is rapacious and greedy, and thus comprehensible in its own way. Goodness is all the more mysterious by comparison, and more interesting because of it.

Below are a selection of images from Elysium: A Visual History of Angelology which demonstrate the continuing cultural relevance of these most otherworldly beings.

The sheltering wings of Hallmark

A 1997 Hallmark “Get Well” card featuring two angels framing an anodyne non-sectarian prayer is directly traceable to the cult of angelic sentimentality so popular in the Victorian Era. Angels populate greeting cards for Christmas and Easter, baptisms and first communions, confirmations and funerals, as well as for health, as in this example. They’re distinctly non-denominational, non-theological, and in a strange way non-religious, a cipher intending to signify happiness and goodness more than any doctrinal affirmation. That these qualities are associated with Whiteness is telling, if not surprising.

Tabloid angels

Long before so-called “fake news” became a mainstay of internet discourse, and prior to Twitter memes and Reddit threads, the original source of populist disinformation were supermarket checkout tabloids such as the Weekly World News which continue to specialize in outrageous and obviously fake stories of a supernatural bent. That a publication like the Weekly World News printed such clear falsehoods was part of the point; contrary to what some might assume, the popularity of these tabloids can be directly attributed to their tongue-in-cheek entertainment value.

Touched by an angel — every Sunday

At the beginning of the period of prestige TV known as the “Third Golden Age of Television,” when David Lynch was directing Twin Peaks and David Chase was just launching The Sopranos, one of the most popular shows—albeit incredibly distant from being critically acclaimed—was a hokey, family friendly fantasy series Touched by an Angel. With a nine year run from 1994 to 2003, viewers tuned in to the CBS show (appropriately every Sunday) to watch the angel Monica, performed with the requisite degree of Celtic spirituality by Irish actress Roma Downey, intercede in the lives of troubled women and men. In this mission she was joined by her supervisor Tess, played by the Black gospel singer Della Reese. Touched by an Angel played on stereotypes, of both the Irish and African Americans, and it offered a gauzy, feel-good theology that somehow transcended differences between Protestant and Catholic, and yet which fit perfectly into a very American gospel of self-actualization.

At the beginning of the period of prestige TV known as the “Third Golden Age of Television,” when David Lynch was directing Twin Peaks and David Chase was just launching The Sopranos, one of the most popular shows—albeit incredibly distant from being critically acclaimed—was a hokey, family friendly fantasy series Touched by an Angel. With a nine year run from 1994 to 2003, viewers tuned in to the CBS show (appropriately every Sunday) to watch the angel Monica, performed with the requisite degree of Celtic spirituality by Irish actress Roma Downey, intercede in the lives of troubled women and men. In this mission she was joined by her supervisor Tess, played by the Black gospel singer Della Reese. Touched by an Angel played on stereotypes, of both the Irish and African Americans, and it offered a gauzy, feel-good theology that somehow transcended differences between Protestant and Catholic, and yet which fit perfectly into a very American gospel of self-actualization.

Dissipated angel

Playwright Nora Ephron directed the 1996 John Travolta vehicle Michael, in which Mr. Saturday Night Fever himself, his career resuscitated by a starring role in Pulp Fiction, plays the titular archangel. Largely critically panned, Michael presents its antagonist as a drinking, smoking, swearing, overeating slob who (it is Travolta after all) dances. The film’s tagline declares that “He’s an angel, not a saint,” though of course the mythological being was both.

Angel spawn

Among the most audacious and idiosyncratic of twentieth-century comics, the seventy-five issues of DC’s Preacher tell the narrative of Jesse Custer, a Texas minister possessed by a supernatural entity named Genesis born from the intercourse of an angel and a demon. With the assistance of, among others, an ancient Irish vampire named Cassidy who’s not so subtly based on the recently deceased Shane McGowan of the Pogues, Jesse travels across the United States in search of the God who abandoned Heaven. Central to the story is the Saint of Killers, a manifestation of the Angel of Death who works as a bounty hunter, combining elements of both noir and the Western.

An angel gets its wings

No account of twentieth-century pop culture angels could ignore bumbling, simple-minded, lovable Clarence Odbody, the guardian angel to small-town banker George Bailey in Frank Capra’s 1946 Christmas classic It’s a Wonderful Life. Because of how omnipresent Capra’s movie is during the American holiday season it’s easy to ignore how radical (and disturbing) It’s a Wonderful Life can be. Honest, exuberant, and fair-minded, Bailey is contrasted to the maniacal capitalist Mr. Potter, a big banker with whom he’s in direct competition. Clarence only makes his appearance in the final portion of the film as George contemplates suicide on a Christmas Eve, showing the despondent banker a version of reality had he never lived. Far from syrupy, even if “every time a bell rings an angel gets its wings,” It’s a Wonderful Life combines political radicalism and existential despair into a strangely harmonious whole.

Smarmy angel

Kevin Smith’s 1999 fantasy comedy Dogma generated howls of protest from those who felt that the film was generally impious and specifically anti-Catholic, despite the fact that its director was a graduate of New Jersey parochial schools (or maybe because of it). Real life Hollywood best friends Ben Affleck and Matt Damon play Bartleby and Loki, fallen angels who attempt to manipulate a theological loophole in the hopes of returning to Heaven—even if it means the destruction of reality. Several characters gather to prevent this, including Jesus’s last living relative, the secret thirteenth apostle Rufus as played by comedian Chris Rock, and the angel Metatron played with gleeful, smarmy British abandon by Alan Rickman, as featured here.

New age angel

English painter Josephine Wall, best known for her appeal to fans of fantasy writing, often depicts celestial beings, such as in her piece Earth Goddess. From her website, Wall explains that the angel holds the “universe in her wings… [she] gently cradles our precious world, bearing gifts of tranquility, harmony and peace for all.” In compositions such as this there is an obvious fusion of Abrahamic beliefs about angels with New Age goddess worship, an embodiment of the endlessly shifting malleability of the angel as a signifier.

Furious angel

Francis Lawrence’s 2005 Constantine, a film adaptation of Alan Moore’s DC graphic novel Hellblazer, details the work of its titular character, a metaphysical noir detective who lives in a Los Angeles that exists in a space equally with the dimensions of Heaven and Hell. As with Dogma and Good Omens, Constantine engages a certain “bureaucratizing of the sacred,” an understanding of the transcendent realm as reminiscent of the political, social, legal, and economic structures which define our lives. This is, of course, not substantially different from how, during the Middle Ages, Heaven was described as a kingdom. Underrated as a movie, Constantine features Tilda Swinton as the archangel Gabriel, evoking that being’s fury, androgyny, and beauty.

Eroticized angel

Uncomfortable as it is obvious to admit, angels have often been eroticized. The combination of innocence and beauty has made such beings a locus for a particular type of sexual longing the Victoria’s Secret lingerie company leans into with their annual fashion show featuring models who are designated as “angels.” In this 2014 photograph South African model Candice Swanepoel strides the catwalk in glittering, golden wings.

Postmodern angel

With a name almost absurdly appropriate for her subject matter, Doreen Virtue’s Healing with the Angels is an embodiment of a particularly American and supremely postmodern approach to angelology. Post-sectarian, post-denominational, and post-theological, New Age understandings of angels can reduce them to mere therapeutic helpmates, confectionary for the soul.

Cheeky angel

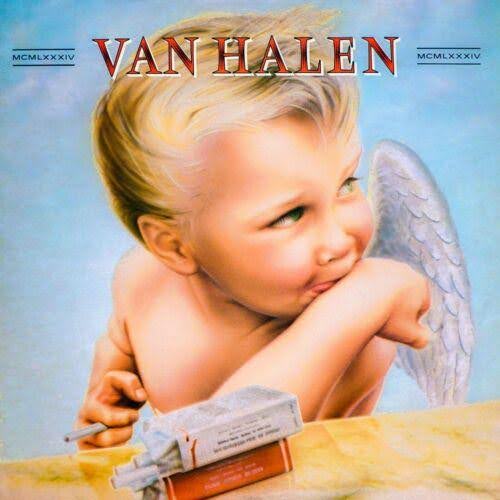

California rockers Van Halen had perfected a particular type of sound that emphasized volume and fun in equal measure, all on ample display in their album MCMLXXXIV released appropriately in 1984. Featuring radio and jukebox friendly hits like “Hot for Teacher” and “Jump,” the album is punctuated with the driving guitar work of Eddie van Halen and the caterwaul vocals of David Lee Roth. Unabashedly anti-pretension, MCMLXXXIV is famed for its irreverent and cheeky album cover featuring an adorable putti with a pack of smokes.

Irreverent angel

Equally storied, but very different from Van Halen, Seattle grunge rockers Nirvana likewise drew upon irreverent angelic imagery to signal a general disdain for mores and the status quo on the cover of their third album, 1993’s In Utero. With edgy tracks like “Heart Shaped Box” and “Rape Me,” In Utero bolstered Nirvana’s reputation as boundary breaking musicians.