When social psychologists Marah Al-Kire and Michael Pasek primed White members of a research panel with an article about anti-Christian bias in America, those participants were more likely to perceive such bias in society. Hardly a surprising result. But follow-up questions revealed a more startling connection: Panelists shown an article on anti-Christian bias also showed increased perceptions of anti-White bias in American society.

When Black panelists were added to the mix, they did not make the same association: “We found White Christians, but not Black Christians, perceived that anti-Christian bias reflected anti-White bias,” Al-Kire tells Religion Dispatches.

Later experiments focused on whether the same connections would be drawn when the message was delivered by a politician. Along with the rest of the research team, Al-Kire and Pasek wondered whether politicians talking about anti-Christian bias would be perceived as “being more concerned about anti-White bias, and also more willing to fight for White people,” according to Al-Kire.

This time both White and Black Christians picked up on the signal, demonstrating that political messages about faith actually communicate something about race.

Al-Kire and Pasek suspect faith-talk is used to convey coded messages that would otherwise be socially unacceptable. “We know that racism is widely condemned,” says Pasek. “We’ve gladly moved past the days where you could have these overt racist actions taking place in the public sphere. And yet we also know that there are a lot of people who still harbor deep racial prejudices.” What Pasek and Al-Kire believe is that talking about threats to faith allows people to discuss threats to their White identity.

Sam Perry, a co-author of the study, situates this finding in the long-standing American tradition of conflating Whiteness with Christianity. “[There’s a claim] that America belongs to people like us, usually meaning Anglo Protestant men,” Perry says, pointing to a dynamic recurring across American history, from early settlers to the Know-Nothing Party of the mid-19th century even up to the present day.

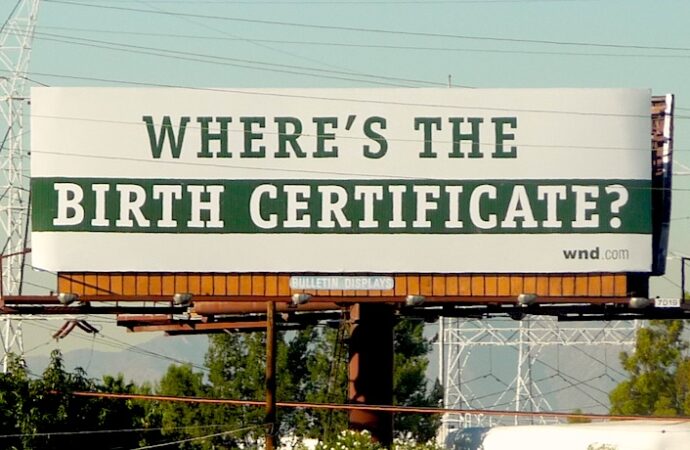

“With the rise of the Tea Party movement, you have a reaction, a backlash to Barack Obama’s presidency, which really seems to be the last straw [for some White Christians],” Perry argues.

Coding White identity as Christian faith, as Obama’s opponents did by insinuating that he was “a secret Muslim” is an effective political strategy. It softens the image of the person delivering the message, according to Pasek. Study participants rated politicians who pledged to stand up to anti-Christian bias as less controversial or offensive than those who pledged to stand up to anti-White bias.

“So the same types of actions, feelings, behaviors, when [expressed] in religious terms become palatable,” says Pasek. And, “if you apply the transitive property,” the same feat can be accomplished by speaking more broadly about religious freedom (rather than Christianity in specific).

Furthermore, because arguments promoting religious freedom are perceived as carrying sublimated racial content, both Al-Kire and Pasek agree that the very same religious freedom arguments may be discounted when they’re deployed by more liberal Christians outside of that context. “It might mean a totally different thing,” Pasek says. He’s quick to point out that their research hasn’t looked at the idea, but says “It’s a really interesting question. Does who employs the language affect how it’s heard?”

The perceived threat from religious or demographic change doesn’t have to be communicated directly in order to have an impact. Earlier research by Al-Kire and Pasek reveals that when Christians from any racial demographic were informed that Christians would likely become a minority in the US by mid-century, it elicited feelings that their status and their rights as Christians were under attack.

The panelists who expressed those fears in turn demonstrated more support for Christian nationalist beliefs, and for conservative political views (and the politicians who represent them). Al-Kire believes “that also has important implications for how people think and behave, such as their attitudes toward different groups.” People who harbor White Christian nationalist beliefs “might be more prejudiced toward immigrants, or more likely to favor restrictive immigration policies,” for example. Al-Kire says some research has suggested that people with these beliefs might be more prone to “even anti-democratic attitudes and behaviors or support for political violence.”

“Just like racial shifts lead to racial threat” to social status, “religious shifts lead to religious threat,” Pasek adds. In other words, demographic changes can lead to the perception that “Just not being a majority or losing your majority [status] means you’re under attack, like you’re losing your rights.” That fear of loss, he believes, is leading to an embrace of far-right beliefs and prejudice.

Perry suggests these perceptions of threat are driven by an evangelical mindset that is part politics and part millenarian: “Within the White evangelical subculture, there is already this narrative of persecution that the Left, the liberals, the woke, the Democrats, whoever, is behind this kind of evil kind of opposition that they face.” He believes this helps explain why White evangelicals rally around Trump or other White nationalist politicians. “It’s just more evidence to them that Trump’s sticking up for people like us,” an idea the former president is eager to reinforce.

Al-Kire and Pasek have their own theories. “I think social dominance is really more inherent or more central to Christian nationalism,” says Al-Kire.

Pasek hypothesizes two paths: “You can be a Christian who believes what the gospel says—treat everyone equally, love thy neighbor as thyself—and embrace pluralism,” he says. “Or you can be a Christian who says, it’s about defending the in-group. It’s about fending off threats.” That perception of threat, according to Pasek, is “very tied up with right-wing authoritarianism, and it’s highly associated with a social dominance group-based way of thinking.”

Both Al-Kire and Pasek stress the importance of understanding religion not just as beliefs, but as identity. Al-Kire points out that sublimating racial discourse in faith language is common in political rhetoric. “It’s not just about religion,” she says. “It’s indirectly communicating concerns about White people and allegiance along White racial lines too.”

“Religion is much more than the way that we tend to talk about it,” Pasek argues. “It is a potent identity that’s a major force in our politics and our social fabric,” he says. “We go to church or synagogue or mosque and it provides us belonging.” But at the same time religious identity has a darker side: “It opens us up to manipulation because identity can be easily used to tear us apart by those who want to use it in that way.”

Still, faith is not inherently discriminatory, the researchers say. Al-Kire recalls earlier studies demonstrating that self-reported religiosity in general was positively associated with perceptions of immigrants, while adherence to Christian nationalist beliefs in particular had the opposite effect. “Christian nationalism is religion co-opted for political ends,” she says.

Pasek has had similar experiences. In his research, asking subjects to make judgments about people outside their group tends to lead to discrimination. “But when we ask people to think about God, it ends up leading to more prosocial attitudes, more benevolence across group lines.”

That might sound like a positive endorsement of faith, but Pasek’s argument is that religion is prosocial or antisocial depending on how it’s presented and who’s doing it. “We want to make clear that faith has so much good to play in society,” he says. “But it shouldn’t be merged with social dominance, groupishness, and exclusion. That’s really where the risks come in.”