Soul by Soul: The Evangelical Mission to Spread the Gospel to Muslims

Adriana Carranca

Columbia Global Reports

April 30, 2024

But Carranca situates this narrative in a larger story of missionary evangelism—dominated, but not necessarily controlled, by American organizations and funding—that sends missionaries from the Global South around the world, bringing with them right-wing ideology with roots in the US.

That story caught the attention of Religion Dispatches Senior Writer Daniel Schultz, who spoke with Carranca about the politics and money of spreading the good news, from a post-Civil War influx of Confederates to Brazil to crusades against the beast of communism to the emergence of a new beast in need of conversion: Muslims.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us about this network of missionaries, which, as I understand it, sort of flows from the US into Latin America and out across the world?

Brazil at first received a few missionaries. There were some Presbyterians from the American Board of Missions in 1859—but very few. Then [after the US Civil War] you had a wave of Confederates. That was a huge influence. They were the first ones who built churches because they came to live in Brazil [permanently]. So they had to have churches and Christian schools.

So when the missionary global efforts of the US evangelicals really began to take off, the structure was [already] there in Brazil, many churches and Christian schools and all that, and pastors who spoke Portuguese. They, of course, started converting locals.

Evangelical Christianity in Brazil, as in other parts of Latin America, grew [and] became really similar to US evangelical culture. It’s really because of [these US missionaries] that evangelical culture became a major religion in Brazil. It’s growing and about to become, possibly by 2030, larger than Catholicism.

Is there a political element in the current network driving this missionary work?

Evangelicals have no central figure and they’ve multiplied into hundreds of thousands of small churches, all independent. You don’t need to be educated to become a pastor. So they grew in Brazil, [in the rest of] Latin America, and in Africa—everywhere—kind of in this crazy way and they’re all very independent. So it’s hard to track the money.

For example, Luis is an independent. I spent 10 years following him and I knew that he would have money for food [one day] and another day he would not, because someone in the church didn’t send the money. The money was not like a fixed salary for him.

If I understand what you’re saying about the funding in this movement, it evolved in a highly decentralized way. The intention wasn’t necessarily to make it difficult to track, but that sure is the end result.

Each organization can send its missionaries to preach the Gospel domestically or overseas. The money for the mission can come from church savings, donations from churchgoers, family and friends, or public funds (e.g., government contracts to provide a particular service such as refugee settlements, emergency relief, aid, and so on). As I mention in the book, Christian faith-based organizations have received USAID grants to operate in Muslim countries, even though some of them have a clear proselytizing agenda.

With the globalization of evangelical Protestant Christianity, money can flow from anywhere to everywhere. For example, I interviewed a Brazilian independent missionary in Afghanistan supported by US donors through a church in Iran. Luis was supported by donations from fellow churchgoers and family members in Brazil, an American friend, a Scottish pastor, and a private pizza-delivery business he opened in Kabul, Afghanistan to help finance the mission. You have multiple sources in different countries supporting missionaries today.

So the mission is funded in different ways, but the money behind it is really [given for] the training and equipping of pastors.

All these huge conferences started to gather these global bodies together and gave them a sense of [being] one church. But what’s behind the modern global evangelical movement, which kind of started with the Lausanne movement in 1974, was the strategy behind it. That’s seen as a turning point in the global movement where Billy Graham wants to bring everyone under his tent, not only in America, but abroad. He started traveling during the Cold War. So there was a [clear] political goal to that.

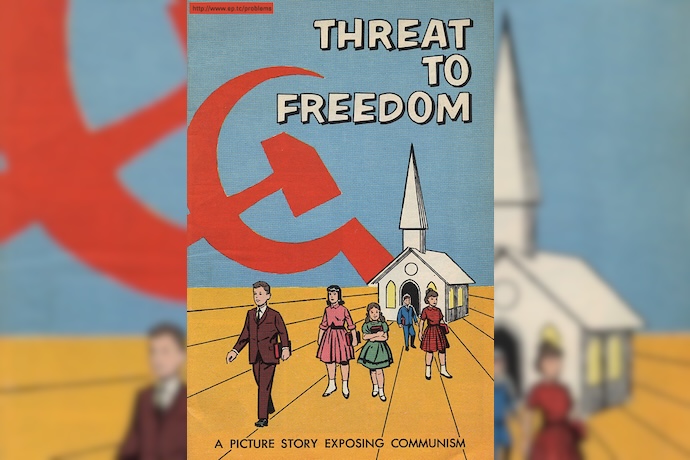

Billy Graham was the best anti-communist spokesperson abroad during the Cold War. After World War II, they started seeing that they could reach the world, not just America. [And] not only with religion, but also with the political anti-communist, right-wing aspect of it.

I’m struck by what you’re saying here. Americans tend to worry about hidden Christian nationalism, yet if what you say is true, one of the biggest threats is and always has been out in the open.

Graham framed the Cold War as the end-times final battle of Armageddon, good versus evil. “Either communism must die, or Christianity must die,” because it is “a battle to the death,” he famously stated. And he would preach things like “If you would be a true patriot or a loyal American, then become a loyal Christian.” From the point of view of the US government, [this] religious revival couldn’t be timelier.

Then he took his crusades worldwide. Between 1962 and 1974, Graham personally met the region’s most brutal anti-communist military rulers, including Fulgencio Batista of Cuba, Ernesto Geisel of Brazil, Alfredo Stroessner of Paraguay, and Augusto Pinochet of Chile, whom Graham praised as a “great Christian leader.”

Graham wasn’t the only American preacher to wage an anti-communist spiritual fight abroad. During the Cold War, the US viewed the Latin American Catholics’ Left turn after Vatican II as a threat. The backlash included CIA covert operations and the funding of conservative alternatives, including American evangelical missions and preachers.

However, this anti-communist, nationalist agenda was never uncontested. Graham, particularly, was increasingly challenged to come out against the evils of the time, including racism in the United States, the Vietnam War, apartheid, and the brutal military regimes in South America.

Graham was also aware that the future of the Christian faith was no longer in America. In the 1970s, the gravity center of Christianity began shifting from the Northern Hemisphere to the South with the explosion of Pentecostalism in Latin America and Africa.

Read Anthea Butler’s BILLY GRAHAM AND THE GOSPEL OF AMERICAN NATIONALISTIC CHRISTIANITY

So the encounters between evangelicals North and South reshaped the movement and the future of Christianity. Evangelicals are still almost homogeneously conservative, anti-abortion, and anti-LGBTQ+ rights advocates. But they have also developed into a diverse, multiethnic, multicultural, economically, and generationally diverse global Christian family whose perceptions of the world differ.

In Latin America, there was a very strong evangelical Left that was born together with the Catholic Left in Brazil that was simply crushed. Billy Graham and leaders like him [vocally] supported military regimes in South America, the right-wing dictatorships. They related to the communists as the beast, as evil. Then after the fall of the Berlin Wall, communists were replaced by Muslims.

If you remember, the first [terrorist] attacks in Africa were around the 90s. Right after the Cold War, you had al-Qaeda’s first attacks on US bases in Africa. Then in 1993, the attack at the World Trade Center that failed. The beast, the evil, became the Muslims and this whole movement turned east to convert them.

When September 11th happened, they just saw that as a huge opportunity because, they thought, Muslims are going to be outraged by what was done in the name of their religion. So…we might have an opportunity there to convert. But by 2002 many American missionaries started to be targeted in Muslim lands. Then they figured out they had this army of Latin American believers who could go, who were ready.

Luis Bush, the Argentinian mastermind behind the 10-40 window [the area between 10 and 40 degrees north of the equator with political and socioeconomic conditions thought to favor evangelism], would say It was as if God had led us to prepare Latin America for exactly that moment. We could no longer send Americans, so let’s send Latin Americans.

I want to send us out with some focus here on rising Christian nationalism, both in the US and in Brazil. Given that context, what do you think American readers need to know about this missionary movement?

There is this well-financed wave of pastors and missionaries with a very right-wing neo-evangelical perspective, who have started new churches. Evangelicals became the largest supporters of Bolsonaro in Brazil and Trump here in the US. One of Bolsonaro’s ministers was part of an organization [launched] to influence the Supreme Court, just like [the Federalist Society] in the US—to fight for anti-abortion laws and all that. She was a minister, and this was supported by the US as well.

But that relationship of right-wing Bolsonaro supporters and Trump supporters began back in the 1970s [during Brazil’s dictatorship]. Those groups, who today form the base for Bolsonaro and Trump among evangelicals, came from those transnational relations that were formed against communism in the 70s. The dictatorship with the clear support of the US urged these churches and charities to go to dictatorships in Latin America to influence and take believers from the Catholics. [The goal was to] just win souls—more to right-wing politics than to Protestantism.