On August 1, NASA’s Pheonix Lander, parked for the past few months on the north pole of Mars, collected a soil sample with its robotic arm. The soil was then transferred to a heating device that scientists call “the oven.” When heated, the ice in the soil melted, producing water vapor. Scientists at the University of Arizona thus confirmed what had long been suspected: that water, and not carbon ice, existed on Mars. The scientists’ report ended with a flourish: the Pheonix Lander had “touched and tasted water on Mars,” it read. Champagne corks popped. Google changed its logo to a Martian theme. The phrase “origins of life” was heard all over the network news.

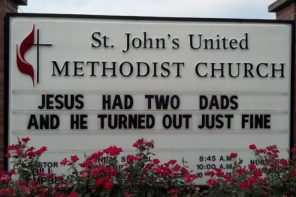

Indeed, the tale is almost Biblical: the people send out scouts to the foreign territory—remote, inaccessible, and rumored for years to hold bizarre forms of life. The spies return with reports of the soil, the landscape, the colors, even the possibility of habitation. Such was the story of Moses sending spies into the land of Canaan in the Book of Numbers. So also is the story of the Pheonix after landing on Mars—except that the scouts are mechanical scoops operated by computer in a landing module. And the reports are not told in person to a band of wanderers in a desert, but beamed back by satellite to scientists in a lab in Pheonix Arizona.

The religious overtones of exploration have been with us ever since humans have been exploring. Plunder and domination, two of the more well known motives of explorers, have existed side by side with the deep sense that there is a transcendent sanction for the journey. According to legend, Phoenician explorers called the new land they discovered “Barr Ilu,” “The Continent of God.” The pilgrims coming from England via Leiden, were indeed that—religious pilgrims who longed for a new world in which they could imagine a society without religious persecution. The discovery of water on Mars is a moment in which we can imagine afresh the origins of life.

On the one hand, exploration is one of the most mysterious and moving activities that humans can undertake. We know of the religious conversions of astronauts after their space journeys. We know of one astronaut’s search to find the Ark here on earth. We know of their renewed and deeply spiritual commitment to public service. And those of us who were around for it remember with great reverence and emotion of that night in July of 1969 when human beings first landed on the moon. Exploration is what some theologians and philosophers call a “limit experience”—an experience at the outer boundaries of daily, “normal” human life. It is almost always mysterious; typically marks a moment of major change; and it almost always gives shape and definition to life following it in which time can be measured as coming “before” and “after” that moment. The exploration of Mars, too, is a “limit” experience for the watching world.

But exploration cannot help but turn into domination, as a “visit” between cordial strangers becomes a “settlement” and then a “society.” The so-called “Age of Exploration” led quickly to the age of colonization and missionary zeal—first of the Catholic, and then of the Protestant churches of Europe. Trade relationships based on mutually beneficial difference gave way to competition for land and resources, which gave way to violence and expulsion. The United States would not have undertook the plunder and domination of the native peoples of North America without the profoundly religious understanding that our “destiny” was manifest—that settlers had the transparent and god-given mandate to explore and take possession. “No condos on Mars yet,” quipped the MSNBC news reporter interviewing one scientist, “yet being the operative word.” The twenty-first century “Age of Exploration” means that reports of “touching and tasting” water on Mars turns immediately to talk of condos on the planet.

Much of the religious sanction for exploration and settlement was premised on the idea that the resources and wealth to be garnered was boundless. And yet the discovery of water on Mars comes at another time of limits, though in a very different sense than before. Human beings are coming to know the limit of natural resources that once seemed endless—including water. Some scientists predict that the earth’s natural resources of oil will be completely exhausted in perhaps as little as fifty years. Competition for water as a productive resource is more intense than ever before—and the list goes on. Because of this different “limit experience”—the knowledge that we are indeed limited—the hunt for renewable forms of energy has reached global dimensions.

At this particular historical moment of energy scarcity, we should seize the opportunity to treat Mars in a rather different way than we have treated the other worlds we humans have “discovered“ thus far; not as resources to be plundered as if they were endless, but rather as finite resources to be conserved and protected with care. There is, thankfully, time for Mars as scientists have yet to confirm the presence of organic materials, the building blocks of life, in the Martian soil. If they’re lucky, says Dr. Jim Zimbelman of the National Air and Space Museum, they will find single cell bacteria. And further “missions” to Mars will be years in the making.

Explorations are indeed mysterious, and touched with the transcendent—definitive proof of water on Mars is no exception. But it might also teach us a new definition of the transcendent. Perhaps we might even call our discoveries sacred as we realize that what we discover is precious and finite, and not infinitely available for our consumption and disposal.