August 16, 2008, was the thirty-first anniversary of Elvis Presley’s death, though some still to this day wonder if perhaps the King lives among us, undetected but free from the prisons that were surrounding him as his popularity soared, crashed, and burned. Dead or not dead, this year’s anniversary for Elvis, like years past, will include vigils and markets, testimonials and memorabilia, pilgrims and consumers, and other cultural evidence signaling spiritual fecundity as much as commercial vitality. Elvis Presley Enterprises grand celebration of the week leading up to the death day, christened Elvis week, raises the perplexing question of how best to acknowledge the religious significance of the sacred dead King?

One place to begin is with a fact: Elvis Presley was not black. But the black roots of the music he helped popularize – and the popular, material, religious cultures that blossomed for millions of Americans from the end of the 1950s, which still flourishes today because of the music – is difficult to deny. For this very reason, Elvis is also an inflammatory icon of real-life white racism and cultural exploitation to some rappers, his product a profanation of African American musical traditions. As Public Enemy’s Chuck D sings in “Fight The Power” (which first appeared on the Do the Right Thing soundtrack, Spike Lee’s 1989 meditation on racism in America): “Elvis didn’t mean shit to me.”

Elvis didn’t cause a cultural revolution solely because of his encounters with and formation by African American cultures while growing up in Tupelo, Mississippi, and later in Memphis. He was something of a musical sponge, absorbing a wide range of musical influences including hillbilly, country, rockabilly, and blues, along with the Pentecostal-filtered gospel he learned from his parents as a child.

But the notion of organic assimilation or natural influence does not quite get at the more active power, truly mysterious and inexplicable, that follows the music, emanating from that young, energetic body playing the guitar, singing a tune, and moving above and below the hips to the undeniable rhythms – sexually suggestive, as was most feared at the time, but also potently sacred, too.

More like a trickster or conjurer, to apply African categories, at the dawn of his long, ultimately tragic career, Elvis embodied and performed music that combined available musical repertoires in entirely new, creative, transformative ways that altered realities, generated cultures, and empowered communities. The world is a different place after Elvis, a new world that was forged but not defined by the chaos, conflicts, and crises in the decade following his television appearances in the late 1950s.

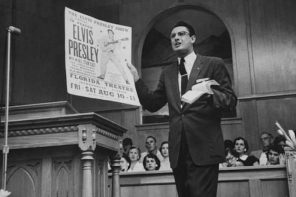

Rock and Roll music did not begin with Elvis, but his performances in these early, seminal years captured the public’s attention enough then and now to remain a valuable mythic touchstone; as part of the sacred story of rock music it acts as a collective representation that frames and opens up the past in meaningful ways relevant to the present. Especially relevant is the mythic effort to emasculate the sexual energy of the music, as always a destructive source of great concern to many in mainstream America, by filming Elvis without his pelvis, below the waist on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1956. (The effort was only partly a myth, it seems. Footage indicates that while the camera revealed the full Elvis in the second half of the program the camera in the first half was far more demure, remaining high and tight).

The energy deriving from the music, filtered through his body, and radiating to communities of fans in his physical or mediated presence, could ultimately not be shut down or controlled. Denying this, even for one fateful moment, only fueled the popular fires then and now burning for more Elvis. The numerous other television shows and performances of the period in the mid to late 1950s had already given the people what they most wanted, and what some most feared: a full-bodied Elvis possessed by a musical attitude and spirit that was quite different from anything that white, mainstream America had ever seen.

Legendary singer Roy Orbison, for example, states in a 1989 interview that he, “first saw Elvis live in ’54. It was at the Big D Jamboree in Dallas and first thing, he came out and spit on the stage… I didn’t know what to make of it. There was just no reference point in the culture to compare it.”

In the immortal words of Butch Hancock, a singer and songwriter from Texas who commented on Elvis in the 1950s, and is quoted in Michael Ventura’s essay on the voodoo origins of rock and roll: “Yeah, that was the dance that everybody forgot. It was the dance that was so strong it took an entire civilization to forget. And ten seconds to remember it.”

For many the musical energy, physical abandon, and liberatory potential of participating in this emergent cultural form of expression – that might include spitting, sweating, and gyrating – was infectious and until that moment in history, unthinkable, engendering a social movement that had and still has political muscle on the streets, commercial value in the markets, and sacred power to inspire activities in each for multiple communities of devoted fans.

Elvis lives. Elvis is everywhere. Elvis is a phenomenon unsurpassed in the modern world, comparable to… who to compare? Tupac or Marilyn or Di or Kurt or Jimi or any other figure in human history, save one or two, fall far short. Hyperbole? Perhaps, but the King is undeniably a cultural force that bears economic as well as spiritual fruit, saving and satisfying, entertaining and enlightening the masses with more than charisma or savvy marketing. The cult of Elvis knows no bounds, has no hard and fast boundaries that distinguish it as only an industry, or entertainment; it is worthy of church, but the spirit of Elvis cannot be institutionalized.

From Graceland to cyberspace, the ghost of Elvis haunts and transforms the lives of Americans who have developed a sacred, meaningful bond between themselves and Him. The annual pilgrimage to Memphis coming up soon; the conventions celebrating his music and life; and the holy relics so highly valued by fans give expression to the religious devotions so powerful in the lives of communities in the Southern, Northern, Western, Eastern United States, as well as far, far beyond national borders.

The material and the ethereal mingle in the sacred wake of Elvis in death. Religious traces are present in cultural products and practices that span the globe, inspiring meaningful relations with merchandise and other fans, between a long-dead entertainer and communities enlivened by his ghostly image and familiar spirit. The Elvis born poor in Tupelo, Mississippi in 1935 and who died rich in Graceland in 1977 fades from view with each passing year, each new generation. But that Elvis, the physical man with the guitar and lips, hip-shakes and sideburns, the one embalmed and displayed before crowds and crowds of people congregating around the corpse, is only half man now, less and less significant compared to the spiritual body that, unlike other cherry ghosts that rivet the public’s imagination after death, cloaks his presence as a cultural saint, or perhaps even better in this case: a popular god.

What more is there to say about Elvis? Books, films, websites, documentaries, photographs, insignias, stamps, music, museums, shrines, articles, say it all: Elvis is a cultural institution, a good earner for the Elvis corporation for sure, but also a comforting point of reference amid the onslaught of information in everyday life; iconically familiar, with multiple meanings and emotional resonances that are still magnetic and energizing to many consumers.

His religious status is also obvious: openly discussed across cultures in testimonials and analyses that require the language of the sacred. Elvis as object of devotion is imaginatively endowed with mythical qualities that bring the sacred to mind when contemplating his visage or hearing him sing.

The God above may or may not be a part of the religious equation; a personal God beyond Elvis, transcendent but imminent and present for many Jews, Christians, and Muslims, does not always put the sacred in its place here in this world, nor determine the afterlife of celebrated figures who capture and hold the public’s eye. In the case of Elvis, the sacred does not remain tied to the bible or Koran, nor does it have anything to do with the sayings of Buddha or the Rig Veda, but is instead generated and regenerated by less-disciplined cultural forces and deep-seated human desires at play in his curious, ghostly presence today as a religious phenomena.

Whether Elvis, and the subsequent musical evolution of rock and roll with attendant mutations and variations, can be traced back to Africa and African American cultural forms and inspirations is an interesting question to pursue. God, on the other hand, is not in the linguistic, ritual, or imaginative mix that propelled and animated the music from the middle of the twentieth century to the present for most actors in this story.

Instead, the music itself is the sacred anchor at the bottom of all this fuss, and without God in the mix – or as the “Master Mixer,” to turn a phrase – the ties that bind members of a community together can be easily disentangled from any particular dogma or tradition; but make no mistake, the recorded and live music, musicians and magnetic rock and roll celebrities, lyrics and ritual gatherings in cordoned off musically-transformed spaces, all have the potential to fashion religious cultures that may conflict, or at times coexist, or in some cases smoothly merge, with traditional religious identities.

Rock and roll culture, like hip-hop to some degree, spins out a variety of musical forms and styles that make it supremely difficult to establish one all-encompassing definition or fundamental characteristic. Folk, heavy metal, experimental, punk, psychedelic, alt-country, and many other labels can be bandied about in the rock musical world and each one can generate its own version of a religious culture. On the other hand, religious cultures do not emerge from just any rocker; the sacred does not adhere in and exude forth from the likes of Steppenwolf, REO Speedwagon, Peter Frampton, or Blink 182, no matter how momentarily popular they might be at any given time.

The sacred, however, is an integral element of certain phenomena in the history of rock, found in its origins with Elvis (and subsequently with others) who contributed to revolutionary musical transformations and collectivities of committed fans from here and from abroad, including The Beatles, The Who, The Clash, Uncle Tupelo, and Nirvana.

What are the signs of religious life in rock and roll cultures? How do the music and lyrics contribute to popular religious experiences that reimagine and reconstruct the world, invigorate and reinvigorate social bonds, and stimulate and liberate the body first, and then the soul? A visit to Graceland during death week this year, like any year, provides abundant evidence that religious life and investments do not always finally refer back to a God above or a soul within.

Instead, at least for brief spell for many pilgrims who trek to Memphis in August, Elvis is King, Graceland is a Mecca, and Death is not the end.