No matter who we choose to cast a vote for this week, ultimately we’re not voting for the men running to be president. What we’re really voting for is security. Who we choose reveals what we feel security is all about, whether it’s personal security in the form of money and wealth, or an attempt to use government for a common good and sense of corporate security. Either way, as people of faith, we’re wrong to invest hope for security in the government or any elected official because they will ultimately fail us, no matter how pure their motivations.

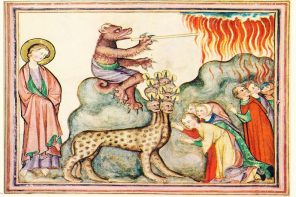

In Luke 4:1-13, we find Jesus facing the temptation of worldly power. He stands on the parapet of the temple in Jerusalem as the devil promises him ultimate security—the angels will catch him. No matter how dire the situation, his security in the world is assured.

German Catholic theologian Eugen Drewermann calls this an “awesome moment” where Jesus, looking at the world’s kingdoms realizes “it is not possible to wield power without serving the devil. I do not see how any political theology can get around that.”

Indeed, we can’t. Whenever we look to the political realm to give us the security that can only come through faith in God, we give in to the devil’s promise that the world has the power to make us safe. We believe that if we just put the right people in charge we’ll be prosperous, happy and secure. It seems to have worked for quite a while. America has enjoyed great wealth, respect, and peace for many years. In prosperous times it’s easy to believe that we can create God’s realm of justice and equity here on earth. But, eventually, things fall apart. Drewermann says it’s to be expected:

The fairest government possible only brings people the return of their old problems, since they will not let themselves be governed like sheep, and the wisest order still does violence to them because they are human beings… It may well be that government is necessary to establish a certain framework of external order; but then all the difficulties of human beings begin again, first and foremost the anxiety they feel in their hearts. The spiral of temptation starts all over.

When that temptation begins we spiral from prosperity to poverty, from peace to war, from sharing to greed. The good times are great, but the anxiety about them ending is overwhelming, and ultimately becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. We seek security in all the wrong places—in our government, in our religious systems, in our economic systems.

In our religions, we tend to concretize our beliefs to assuage our anxiety and seek security. By driving every ounce of mystery out of God and turning our religions into solid creeds about God we can memorize and recite, we, as Drewermann notes “know everything about God because we had managed to avoid God.”

But, Jesus’ goal was to teach us not to trust in governments, markets—or even religions and what they say about God. Instead, Jesus came to teach us how to trust God above anything else in the world. Our religions, however, in their current forms give us no framework for such a goal. In our religious certainty, we learn to trust theologians and creeds and preachers instead of God. As G.K. Chesterton so rightly observed years ago, “The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting. It has been found difficult and left untried.” I doubt Jesus would recognize the religion being practiced in his name today.

Since we cannot find the security we seek in the world and its powerful men and institutions, we so often give in to our anxiety. We want to do good. We want the world to be a just and equitable place. We want the hungry fed, the homeless sheltered and the naked clothed, but we feel helpless to accomplish these goals, individually or corporately—so we give up. We turn on the television and entertain ourselves. We turn to religions full of “we know God” ideas. We vote in elections filled with both hope and trepidation. We care too much and we are overwhelmed.

It is in this caring too much that we commit our greatest sin, according to Drewermann:

I often think that the devil is not the devil but a force with so much compassion for the suffering in this world that we not longer can bear the grandeur of the challenge, no longer can endure this world that we know in all its terror—free, open, unfolding, always in the process of being devoured and bringing itself to new birth. Then the word of God, with all its talk about love, redemption, and trust, begins to be something that turns against human beings and against God.

We want a perfect world and we believe that if we practice all that love and redemption and trust the Bible talks about we’ll get it. When it doesn’t happen, however, we get frustrated. We are impotent to create God’s perfect realm here on earth, so we stop trying. We become cynical—thinking there’s nothing we can do that will truly improve the world. When we arrive at this place, the devil has us right where he wants us. This is when we must remember that God has never promised us a perfect world, but the devil does. When we give in to the devil’s temptation of a perfect world, we give in to the sin of caring too much and in caring too much, we are overwhelmed and stop caring at all. The devil has sealed the deal.

How do we find our way back and repent of the sin of caring too much? We cannot vote our way back. We cannot pass a government bailout to get us back. We cannot create yet another religion of creeds and doctrines to get us back. Instead, we must turn back to the mystery of the God who created us and seek our security there. It’s uncharted territory, but it begins with the promise God made to Abraham in Genesis 12:1-3:

Now the Lord said to Abraham, “Go from your country and your kindred and your father’s house to the land that I will show you. I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you, and make your name great, so that you will be a blessing. I will bless those who bless you, and the one who curses you I will curse; and in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed.”

Instead of looking to earthly things and earthly power to bless us, we are to be a blessing in the world. Instead of caring so much that we become overwhelmed by the wicked ways of the world, we are to live our lives as a blessing to others.

“Indeed,” Drewermann writes, “we have a sacred duty before God to see our lives as a blessing. We must recapture the feeling of being happy and grateful for our existence. We must feel that our existence enriches others, bringing good fortune, joy, and beauty into their lives.”

The good news is we don’t need money, wealth or earthly power to do any of that. We don’t need a presidential decree or a government program or a market initiative or even a social program to accomplish this. When we begin being a blessing to those around us—our friends, our family, our community and, yes, even to those who voted for the other guy—like the shampoo commercial, we begin to see those blessings multiplied.

If instead of committing the sin of caring too much and losing our ability to bless others, we embraced our power to bless others, even our enemies, God will make of us a great nation where all the communities of the earth will find blessing. As you vote on Tuesday, choose the person you think will help us best establish external order, but vote knowing that it is not up to the government, but to each of us to create a secure world filled with blessings.

Quotes are from: Eugen Drewermann’s Dying We Live: Meditations for Lent and Easter. (Orbis Books, Maryknoll, New York, 1994.)