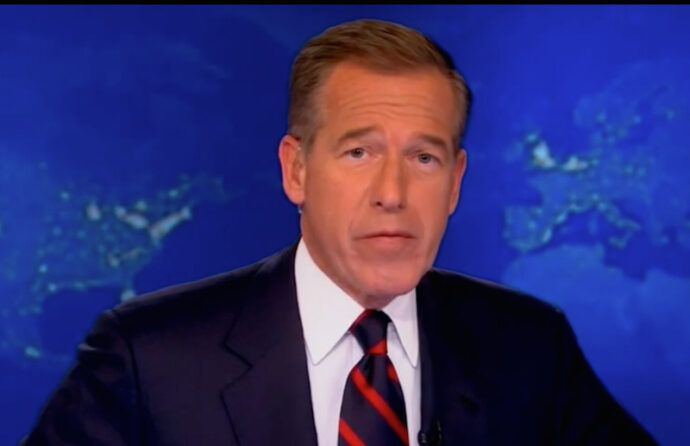

The deafening whomp-whomp-whomp you may have heard when Brian Williams got caught in a lie last week was not the approach of a Black Hawk helicopter. It was the media’s schadenfreude machine roaring to life.

Why would a man at the top of his field risk it all with unnecessary embellishments? Theories filled the air like the flak the news anchor never saw.

In the New York Times, a teaser for columnist Maureen Dowd’s take on the subject mused that Williams fancies himself a scholar-adventurer in the mold of Indiana Jones. At NPR, Berkeley philosopher Alva Noë wondered if the issue here might simply be that “Brian Williams is a storyteller and storytellers can’t resist a good story.” In the New Yorker, Ken Auletta got theological with the suggestion that news anchors “think of themselves as God.”

Yet all this focus on a millionaire newsman’s ego and problematic self-perception obscures the larger issue—the Big Lie of which Williams’ tall tales are but a part.

Williams did not just tell any lie, after all. He told a war story.

He would probably not be enduring such scrutiny had he fibbed about risks faced in any another context. But then exaggerations like those he has made repeatedly over the years seem particularly suited to tales of battle.

To add to the endless exegesis: He told a war story because no matter how unpopular the wars of the last decade became, or how popular they may yet become in popular revisionist memory, to tell the kind of war stories Williams has told is to put oneself at the center of a drama with clear stakes and ultimate significance. War may be hell, but to speak of Americans making war from the pulpit of mass media, one is required to speak of the sacred.

Claiming proximity to this sacred, Williams makes its authority his own. As further examples of his creative memory emerge—from meeting the pope to witnessing the fall of the Berlin Wall—it becomes ever more clear that television news may owe as much to Emile Durkheim as Edward R. Murrow.

At a time when the military receives a reflexive genuflection from every corner of the culture, war stories have become sermons of a sort, and sermons are often untrue. This isn’t so much an accusation as an acknowledgement of the constraints of the genre: Sermons yoke anecdote to larger meaning, things happening now to things that happened in an impossibly distant then. Sermons can’t help but bend facts in the service of supposed truth—a story’s plot and its moral rarely fit so neatly together. And perhaps that’s true of war stories as well.

“For a long time I was angry,” the writer and former Marine Phil Klay notes in his National Book Award winning collection Redeployment. “I didn’t want to talk about Iraq, so I wouldn’t tell anybody I’d been. And if people knew, if they pressed, I’d tell lies.”

Williams’s Icarus-like downfall after attempting to fly too close to the sun of war brought to mind a lie I heard not too long ago told in a pulpit of another kind. Two years ago, a guest preacher visited a church I sometimes attend, and delivered one of the best sermons I’d heard in while. He was likable, eloquent, deeply knowledgeable, and spoke on the need for professional religious types to get out in the world—to the places, he suggested, where true interactions with the sacred might be found.

“I was out in one of the grittier parts of my city,” he said to a congregation of not so gritty older men and women, “and I went into a head shop. You all know what a head shop is right?” They didn’t but boy did they want to.

“There was a young woman working there,” he continued. “She had purple hair and a full sleeve of tribal tattoos. Piercings in places I wouldn’t tell my mama. She sat behind a glass counter filled with silver jewelry. I saw a few crosses in there, so I asked if I could look more closely. ‘Sure,’ she said. Then she asked me, ‘Do you want a plain one, or one with a little man on it?’”

Oh, he had us now. He had been there—to places where even Christ on the cross was unknown, to places just waiting for with-it Christians like him, places that granted the authority of the front lines.

Because I was so taken with the sermon, and because he delivered it with such polish I wondered If he might have published it, I searched the Web for “one with a little man on it” when I got home from church. What I found, of course, were hundreds of variations going back decades, some grittier than others, some likely delivered in far-off pulpits long before he first imagined what it might be like to visit a head shop.

Brian Williams and this fact-challenged preacher are both ministers of a sort—one a Christian, the other a high priest of America’s media-driven civil religion—and no doubt regard their lies as serving a more important truth. Yet the similarity of such lies should call more than the liars into question.

One of the great chroniclers of war, belief, memory, and the deceptions fostered by each, Tim O’Brien (the author of classic Vietnam story collection The Things They Carried), once wrote, “You can tell a true war story by the way it never seems to end.”

If we continue to participate in the lie that war is sacred, our national war story never will.